If you are a civil engineering student finishing your degree, you are probably starting to explore all the options and opportunities available in the workforce. While structural engineering may be a specialized discipline, there are many paths and backgrounds that can lead someone into an exciting career that is innovatively transforming modern development in cities and towns all over the world.Continue Reading

Happy New Year

Happy Holidays!

How do you Design Sole-Plate-To-Rim-Board Attachments?

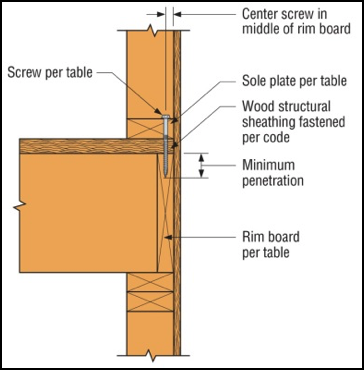

For many years, builders have struggled with the awkward sole-plate-to-rim-board attachment. They often install a few nails and call it good, resulting in a connection with significantly less capacity than needed. This connection is critical to ensure that seismic and wind loads are adequately transferred to the lateral-force-resisting system. With screws becoming much more common in construction, we saw an opportunity to address this problem.

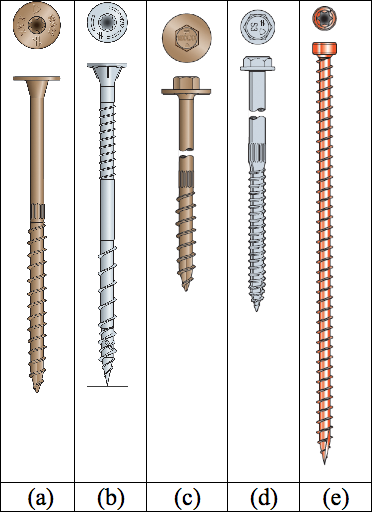

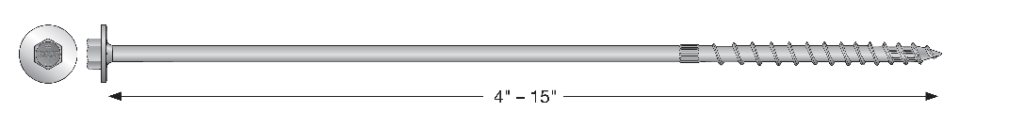

We offer a variety of structural wood screws that have shank diameters ranging from 0.135″ to 0.244″. They form our Strong-Drive® line of structural fasteners. The Simpson Strong-Tie® Strong-Drive SDWC Truss, SDWH Timber-Hex, SDWS Timber, SDWV Sole-to-Rim and SDS Heavy-Duty Connector structural wood screws as shown in Figure 1 can be used to attach sole plates to a rim board as shown in Figure 2. These screws provide structural integrity in the wall-to-floor connection.

The sole-to-rim connection is considered a dry service location. When the sole plate and the rim are both clean wood (not treated), then any of the screws can be used as long as they meet the design loads. However, if one or both members of the connection are treated with fire retardants or preservatives, then you must use the SDWS Timber screw, SDWH Timber-Hex screw or SDS Heavy-Duty Connector screw. The SDWS, SDWH and SDS screws all have corrosion-resistance ratings in their evaluation reports.

The Strong-Drive SDWV structural wood screw has the smallest diameter among these screws. The SDWV is 4″ long and has a 0.135″- diameter shank, and a large 0.400″-diameter ribbed-head with a deep six-lobe recess to provide clean countersinking. It is designed to be fast driving with very low torque. The Strong-Drive SDWS offers one of the larger diameters. It has a 0.220″-diameter shank and is offered in lengths of 4″, 5″ and 6″. It has a large 0.750″-diameter washer head which provides maximum bearing area. Longer screws allow designers to meet the minimum penetration requirement into a rim board, when the sole plate is a 3x or a double 2x member.

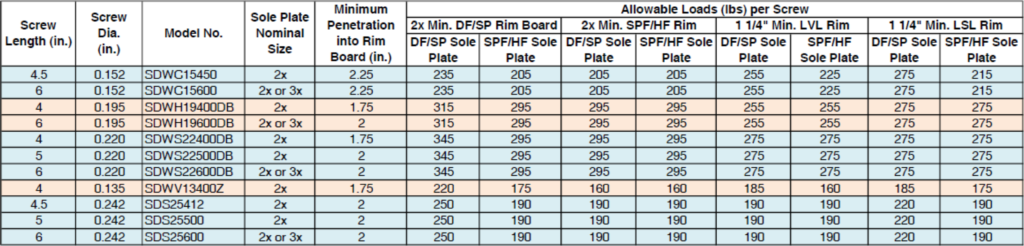

We have tested various combinations of sole plates, floor sheathing, and rim boards. Typical test assemblies were built and tested with two (2) Strong-Drive® screws spaced at either 3″ or 6″. Results were analyzed per ICC-ES AC233, “Acceptance Criteria for Alternate Dowel-type Threaded Fasteners.” The allowable loads listed in Table 1 are based on the average ultimate test load of at least 10 tests, divided by a safety factor of 5.0, and are rated per single fastener. The results of these tests can be found in the engineering letter L-F-SOLRMSCRW16.

The evaluated sole plates include southern pine (SP), Douglas fir-larch (DF), hem-fir (HF), and spruce-pine-fir (SPF) in single 2x, 3x or double 2x configurations. Floor sheathing thicknesses are allowed up to 1 1/8″ thick. Rim boards can be LVL or LSL structural composite lumber or DF, SP, HF or SPF sawn lumber. The load rating also assumes that the floor sheathing is fastened separately and per code.

See strongtie.com for evaluation report information if it is needed.

As a Designer, you can specify any of these Strong-Drive screws that fit your design requirements. Please visit our website and download L-F-SOLRMSCRW16 for more details.

Good luck!

Galvanic Corrosion

This week we are blogging about being “galvanic,” and we don’t mean with respect to people, but with respect to the corrosion that occurs between dissimilar metals.

Here is a question, and it is not a joke: What is one significant result that can occur when you have both electrochemical activity and intimate contact? The answer is galvanic corrosion.

Galvanic corrosion can take place when two or more metals of different electrochemical activity are in intimate contact in the presence of an electrolyte. The dissimilar metals form a galvanic couple, and with the aid of the electrolyte, a galvanic current flows between the metals of the galvanic couple. The more anodic metal corrodes in the presence of the more cathodic metal. In fastening systems, this can be a significant issue because the metal of the fastener often does not match that of the connection materials, making their electrochemical activity dissimilar.

Let’s examine the requirements for galvanic corrosion to occur.

