Thousands of soft-story buildings up and down the West Coast require retrofits to prevent collapse in the event of a major earthquake. Whether the retrofits are mandated by a city ordinance (as in San Francisco, Berkeley and Los Angeles) or are undertaken as voluntary upgrades, the benefits of adding necessary bracing to strengthen the ground story are immense. Simpson Strong-Tie has taken the lead, with our new Soft-Story Retrofit Guide, to provide information that helps engineers find solutions to reinforce soft-story buildings against collapse. We are also providing information on the two methods that can be used for the analysis and design of these soft story retrofits.

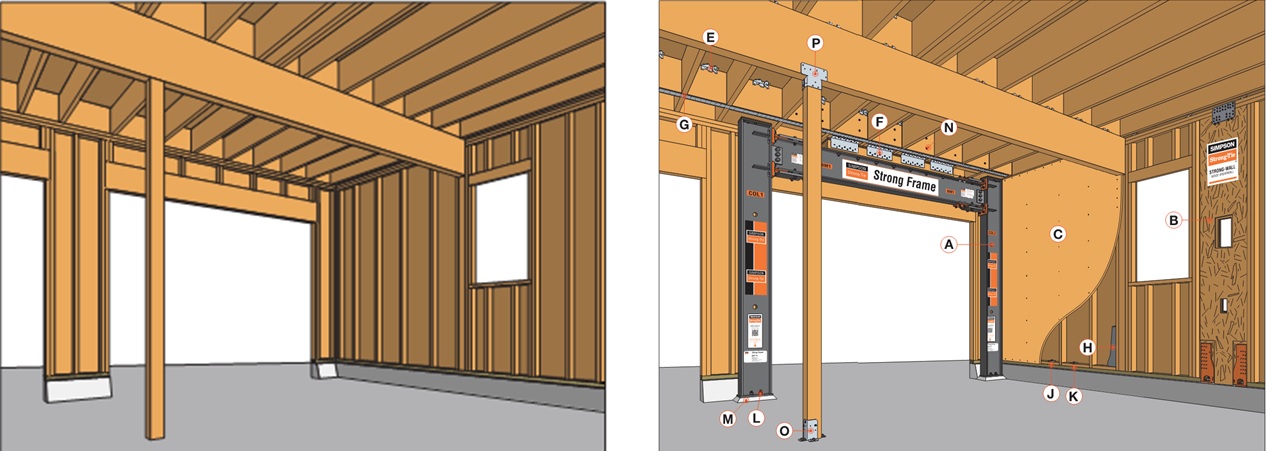

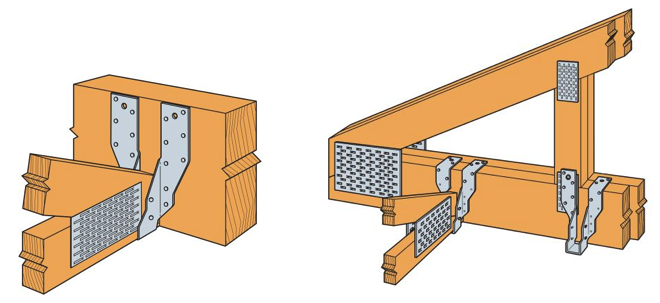

After the initial information section of the guide, a two-page illustrated spread (pp. 14–15) shows various retrofit products that could be used to retrofit the soft-story structure with reference to the following pages. Three main lateral-force-resisting systems highlighted in this graphic are the Strong Frame® special moment frame (SMF), the new Strong-Wall® wood shearwall, and conventional plywood shearwalls. Individual retrofit components are also shown, such as connection plates and straps for lateral-load transfer, anchors for attachment to the foundation, fasteners and additional products such as the RPBZ retrofit post base and AC post caps for providing a positive connection.

