Take two trusses with identical profiles and environmental surroundings, and they should have the same design loads, right? Early in my career, I recall hearing a story about two identical buildings right next to each other that were designed for two different magnitudes of environmental loads. I remember wondering – how do the loads know which building is which?

There used to be a time when it was not uncommon for 5 substantially different wood truss designs to come from 5 different companies – all designing to the exact same spec. Whereas some differences are always to be expected (manufacturer-specific plate design values and proprietary analogues come to mind), the truss design disparities that used to exist from one company to the next were compounded by variations in something which really shouldn’t vary at all – the application of the specified loads to the truss. Differences in loading can occur whenever there is room for interpretation. In cases where the loading specs for fabricated wood trusses are not very detailed, there is a lot of room for interpretation. And when that happens, everyone knows how many different answers you get when you ask 5 different engineers!

Fortunately, the truss industry has come a long way in this area. In some cases, the codes and standards that govern the loading of structures have improved and helped the cause. But the truss industry also made a concerted effort to minimize these loading differences. Everyone agreed that a truss bid shouldn’t be won based on “less loading,” so they set out to change that. One of the best efforts in accomplishing this was the development of the SBCA Load Guide entitled “Guide to Good Practice for Specifying & Applying Loads to Structural Building Components.” Produced by the Structural Building Component Association (SBCA) in cooperation with the Truss Plate Institute (TPI), the Load Guide was developed with the stated goal of “helping everyone that uses it to more easily understand, define and specify all the loads that should be applied to the design of each structural building component” and “to help assure that all trusses will be designed using a consistent interpretation and application of the code.”

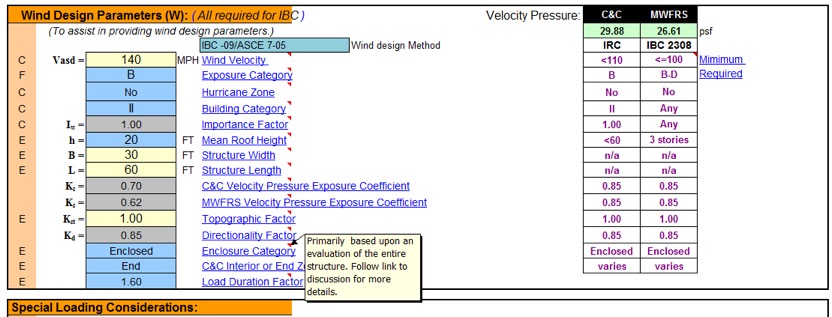

If you are an architect, engineer or a Building Code Official who deals with trusses and you don’t already have the current SBCA Load Guide, I strongly encourage you to check it out (free downloads are available from the SBCA website here.) When fielding questions about loading on trusses, I inevitably refer the inquiring party to the SBCA Load Guide not only for the answer to the question, but for future reference as well. The SBCA Load Guide isn’t just a handy reference to read, it also offers a spreadsheet tool that can be used to calculate loads as well as output the load calculation worksheets. The worksheets can be submitted with the construction documents for plan approval or submitted to the truss manufacturer to be used in the design process.

In addition to providing all of the code and standard loading provisions that apply to metal-plate-connected wood trusses, the SBCA Load Guide also presents the truss industry’s consensus positions and interpretations on provisions that are either unclear as to how they apply to trusses or that have resulted in loading inconsistencies in the past. With the many truss-specific examples and applications covered, it leaves very little room, if any, for further interpretation or question as to how the various code provisions should be applied to trusses.

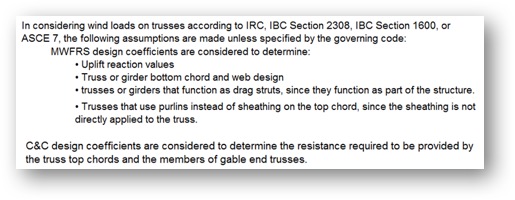

Take wind loads, for example. Wind loading on trusses has been a heavily debated topic over the years, such as whether a truss should be designed for Components & Cladding (C&C), Main Wind Force Resisting System (MWFRS) or both. In fact, wind loading used to be one of the main sources of inconsistencies in truss designs from one company to another. The truss industry has since established a consensus position on this matter and the SBCA Load Guide presents it as follows:

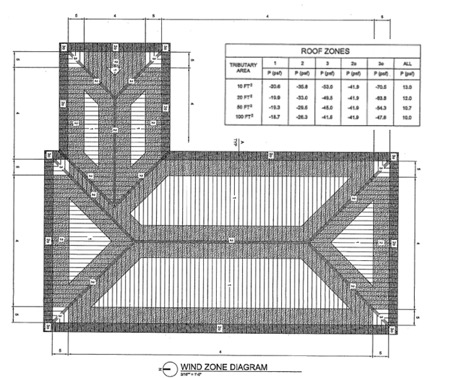

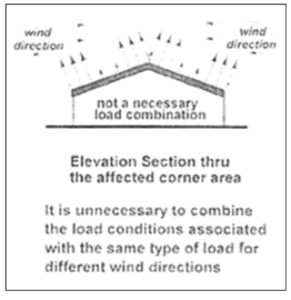

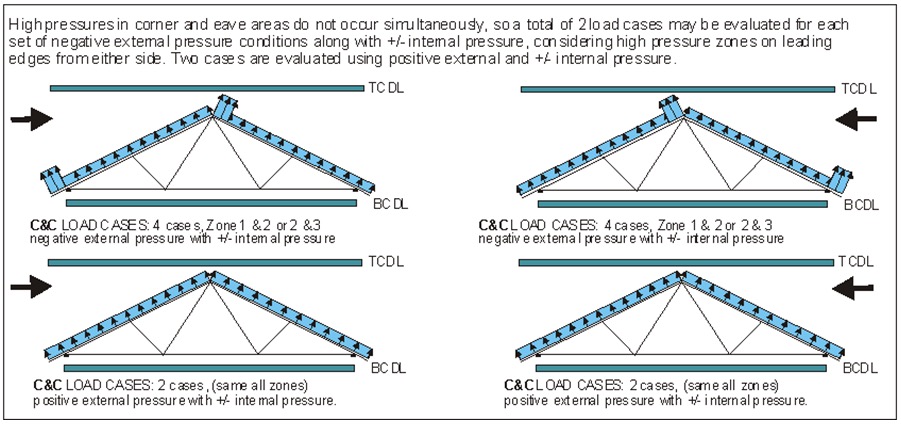

The SBCA Load Guide also pulls information from a variety of resources to help provide more insight into some of the code provisions. For example, in the wind loading section a graphic is reproduced from a Structural Engineers Association of Washington’s handbook (SEAW RSM-03) to clarify the effect of wind directionality on C&C wind pressures for gable/hip roofs, since this consideration is not made clear in ASCE 7.

This clarification is further illustrated in the example wind loading diagrams, which show how wind pressures are evaluated when taking the directionality of the wind into account, i.e., by evaluating the pressures separately with the wind from the left and from the right.

Of course, the SBCA Load Guide is only a guide and is NOT intended to supersede a Building Designer’s design specification. As specified in ANSI/TPI 1, the Building Designer is responsible for providing all applicable design loads to be applied to the trusses:

If you are an architect or engineer who specifies detailed loading schedules for truss systems, great! Your specifications may not need the SBCA Load Guide to ensure that the trusses are accurately loaded as intended in the design of the building. But the SBCA Load Guide still provides a lot of insight as to how the truss industry – and anyone who uses the Load Guide – applies various code provisions to trusses. It might even be an interesting study to see how your specified loads compare to the loading examples in the SBCA Load Guide.

For everyone else who isn’t well-versed in the application of code provisions to wood trusses, the SBCA Load Guide is an invaluable tool. Building Designers, building code officials, truss technicians and truss Designers can all benefit from the Load Guide. As stated in the SBCA Load Guide, one of the industry’s goals is to achieve a greater level of consensus among the largest audience possible on how to load trusses and other structural building components. The more people who read and use the SBCA Load Guide, the more consistency there will be in the interpretation and application of code provisions pertaining to wood trusses, which will help make projects run smoother and most importantly, improve building safety. At Simpson Strong-Tie, we are big fans of tools that work to do that.

If you’ve had experience using the SBCA Load Guide, we’d love to hear about it – please let us know in the comments below!