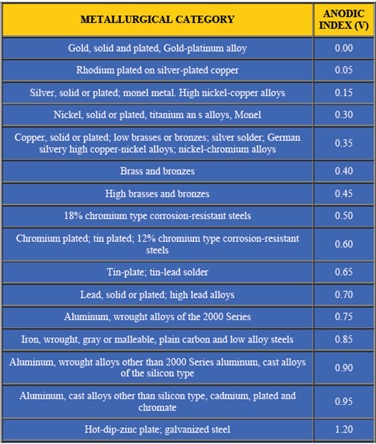

First – In the most common instance, the metals are dissimilar, which means that the metals have different chemical potentials. You may be familiar with the galvanic series where metals are rated by their tendency to give up electrons in a salt-water solution. See Figure 1 for a chart of the galvanic series. The chart is structured with the most cathodic metals at the top and progresses to the most anodic at the bottom. The anodic index shown in the chart is normalized so that gold is the minimum numerical value, while zinc has the greatest numerical value. Stainless steel (300 series) is hidden in the terminology of “18% Chromium type corrosion-resistant steels.” In this chart, the stainless steel is assumed to be passivated.

Second – The metals must be in direct contact.

Third – An electrolyte must be present to facilitate the movement of electrons. The electrolyte in construction environments is usually plain water that occurs in the form of precipitation, condensation or water splash. Electrolytes that are solutions of chlorides (for example, salt water) are particularly effective electrolytes because they are more conductive.

The size of the anodic and cathodic parts can also be important in galvanic corrosion. If the anodic area is small relative to the cathodic exposed area, then the severity of the anodic corrosion is amplified. We can write an equation to explain the role of area in the galvanic process. We know that no corrosion will occur if the corrosion current density (icor) in μA/cm2 is the same for the anode (icor-a) and the cathode (icor-c). Here we are using a and c as subscripts to identify the anode and the cathode in the galvanic system. We know that current density is a function of total anodic current (I) in μA (where italicized A is amps), and the exposed area (A) is in cm2, which (according to ASTM G102-89) can be written as

icor = Icor/A

No galvanic corrosion transpires if icor-a for the anodic material is equivalent to icor-c of the cathodic material, which is to say Icor/Aa = Icor/Ac. However, when Ac ≠ Aa, then the corrosion function is not balanced, and relative areas can drive the severity of the galvanic reaction. Inasmuch as area can affect the galvanic process, it will help connection performance if the more anodic material is larger than the more cathodic material. And, by making the Aa>>Ac, we can arrest or minimize the galvanic process. Generally, this means it is best to have a fastener that is more cathodic than the materials being fastened.

We also know that the environment can affect galvanic activity. The differential in the anodic index of dissimilar metals is amplified in harsh environments, but in controlled environments, a greater differential in anodic index can be tolerated.

Let’s summarize some best fastening practices for preventing galvanic conditions that could undermine an otherwise good connection design (Claus, L. 2014. “Galvanic Corrosion.” Fastener Technology, April, pp. 64–66.):

- Use fasteners that are galvanically similar to the connection materials.

- Isolate the dissimilar materials by using a plastic washer or durable coating.

- Prevent entrapment of water or shield the connection from direct weather exposure.

- If the fasteners are dissimilar from the connection materials, choose a fastener that is cathodic relative to the connection materials.

)

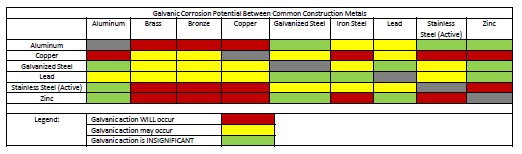

Some good information is available that can help to avoid a galvanic design challenge. First, see Figure 2. This chart provides color-coded galvanic compatibility that is fast and easy to use. The chart suggests material combinations where there will be galvanic action (red), material combination that might demonstrate galvanic activity (yellow), and material combinations that will have insignificant galvanic activity (green).

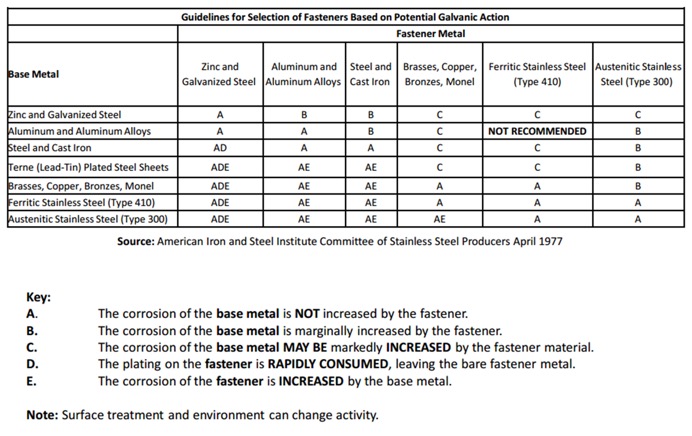

Then see Figure 3 because it gives more information about choices of materials for the fastener and connection materials. Here the probable results of galvanic corrosion to the fastener and base metals are described for various common combinations of common construction materials. It will help to explain which parts of the connection will be affected by galvanic corrosion and how severe the corrosion is likely to be.

We know that you have many challenges when designing fastener connections, and it is our hope that this discussion helps you make informed choices when fastening dissimilar materials. Remember: Galvanic corrosion happens! Let us know if you have any comments.