After the initial information section of the guide, a two-page illustrated spread (pp. 14–15) shows various retrofit products that could be used to retrofit the soft-story structure with reference to the following pages. Three main lateral-force-resisting systems highlighted in this graphic are the Strong Frame® special moment frame (SMF), the new Strong-Wall® wood shearwall, and conventional plywood shearwalls. Individual retrofit components are also shown, such as connection plates and straps for lateral-load transfer, anchors for attachment to the foundation, fasteners and additional products such as the RPBZ retrofit post base and AC post caps for providing a positive connection.

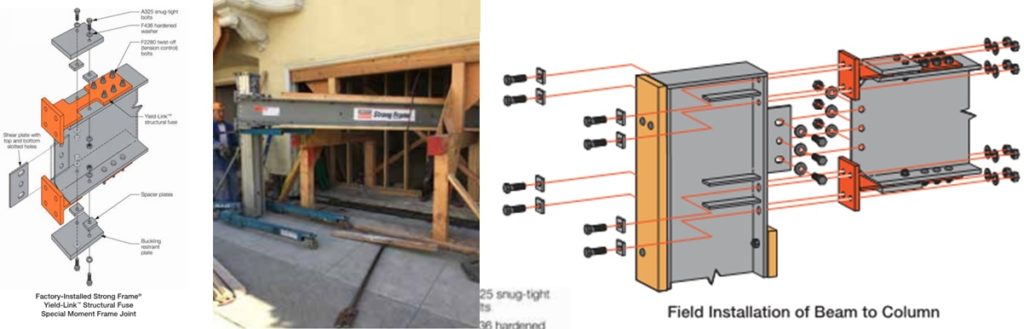

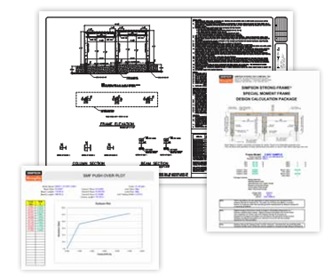

Turning the page, you come to the section describing in detail the many benefits of the Strong-Frame special moment frame (SMF) in a retrofit situation. The engineered performance of the SMF provides the additional strength and ductility that the building requires and can be fine-tuned by selecting various combinations of beams, columns, and Yield-Link® structural fuse sizes. A typical retrofit Strong Frame® SMF comes in three complete pieces allowing for the frame to be installed on the interior of the structure in tight quarters. The frame is simply installed using a 100% snug-tight field-bolted installation with no on-site welding or lateral-beam bracing required.

Turning the page, you come to the section describing in detail the many benefits of the Strong-Frame special moment frame (SMF) in a retrofit situation. The engineered performance of the SMF provides the additional strength and ductility that the building requires and can be fine-tuned by selecting various combinations of beams, columns, and Yield-Link® structural fuse sizes. A typical retrofit Strong Frame® SMF comes in three complete pieces allowing for the frame to be installed on the interior of the structure in tight quarters. The frame is simply installed using a 100% snug-tight field-bolted installation with no on-site welding or lateral-beam bracing required.

