If you are like me, then you enjoy this time of the year. Instead of looking back and reviewing the events of the past year, this is the month for looking ahead at the year to come and what’s in store. So what is in store for 2015?

For the truss industry, there is a new truss design standard that was just released the last week of December. Still hot off the press, the ANSI/TPI 1-2014 standard is a revision to the 2007 edition and is referenced in the 2015 International Building Codes.

While the 2015 I-Codes might take some time for some municipalities to adopt, others are gearing up for adoption of the 2015 I-Codes as early as mid-2015. Either way, it is always good to know what is in the latest and greatest code-referenced design standards. So here’s a look at the new ANSI/TPI 1-2014 truss design standard:

First, here is a brief primer on the TPI 1 standard. The Truss Plate Institute (TPI) published the first truss design criteria in 1960. Many updates to these design criteria followed after that, and in 1995, TPI published its first ANSI-accredited truss design standard, ANSI/TPI 1-1995. Subsequent editions of this American National Standard have included ANSI/TPI 1-2002, ANSI/TPI 1-2007, and now ANSI/TPI 1-2014. All of the TPI standards, including archived copies going all the way back to TPI-60, are available from TPI (www.tpinst.org). Here is a link to the overview of non-editorial changes from ANSI/TPI 1-2007 to ANSI-TPI 1-2014.

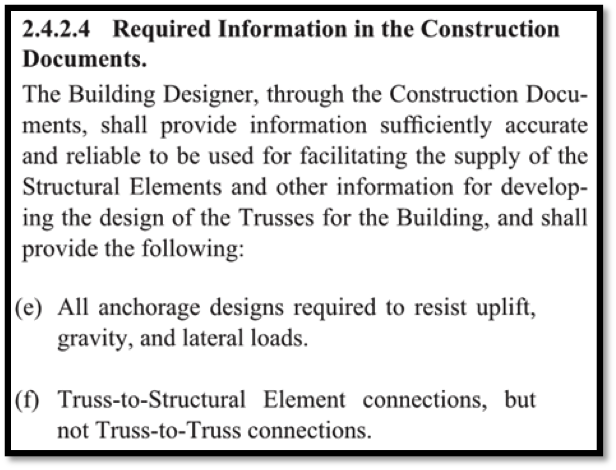

While the 2007 edition included many significant revisions to the previous edition, the 2014 standard has relatively few substantive changes to the 2007 edition, which is good news for those who are still trying to catch up. Chapter 2 covers the design responsibilities involved in metal plate connected wood truss construction and looks different at first glance because it has been reorganized. However, the actual “Design Responsibilities” as they were defined in TPI 1-2007 have not changed.

In short, two separate sections in TPI 1-2007, which address design responsibilities in projects that require registered design professionals and projects that do not, have now been combined into one section. The “Truss Design Engineer” is simply referred to as the “Truss Designer” and the “Registered Design Professional for the Building” is simply the “Building Designer.” If the project requires registered design professionals, then the Truss Designer and Building Designer will be registered design professionals. Regardless of whether or not those two parties are registered design professionals, their responsibilities relating to the design and application of metal plate connected wood trusses are the same, so defining those responsibilities once within the TPI standard simplifies things and makes more sense.

Not new to the wood industry, but new to TPI 1-2014, are provisions for Load and Resistance Factor Design (LRFD). AF&PA incorporated LRFD provisions into the 2005 National Design Specification (NDS) for Wood Construction, and the TPI standard has followed suit, using the same basic approach as the NDS.

The section in TPI 1-2014 with the most changes is the section on deflection criteria. The deflection criteria have been revised in the last three editions of the TPI standard. Starting in TPI 1-2002, a requirement was added to consider creep in total deflection calculations. However, specific creep factors were not specified in the standard and were only presented in the Commentary. In the 2007 edition, creep factors were moved into the standard, and the total deflection calculation explicitly specified a component due to creep of no less than 50 or 100 percent of the initial deflection for long-term loads for dry and green (wet service) use, respectively. This was consistent with the 1.5 and 2.0 creep factors specified in the NDS for total deflection calculations for seasoned and unseasoned conditions.

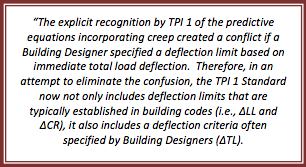

Between the 2007 and 2014 editions, an inconsistency was discovered between the TPI 1 deflection criteria and the deflection limits in the U.S. model building codes. While the intent of the TPI standard was to present the same basic L/xxx deflection limits for Live Load and Total Load as the model building codes, it was discovered that the IBC deflection limits for “DL + LL” were actually intended to address only the creep portion of the dead load deflection plus the immediate live load deflection. So although long-term deflection including proper creep considerations can be an important consideration in the overall design of the building, it is not intended to be used to limit the design of a truss with respect to building-code established limits on vertical deflection.

To resolve the issue of inconsistent methods used in the building industry to specify deflection limits, the 2014 edition now distinguishes between the following:

• “Deflection due to Live Load Plus Creep Component of Deflection due to Dead Load” for purposes of meeting the IBC deflection limits for DD + LL, which is defined as

ΔCR = Δ LL + (Kcr ‐1) x Δ DL

• “Long-Term Deflection”, which includes the full effect of creep but for which there are no explicit deflection limits specified in TPI

• “Deflection due to Total Load”, which is based on the full load (including both dead load and live load), but includes no explicit creep factors. The deflection due to total load has the same deflection limits as the IBC deflection limits for DD + LL, but this is not a mandatory check in TPI; it only applies to trusses if the Building Designer specifies that such a check due to total load be performed. Further, any consideration for creep in that calculation would also have to be specified by the Building Designer.

In recognition of the increased creep in trusses compared to solid sawn beams, the creep factors have been increased to 2.0 and 3.0 for dry and green (wet service) use, respectively. For purposes of deflection checks in accordance with the IBC, these factors reduce to 1.0 and 2.0, respectively, since the equation for “Deflection due to Live Load Plus Creep Component of Deflection due to Dead Load” uses KCR-1 rather than KCR as the factor on the immediate deflection due to dead load.

What does this all mean? For the majority of truss applications (e.g., dry-service), the effect of switching from TPI 1-2007 to TPI 1-2014 will be a change in creep factor from 1.5 to 1.0, unless additional requirements are specified by the Building Designer. Those additional requirements may include a limit on long-term deflection or a check for total load deflection (subject to the TPI deflection limits), including any considerations for creep.

A complete listing of the changes in TPI 1-2014 and more discussion about these changes are available in the TPI 1-2014 Commentary.

Now is your chance to win a copy of the ANSI/TPI 1-2014 standard for your own design library! Simply post a truss-related question, comment or idea for a future truss-related blog topic, and we will enter you into a drawing during the week of Jan 15-22. One winner will be picked at random. We look forward to hearing from you!