Pile Construction Fasteners – New and Expanded Applications

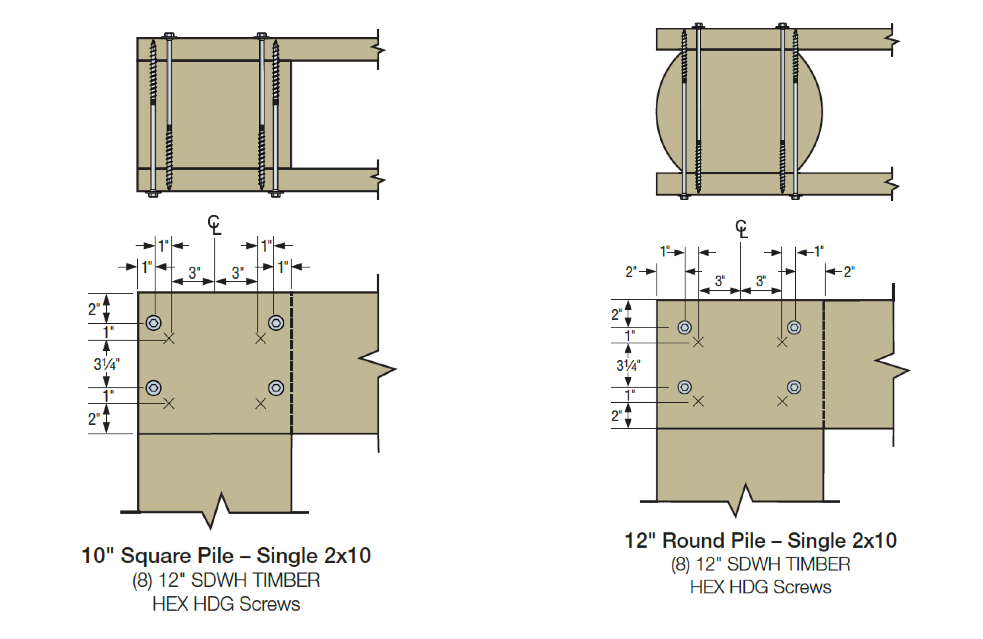

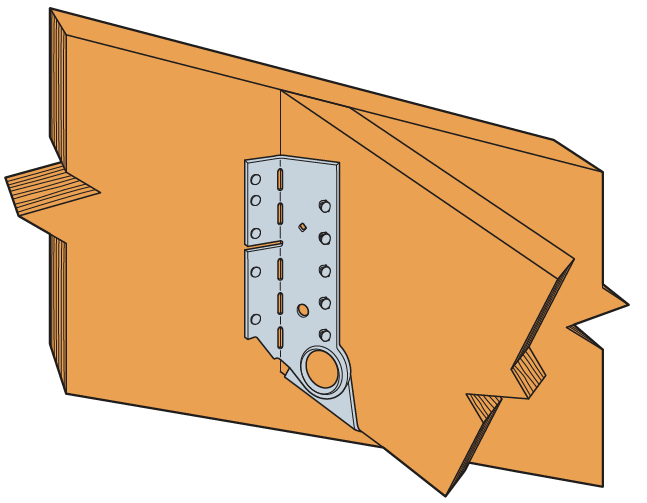

The majority of Simpson Strong-Tie fasteners are used to secure small, solid-sawn lumber and engineered wood members. However, there is a segment in the construction world where large piles are the norm. Pile framing is common in piers along the coast, elevated houses along the beach, and docks and boardwalks.

While the term “pile” is generic, the piles themselves are not generic. They come in both square and round shapes, as well as an array of sizes, and they vary greatly based on region. The most common pile sizes are 8 inches, 10 inches, and 12 inches, square and round, but they can be found in other sizes. The 8-inch and 10-inch round piles are usually supplied in their natural shape, while 12-inch round piles are often shaped to ensure a consistent diameter and straightness. All piles are preservative-treated.

Historically, the attachment of framing to piles has been done with bolts. This is a very labor-intensive method of construction, but for many years there was no viable fastener alternative. Two years ago, however, Simpson Strong-Tie introduced a new screw, the Strong-Drive® SDWH Timber-Hex HDG screw (SDWH27G), specifically designed for pile- framing construction needs. It can be installed without predrilling and is hot-dip galvanized (ASTM A153, Class C) for exterior applications.

Simpson Strong-Tie tested a number of different pile-framing connections that can be made with the SDWH27G screw. This blog post will highlight some of the tested connections. More information can be found in the following three documents on our website:

- The flier for the SDWH Timber-Hex HDG screw: F-FSDWHHDG14 found here.

- The engineering letter for Square Piles found here.

- The engineering letter for Round Piles found here.

The flier provides product information, and the engineering letters include dimensional details for common pile-framing connections that were tested.