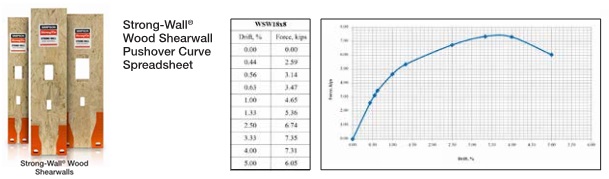

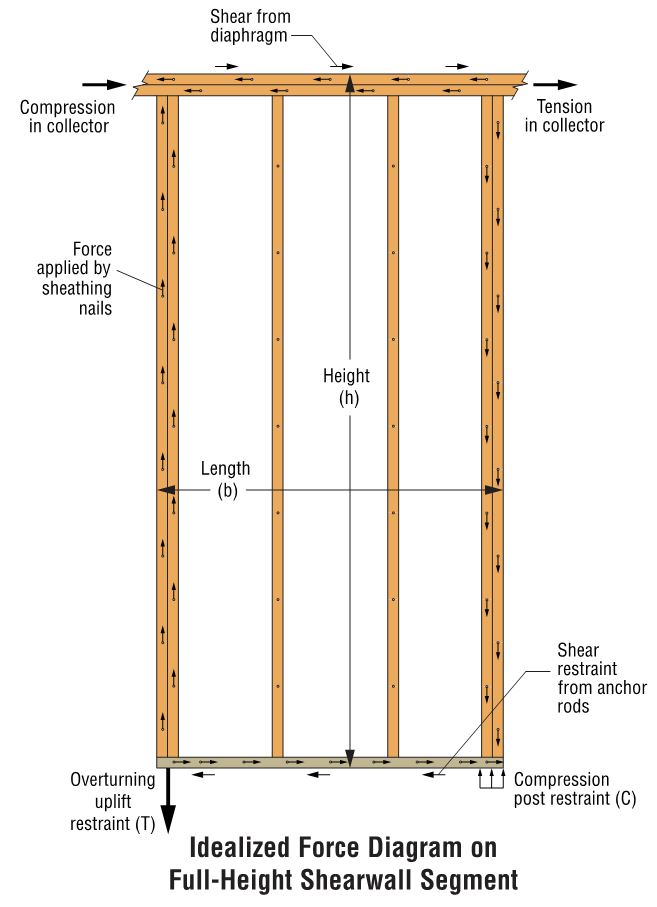

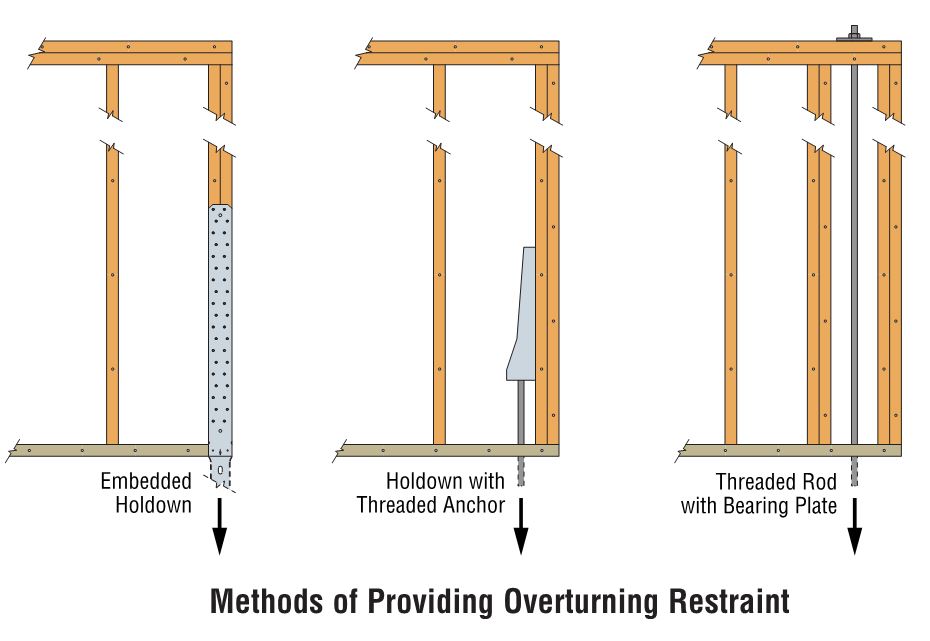

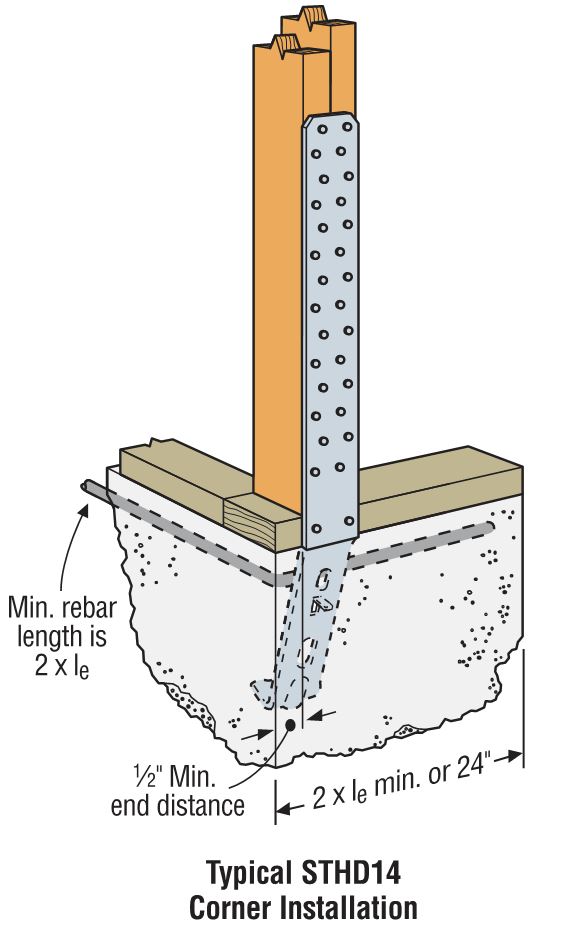

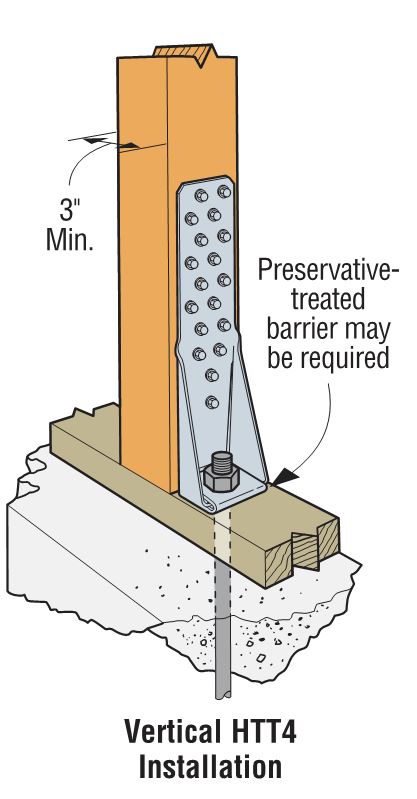

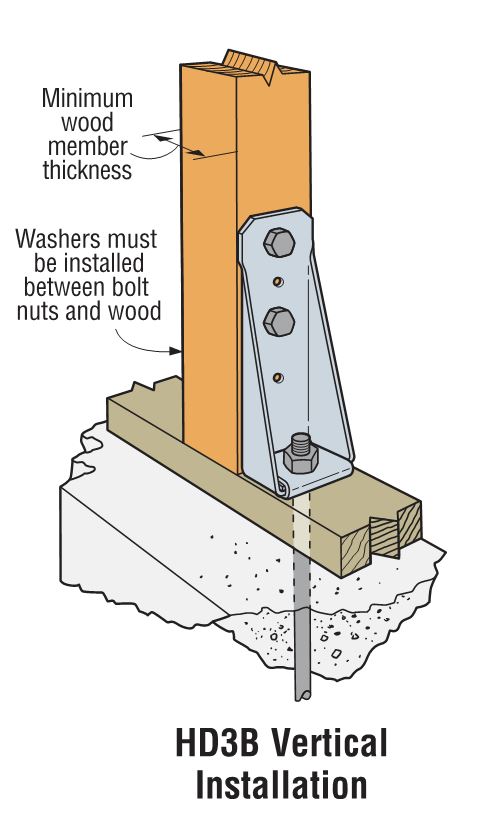

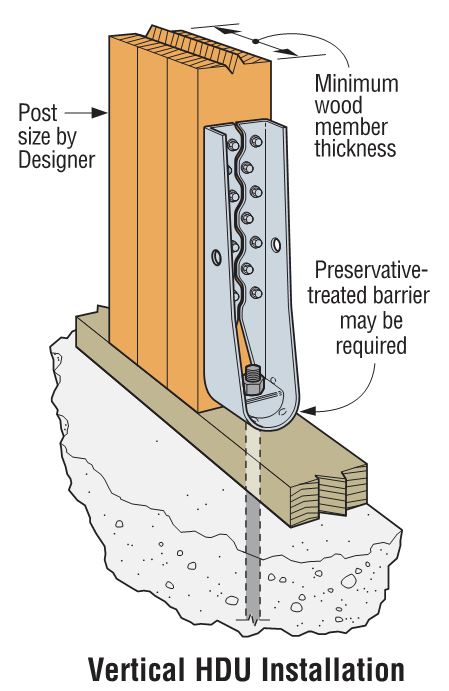

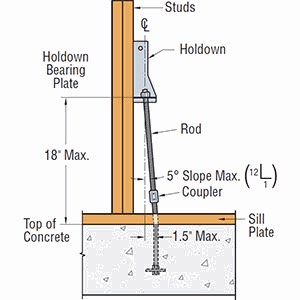

The next lateral system we focus on is the Strong-Wall® shearwall and the new grade beam solutions offered to reduce the concrete footprint. The new Strong-Wall wood shearwall includes an improved front-access holdown and top-of-wall connection plates for easier installation. Both the Strong Frame SMF and the Strong-Wall wood shearwall have load-drift curves available for use with FEMA P-807. Site-built shearwalls can be installed using retrofit anchor bolts at the mudsill and new holdowns at the shearwall end posts.

The next lateral system we focus on is the Strong-Wall® shearwall and the new grade beam solutions offered to reduce the concrete footprint. The new Strong-Wall wood shearwall includes an improved front-access holdown and top-of-wall connection plates for easier installation. Both the Strong Frame SMF and the