I attended a CFSEI and Steel Framing Alliance webinar last week entitled Specifying Cold-Formed Steel: Finding and Avoiding Pitfalls in Structural General Notes and Architectural Specifications. The presenter was Don Allen, P.E., from DSi Engineering, LLC, and he focused on issues specifically related to design and specification of cold-formed steel (CFS) in contract documents.

The first post I ever wrote for this blog was But I Don’t Design Cold-Formed Steel… I talked about how limited my initial experience was with cold-formed steel and how I was forced to learn it on the job when projects required it. During the webinar, I winced a few times recalling my first CFS project when Don mentioned why you should not do certain things — and they were things I used to do.

Referencing the “most current edition” of a standard was something I remember doing in our general notes, and the webinar mentioned why it is important to verify that specified reference standards are correct for the governing building code for the project. I first designed under the 1994 Uniform Building Code, and then used the 1997 UBC for many years after that. The Uniform Building Code was almost self-contained in that it covered gravity, seismic, and wind load requirements in Chapter 16, and then each of the material chapters had most of the design requirements in the code.

A significant change in the International Building Codes has been removing many of the design requirements and simply referencing the appropriate design standards. Whereas the UBC had methods for calculating wind loads, the IBC simply refers you to ASCE 7 for wind loads. Similarly, Chapter 19 of the 1997 UBC had many pages of concrete design requirements. Now, the 2012 IBC has just a few pages referencing ACI 318 and then makes several amendments to it.

What does this mean for designers? Painfully, it means we have to buy a lot more books each time the code changes. Ouch!

More critical to our designs, however, is we need to be certain we are using the correct reference standards with the applicable building code. One prominent example is ASCE 7 wind loads. ASCE 7-05 calculated wind loads at an allowable stress level, but ASCE 7-10 wind loads are determined at strength level and the wind speed maps are different. The American Wood Council has a good paper on the topic here.

The load combinations in the 2012 IBC were adjusted to compensate for the differences in wind speed calculation, resulting in design pressures that are similar. However, if you used ASCE 7-05 wind loads with the 2012 IBC load combinations, the design would be wrong. Similar conflicts can occur when mixing new (or older) IBC codes with older (or newer) reference standards for steel, concrete, or masonry.

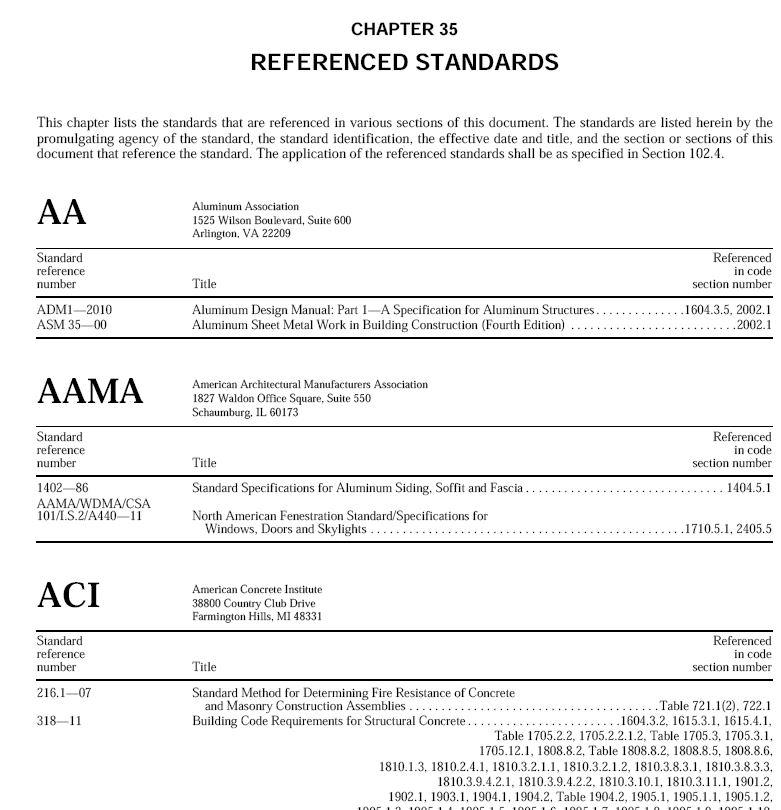

Fortunately, Chapter 35 of the IBC has an exhaustive list of reference standards that are applicable to the code in question.

The webinar reinforced for me how important it is to keep track of where we are designing and what code is in effect, and which of the dozens of reference standards are referenced in that code.

What are your thoughts? Visit the blog and leave a comment!

Thank you for referencing the webinar – it sounds like you got something out of it. I really appreciate the support and products that Simpson Strong-Tie provides for the framing industry: both cold-formed steel and wood.