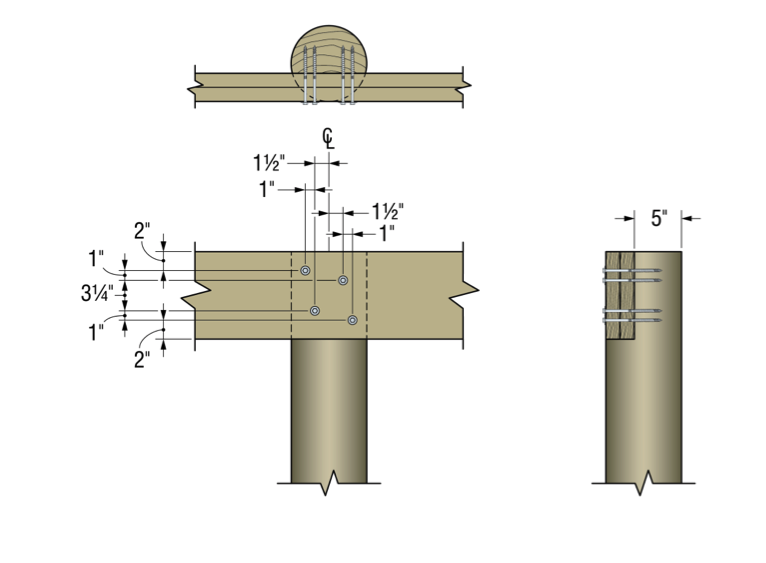

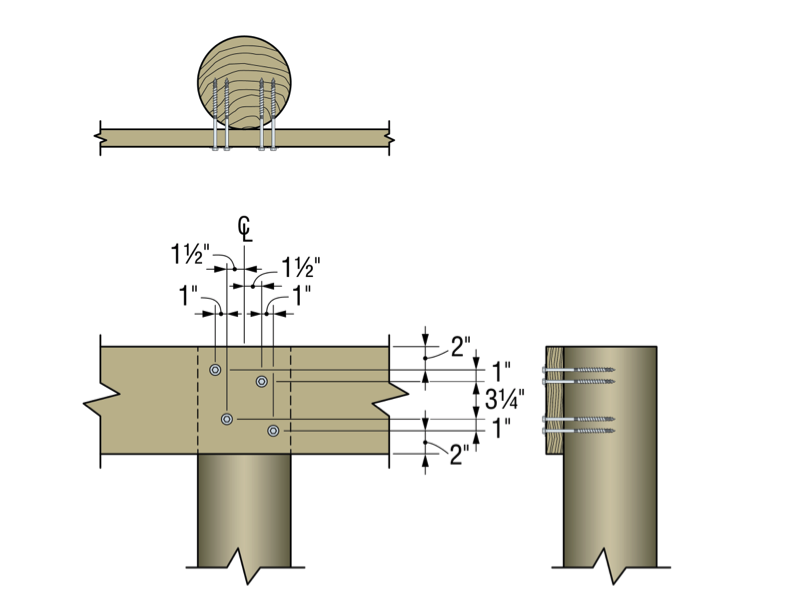

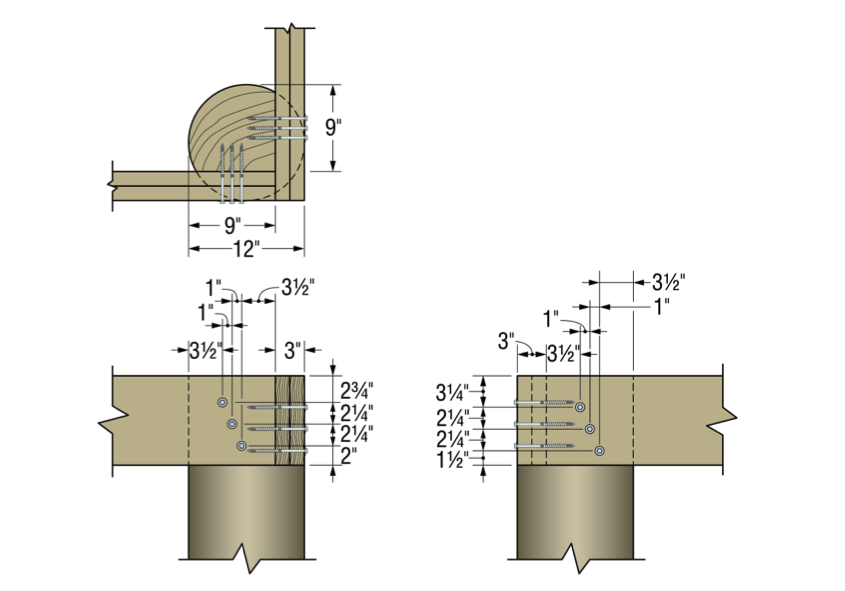

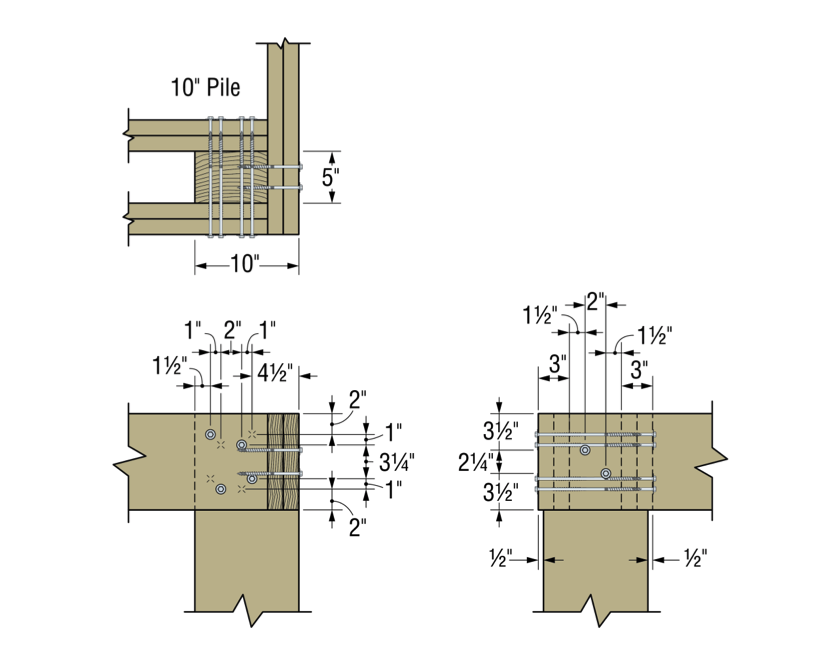

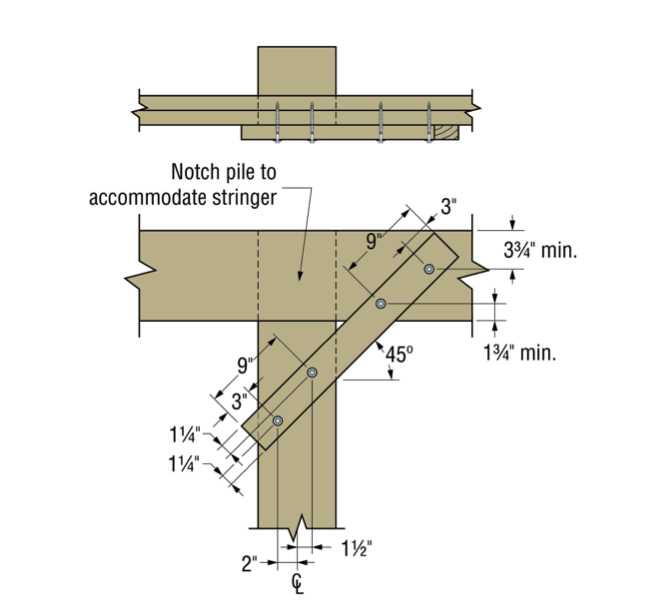

Piles are typically notched or coped to receive a horizontal framing member called a “stringer.” The coped shoulder provides bearing for the stringer and serves as a means of transferring gravity load to the pile. The SDWH27G can be used to fasten framing to coped and non-coped round and square piles.

The connections that we tested can be put into four general groups that include both round and square piles:

- Two-side framing on coped and non-coped piles

- One–side framing on coped and non-coped piles

- Corner framing on coped piles

- Bracing connections

Additionally, the testing program included four different framing materials in several thicknesses and depths:

- Glulam

- Parallam

- Sawn lumber

- LSL/LVL

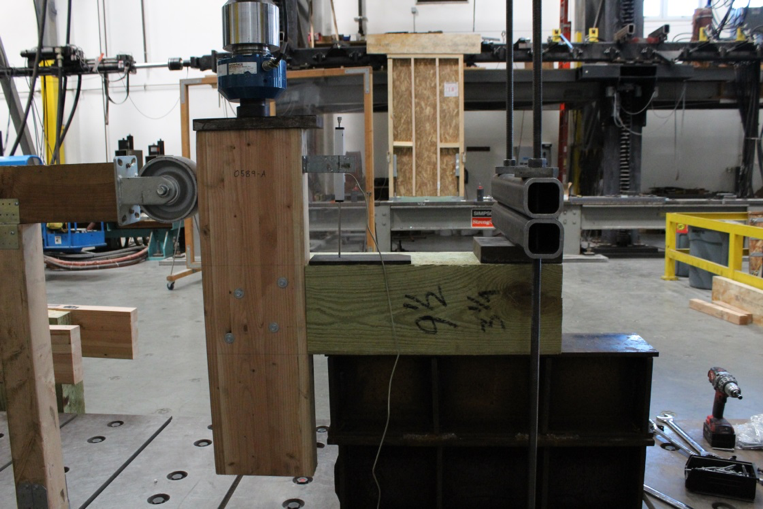

The total testing program included more than 50 connection conditions that represented pile shape and size, framing material and thickness and framing orientation and details. We assigned allowable uplift and lateral properties to the tested connections using the analysis methods of ICC-ES AC13. Figures 2 and 3 show some of the tested assemblies.

Figures 4 through 9 illustrate some of the connections and details that are presented in the flier and engineering letters.

Some elements of practice are important to the design of pile-framing connections. Some of the basic practices include:

- For coped connections, the coped section shall not be more than 50% of the cross-section.

- For coped connections, the coped shoulder should be as wide as the framing member(s).