Strong-Wall wood shearwall have load-drift curves available for use with FEMA P-807. Site-built shearwalls can be installed using retrofit anchor bolts at the mudsill and new holdowns at the shearwall end posts.

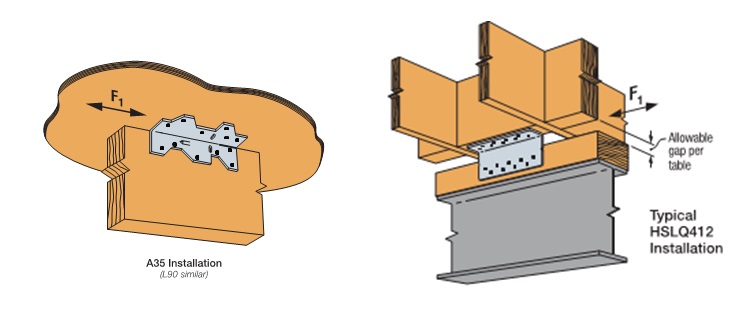

In the pages following the lateral systems, various products are shown with tabulated LRFD capacities, whereas ASD capacities are typically provided in the order literature for these products. Both ASD and LRFD capacities have been provided for products with new testing values such as the A35 and L90 angles installed with ⅝”-long SPAX screws into three different common floor sheathing materials, as well as for the new HSLQ heavy-shear transfer angle designed to transfer higher lateral forces directly from 4x blocking to the 4x nailer on the Strong-Frame SMF, even when a shim is used between the floor system and the frame. LRFD capacities are provided in this new Soft-Story Retrofit Guide specifically for use with the FEMA P-807 design methodology. This methodology specifies in section 6.5.1 that:

In the pages following the lateral systems, various products are shown with tabulated LRFD capacities, whereas ASD capacities are typically provided in the order literature for these products. Both ASD and LRFD capacities have been provided for products with new testing values such as the A35 and L90 angles installed with ⅝”-long SPAX screws into three different common floor sheathing materials, as well as for the new HSLQ heavy-shear transfer angle designed to transfer higher lateral forces directly from 4x blocking to the 4x nailer on the Strong-Frame SMF, even when a shim is used between the floor system and the frame. LRFD capacities are provided in this new Soft-Story Retrofit Guide specifically for use with the FEMA P-807 design methodology. This methodology specifies in section 6.5.1 that:

Load path elements should be designed to develop the full strength and the intended mechanism of the principal wall or frame elements. Therefore, to ensure reliability, appropriate strength reduction factors should be applied to the ultimate strengths of load path elements. Specific criteria may be derived from principles of capacity design or from other codes or standards, such as ASCE/SEI 41 or building code provisions involving the overstrength factor, Ωo.

FEMA P-807 bases the capacity of the retrofit elements on the peak strength. LRFD capacities are provided for various load-path connector products, which can be used to develop the full strength of the lateral-force-resisting element to satisfy this requirement.

Wrapping up, the guide focuses on the various free design tools and resources available for the evaluation, design and detailing of the soft-story structure retrofit. These tools include the Weak Story Tool with Simpson Strong-Tie® Strong Frame® Moment Frames, Design Tutorials for the WST for both San Francisco– and Los Angeles–style buildings, our Soft-Story Retrofit Training Course offering CEUs, Strong Frame Moment Frame Selector Software, Anchor Designer™ Software for ACI 318, ETAG and CSA, and tailored frame solutions using our free engineering services.

Wrapping up, the guide focuses on the various free design tools and resources available for the evaluation, design and detailing of the soft-story structure retrofit. These tools include the Weak Story Tool with Simpson Strong-Tie® Strong Frame® Moment Frames, Design Tutorials for the WST for both San Francisco– and Los Angeles–style buildings, our Soft-Story Retrofit Training Course offering CEUs, Strong Frame Moment Frame Selector Software, Anchor Designer™ Software for ACI 318, ETAG and CSA, and tailored frame solutions using our free engineering services.

For other information regarding soft-story retrofits, refer to previous blogs in “Soft-Story Retrofits,” “City of San Francisco Implements Soft-Story Retrofit Ordinance,” and “Applying new FEMA P-807 Weak Story Tool to Soft-Story Retrofit.”

For other information regarding soft-story retrofits, refer to previous blogs in “Soft-Story Retrofits,” “City of San Francisco Implements Soft-Story Retrofit Ordinance,” and “Applying new FEMA P-807 Weak Story Tool to Soft-Story Retrofit.”