- Fastener spacing is critical to the capacity of the connection.

- When installing fasteners from two directions, lay out the fasteners so that they do not intersect.

In many cases, pile-framing connections use angled braces for extra lateral support. The SDWH27G can be used in these cases too.

In the flier and engineering letters previously referenced, you will find allowable loads and specific fastener specifications for many combinations of stringer and pile types and sizes.

What have you seen in your area? Let us know – perhaps we can add your conditions to our list.

FRP Concrete Strengthening – Five Case Studies

Fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composite systems can be used to strengthen walls, slabs and other concrete or masonry members in buildings and other structures. The case studies below show ways in which Composite Strengthening Systems™ (CSS) provide valuable solutions for strengthening buildings and other structures for our customers.

Residential Project in San Francisco

The homeowner for this project wanted to repair some spalling concrete on his concrete piers and also wrap the piers with FRP. We worked with the contractor and homeowner to design a cost-effective solution. This was a successful project for all involved, since the alternative was to jacket the piers with costly and unsightly steel jackets.

School Project in Argentina

The goal of the project was to analyze a standard design of approximately 400 schools in Argentina that were built in the 1980s and to make recommendations to retrofit the structures to meet current seismic code requirements. On analysis, it was found that columns were in need of shear reinforcement for the schools to meet the new seismic requirements.

Hospital Project in Butler, PA

The Engineer of Record on this project wanted to provide continuity across the slab construction joints, something which the existing rebar did not provide. We provided a design of Near-Surface-Mounted (NSM) laminates, which are installed in saw-cut grooves in the top of the concrete slab. This installation allows a flush finished surface, important for allowing the floor finishes to be installed on the slab.

Silo Project in Garden City, IA

The concrete silos on this project had spalling at the top portion, which caused a hazard at this site. After repairing the concrete, we provided a ring of carbon fabric to assist in keeping the top concrete of the silos solid for years to come.

Bridge Project in MN

MNDOT wanted to gain experience working with our CSS products on one of their bridges. We worked with their staff to design several types of strengthening solutions for bridge pier caps and columns. We then provided onsite installation training for the MNDOT maintenance staff to install the FRP products on the bridge.

We recognize that specifying Simpson Strong-Tie® Composite Strengthening Systems™ is unlike choosing any other product we offer. Leverage our expertise to help with your FRP strengthening designs. Our experienced technical representatives and licensed professional engineers provide complimentary design services and support – serving as your partner throughout the entire project cycle. Since no two buildings are alike, each project is optimally designed to the Designer’s individual specifications. Our pledge is to address your specific condition with a complete strengthening plan tailored to your needs, while minimizing downtime or loss of use, at the lowest possible installed cost.

Your Partner During the Project Design Phase

During the Designer’s initial evaluation or preparation of the construction documents, Simpson Strong-Tie can be contacted to help create the most cost-effective customized solution. These plans include detailed design calculations for each strengthening requirement and design drawings with all the necessary details to install the CSS system. Simpson Strong-Tie Engineering Services will work closely with the Design Engineer to provide all the necessary information required to design the system.

Why Use Our Design Services?

- Assess feasibility studies to ensure suitable solutions to your application

- Receive customized FRP strengthening solutions

- Work with our trained contractor partners to provide rough-order-of-magnitude (ROM) budget estimates

- Collaborate during the project design phase

- Receive a full set of drawings and calculations to add to your submittal

- Maintain the flexibility to provide the most cost-effective solution for your project

- Gain trusted technical expertise in critical FRP design considerations

Learn more: Webinar – Introducing Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM)

In this free webinar we dive into some very important considerations including the latest industry standards, material properties and key governing limits when designing with FRCM.

Continuing education credits will be offered for this webinar.

Participants can earn one professional development hour (PDH) or 0.1 continuing education unit (CEU).

For complete information regarding specific products suitable to your unique situation or condition, please visit strongtie.com/css or call your local Simpson Strong-Tie RPS specialist at (800) 999-5099.

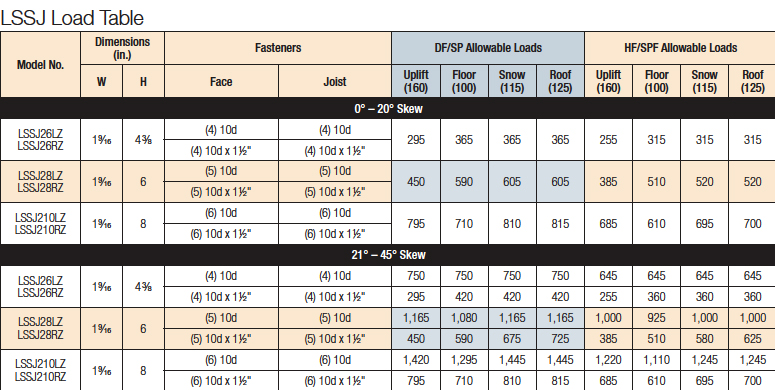

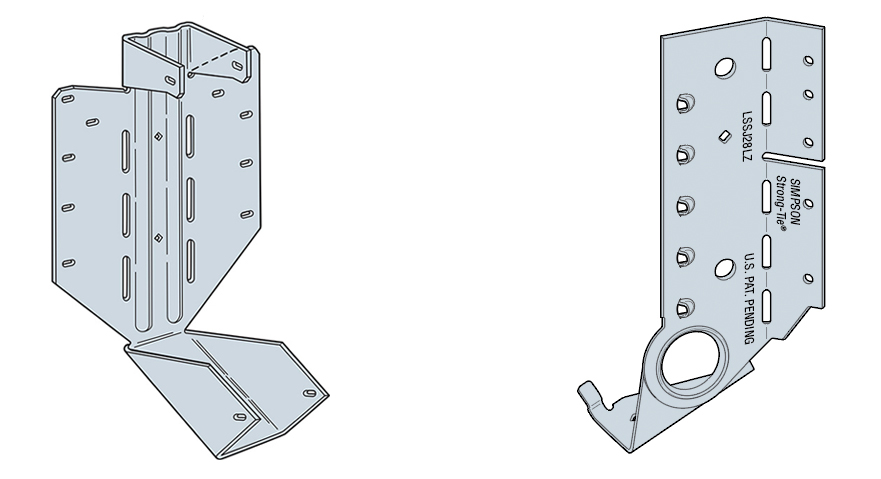

New LSSJ Hanger Strengthens Jack Rafter Connections

When our company is considering a new or improved product, we like to start out by talking to our customers first. That’s what we did recently with a connector improvement project for attaching jack rafter hangers in roof framing – and we got lots of feedback!

We heard from installers that they really wanted a hanger that could be easily adjusted in the field for different slopes and skews. We were asked whether we could design a hanger that could be installed after the rafters were already tacked into place to support construction sequencing and retrofit applications. Also, having a hanger that could be installed from one side was a popular time-saving request.

Our Engineering innovation team took all this feedback and closely evaluated our current selection of hangers. After much consideration, the team decided that rather than adapt one of our existing hangers, they would try to come up with an all-new design that would satisfy our customers’ most pressing needs.

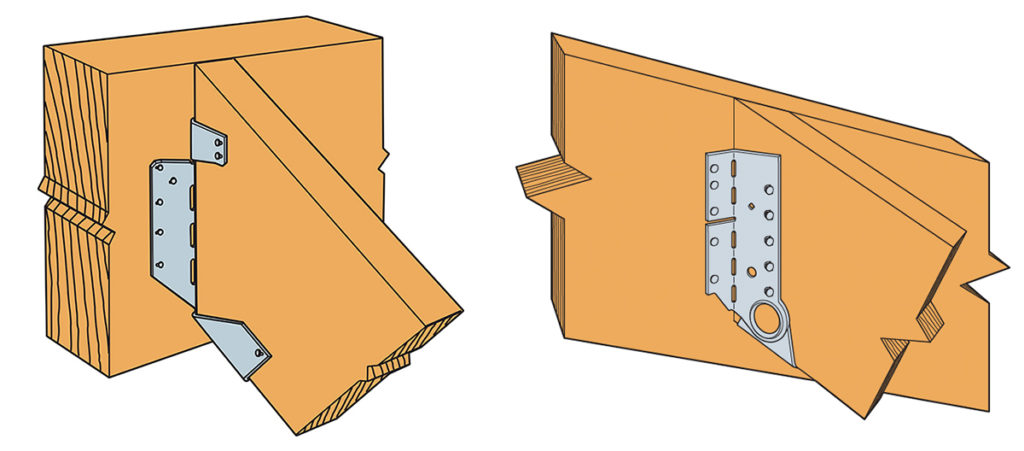

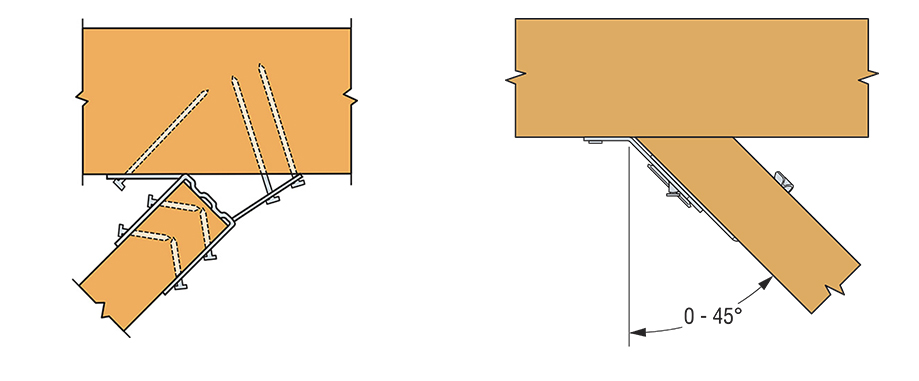

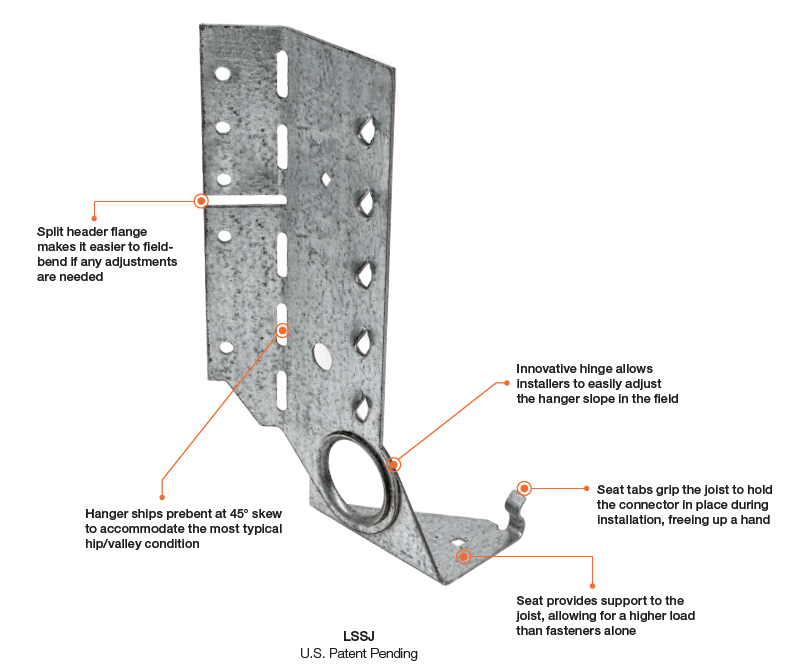

After months of designing and testing prototypes in the lab and in field trials, the answer was yes. The result is our new LSSJ field-adjustable jack hanger. It’s an innovative field-slopeable and field-skewable hanger that features a versatile hinged seat. This new design allows it to be adjusted to typical rafter slopes, with a max slope of 12:12 up or down.

What is a jack hanger and why does it provide a better connection than nails alone?

There are two basic types of wood roof construction: framed roof construction (stick framing) as shown above, and truss assembly. The main difference is that stick assembly takes place onsite, while trusses are prefabricated and ready to place. In the United States, the number of truss-built roofs versus stick-frame roofs is about two to one. The LSSJ jack hanger is used for stick-frame construction and provides a connection between the jack rafter to either the hip rafter or the valley rafter as shown below.

Connecting a 2X jack rafter to a hip is hardly new. The hardest thing is making a good compound miter cut – something an experienced framer can figure out (and most engineers marvel at). In many parts of the country, these are simply face-nailed into place. Often there isn’t a lot of engineering that goes into that connection. However, a closer look raises a couple of questions.

Random Nail Placement

Where exactly are those nails going? When there’s no seat support for the rafter, the allowable shear is reduced per the NDS depending on where the lowest nail on the rafter is. This is based on the split that develops at the lowest fastener. The LSSJ provides a partial seat which not only meets the bearing requirement of section R802.6 of the IRC but also delays the type of splitting found in a nailed-only connection.

Consistent Nail Placement

The LSSJ conforms to the bottom of the jack rafter slope and ensures consistent nail placement on both the rafter and the hip. Consistent nail placement promotes consistent performance based on testing (or as consistent as wood gets)! The highest nail on the hip is located near the neutral axis if the hip is one size deeper than the rafter. This assures that not all the load is focused at the bottom of the hip.