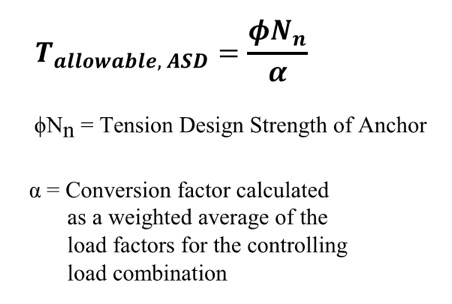

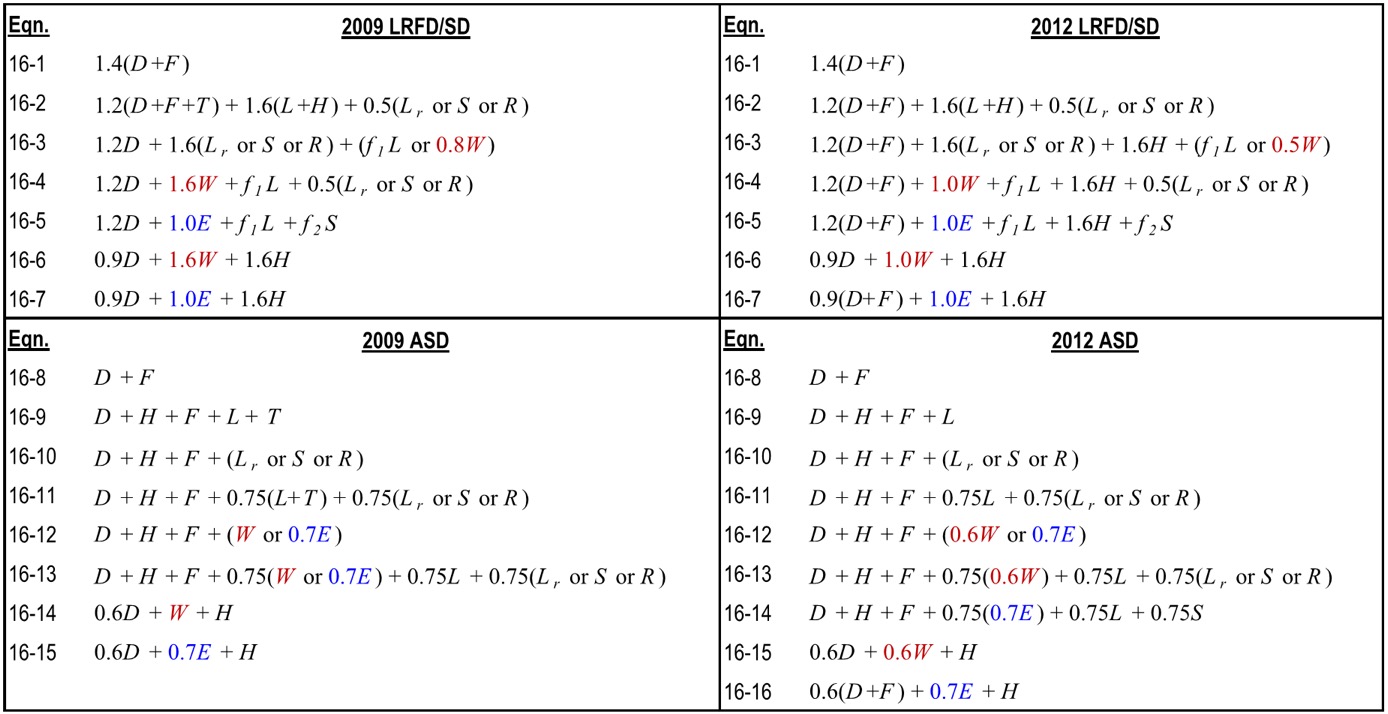

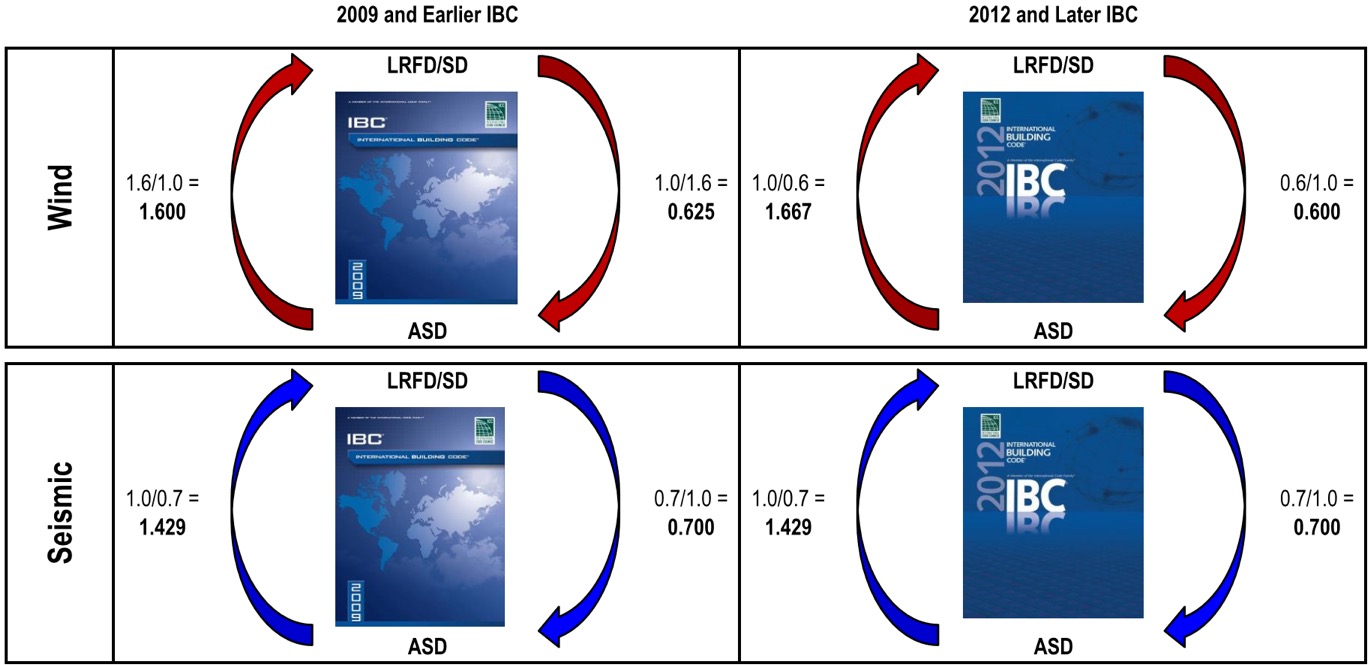

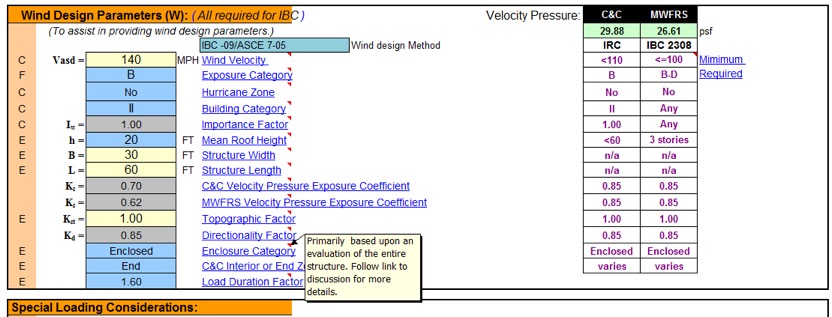

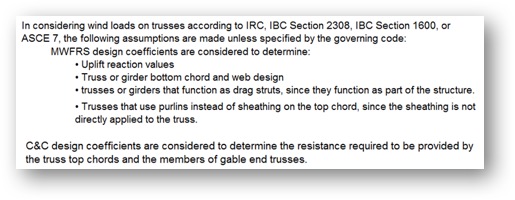

So what do you do now? Well, there is some guidance provided by ICC-ES for manufacturers to convert calculated SD capacities to ASD allowable load values. Since there is no conversion procedure stated in the IBC or referenced standards, designers may want to use this generally accepted method for converting anchor capacities designed using ACI 318. ICC-ES acceptance criteria for post-installed mechanical and adhesive anchors (AC193 and AC308) and cast-in-place steel connectors and proprietary bolts (AC398 and AC399) outline a procedure to convert LRFD capacities to ASD using a weighted average for the governing LRFD/SD load combination. So if the governing load combination for this anchor was 1.2D + 1.6L and the dead load was 1,000 pounds and the live load was 4,000, then the conversion factor would be (1.2)(0.2) + (1.6)(0.8) = 1.52 (keep in mind that the LRFD/SD capacity is divided by the conversion factor in the ICC-ES equation shown here for tension).

So what do you do now? Well, there is some guidance provided by ICC-ES for manufacturers to convert calculated SD capacities to ASD allowable load values. Since there is no conversion procedure stated in the IBC or referenced standards, designers may want to use this generally accepted method for converting anchor capacities designed using ACI 318. ICC-ES acceptance criteria for post-installed mechanical and adhesive anchors (AC193 and AC308) and cast-in-place steel connectors and proprietary bolts (AC398 and AC399) outline a procedure to convert LRFD capacities to ASD using a weighted average for the governing LRFD/SD load combination. So if the governing load combination for this anchor was 1.2D + 1.6L and the dead load was 1,000 pounds and the live load was 4,000, then the conversion factor would be (1.2)(0.2) + (1.6)(0.8) = 1.52 (keep in mind that the LRFD/SD capacity is divided by the conversion factor in the ICC-ES equation shown here for tension).

There are products used in every building not referenced by the codes or standards.

There are products used in every building not referenced by the codes or standards.

limitations.

limitations.