A Closer Look at the LSSJ Jack Hanger

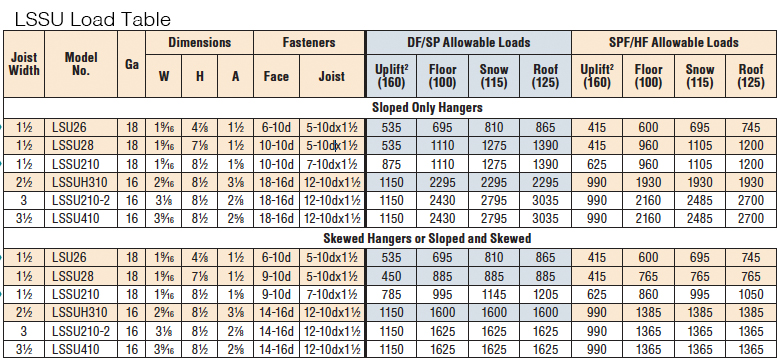

Some of our customers may be familiar with our current product, the LSSU, which is used for the same connection. Here’s a closer look at the improvements that the LSSJ offers.

You can see the differences and improvements just by looking at these hangers, installations and load tables. Here’s a different way of showing the advances and benefits of the LSSJ:

One of the greatest improvements is the fact that there are fewer nails to install in the LSSJ, and the loads are very similar if not better.

In addition to the LSSJ, Simpson Strong-Tie offers a full line of connectors for wood-framed sloped roofs, including:

We look forward to hearing from you about our newest innovation. For more information about the LSSJ hanger, please see strongtie.com.

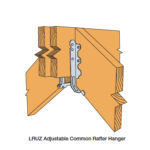

Cold-Formed Steel Curtain-Wall Systems

In August 2012, Simpson Strong-Tie launched a comprehensive, innovative solution for curtain-wall framing. Our lead engineer for developing our line of connectors for curtain-wall construction explains the purpose of the curtain wall with the illustrations below.

First, curtain walls are not what you put up if you shared a room with your brother and sister when you were growing up. When I first learned about the use of cold-formed steel curtain walls, I laughed and thought: “Gosh, how useful this would be for someone growing up with 5 siblings in one bedroom!” I have always enjoyed the sense of humor that our engineers use to help explain technical topics.

First, curtain walls are not what you put up if you shared a room with your brother and sister when you were growing up. When I first learned about the use of cold-formed steel curtain walls, I laughed and thought: “Gosh, how useful this would be for someone growing up with 5 siblings in one bedroom!” I have always enjoyed the sense of humor that our engineers use to help explain technical topics.

Curtain walls can be described as exterior building walls with the primary purpose of protecting the interior building against the exterior weather and natural phenomena such as sun exposure, temperature changes, earthquakes, rain and wind.

To put it in structural terms, a curtain-wall system consists of non-load-bearing exterior walls that must still carry their own weight. Curtain walls are not part of the primary structural framing for the building, but they typically rely on the primary structural framing for support. Additionally, curtain walls receive wind and seismic loads and transfer these forces to the primary building structure.

Types of Curtain Walls

Glass and cladding curtain walls make up two basic types of curtain-wall systems. Glass curtain-wall systems are usually designed using aluminum-framed walls with in-fills of glass. The cladding curtain wall is a system with back-up framing that is covered in some type of cladding material. The cladding curtain-wall system is the type in which Simpson Strong-Tie products can be used.

The back-up framing is the structural element of the curtain-wall system. It is typically constructed with cold-formed steel studs ranging from 31/2″ to 8″ deep, in 33 mil (20 ga.) to 97 mil (12 ga.) steel thicknesses. The framing studs are typically spaced at 16″or 24″ on center. There are many different types of cladding materials. They include, but are not limited to, exterior insulation finish systems (EIFS), glass-fiber-reinforced concrete (GFRC), bricks, metal panels and stone panels.

The back-up framing is the structural element of the curtain-wall system. It is typically constructed with cold-formed steel studs ranging from 31/2″ to 8″ deep, in 33 mil (20 ga.) to 97 mil (12 ga.) steel thicknesses. The framing studs are typically spaced at 16″or 24″ on center. There are many different types of cladding materials. They include, but are not limited to, exterior insulation finish systems (EIFS), glass-fiber-reinforced concrete (GFRC), bricks, metal panels and stone panels.

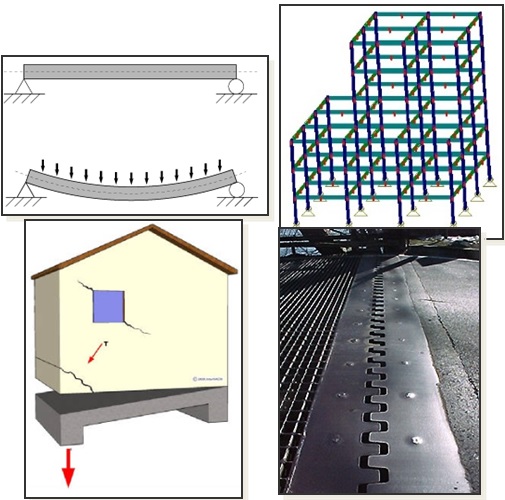

One essential function of the curtain wall is to allow for relative movement between the curtain-wall system and the main building structure. At first, it was not obvious to me why making this allowance was necessary, but our product development team creatively explained some of the reasons why this is an important must-have feature for curtain walls.

First, the primary building will move up and down as it is loaded and unloaded by the live-load occupancy, similar to beam live-load deflections.

First, the primary building will move up and down as it is loaded and unloaded by the live-load occupancy, similar to beam live-load deflections.

Second, the structure sways and has torsional displacement due to movement from lateral wind or seismic loads.

Third, concrete structures typically encounter creep and shrinkage, and there may be foundation differential settlement or soil compression from high-gravity loads.

Lastly, the temperature differential may cause the building elements to expand and contract, which, again, can result in relative movement between structural elements. This is similar to a bridge’s steel plate expansion joint system.

And if you are a curious designer like me, you probably wonder why the relative vertical moment is so significant in engineering design.

One key reason is to ensure that the curtain walls do not collect gravity loads from the building, so as to prevent overloading and possible failure of the stud framing. In addition, a well-designed curtain-wall system needs to retain the primary structural load path as intended by the building designer.

The other reason is to protect the cladding of the building. If you remember earlier, the cladding material may be marble, granite or natural stones that are often very expensive and heavy. In some cases, the cladding can be one of the most expensive systems in a building. And there are times when it’s much more cost-effective to design for relative movement than it is to over-design structural framing to address the stringent deflection requirements.

Construction Type

Bypass framing is a term that is often used in curtain-wall construction. In this system, the metal studs bypass the floor and hang off the outside edges of the building. You can see from the illustration how the studs run past, or bypass, the edge of the slab. In this case, the studs are supported vertically on the foundation at the bottom, and then run continuously past multiple floor levels.

In steel construction, concrete fill over metal deck is typically constructed with a heavy-gauge bent plate or structural angle. Connectors can attach directly to the steel angle or the web of an edge beam.

It may seem that this type of construction is too complex and requires great efforts to detail the many connections needed to hang the curtain wall off the outside of the building. So what are the compelling reasons to choose bypass framing construction?

Bypass framing can accommodate flexibility for the architect. In another words, the bypass configuration easily allows architects to create reveals, set-backs and other architectural features. Plus, there are fewer joints to detail for movement when stud length can run continuously for several floors. Another benefit is that the exterior finish can also be installed on a curtain-wall system with a tighter tolerance than the edge of the structure.

One other special bypass framing type is known as ribbon window or spandrel framing. Ribbon windows are a series of windows set side by side to form a continuous band horizontally across a façade. The vertical deflection for this type of bypass framing is typically accommodated at the window head. This type of bypass usually works well for panelized construction.

Another common curtain-wall system is infill framing, where the studs run from the top of one floor to the underside of the floor above. Sometimes it’s a challenge to attach bypass framing to the edge of thin concrete slabs. In the following illustration, deflection is designed at the top track of wall panels.

In Part 2 of this blog post series, I will provide more details about how we have innovated products to be used for this application, plus a more comprehensive post about the products we offer and how they are typically used.

In Part 2 of this blog post series, I will provide more details about how we have innovated products to be used for this application, plus a more comprehensive post about the products we offer and how they are typically used.

In the meantime, you can check out our product offering. Our recent SC slide-clip and FC fixed-clip connectors are designed for high-seismic areas.

I would like to invite you to comment and provide feedback on this topic and tell us whether you’ve had any experience working with a Designer on a CFS curtain-wall project. If you are a Designer who specializes in this discipline, how are you designing curtain-wall systems for seismic forces?

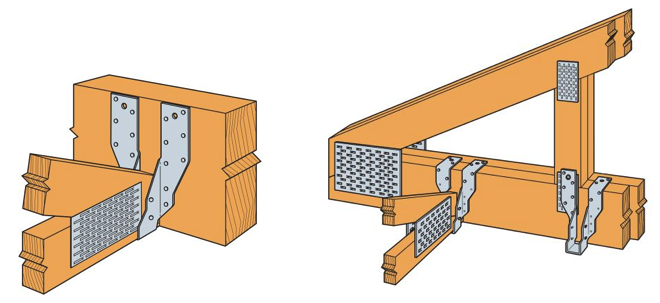

How to Pick a Connector Series – Truss Hangers

In our second blog in the “How to Pick a Connector Series,” Randy Shackelford discussed the various considerations involved in selecting a joist hanger. So why is this blog post about truss hangers? A hanger is a hanger, right? Before I moved into the Engineering Department at Simpson Strong-Tie, I was the product manager for our Plated Truss product line. I can assure you that there is a bit more that goes into the selection (and design) of a truss hanger than does into selecting a joist hanger!

Of course, all of the considerations that were covered in the joist hanger blog apply to truss hangers as well. This blog post is going to discuss some additional considerations that come into play in selecting a hanger for a truss rather than a joist, and how some hangers have features designed especially for trusses.

The first (and most obvious) truss-specific consideration is the presence of webs. Because of truss webs, top-flange hangers are not as conducive to truss applications as they are to joist applications. A better alternative for trusses is an adjustable-strap hanger that can be installed as a top-flange hanger or face-mount hanger. Take the THA29, for example, Simpson’s first hanger developed specifically for the truss industry (circa 1984). It can accommodate different girder bottom chord depths, which eliminates the need for multiple SKUs, and the straps can be field-formed over the top of the girder bottom chord to reduce the number of fasteners (just like top-flange hangers). When a web member is in the way of the top-flange installation method, the straps can be attached vertically to the web in a face-mount installation instead.

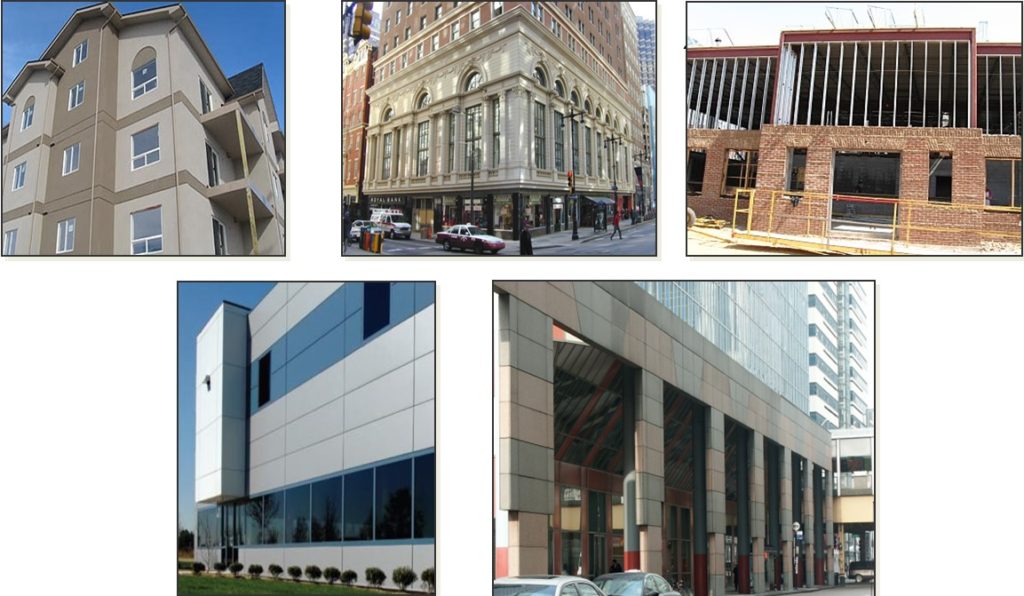

What if the web at that location isn’t vertical? You can still install the strap onto the web, but if any nails land in the joint lines formed by the intersection of the wood members, they cannot be considered effective. Therefore, the hanger allowable load may need to be reduced to account for ineffective header nails. This alternative installation is acceptable for any face-mount hanger located at a panel point as shown in our catalog (see detail below).

Although very versatile, not all adjustable-strap hangers can be installed on all sizes of bottom chords. Our catalog specifies a C-dimension for these hangers, which corresponds to the height of the side-nailing flanges. If that dimension exceeds the height of the bottom chord, then the straps cannot be field-formed as needed for the top-flange installation. And if the hanger isn’t located at a panel point, nailing the straps to any diagonal web that the straps can reach (see photo below) is not an acceptable option!

Another unique consideration that goes into the selection of a truss hanger is the heel height of the carried truss. A truss with a short heel height installed into a tall hanger will likely leave air (or “daylight,” as I call it) behind a lot of the nail holes running up the side flanges. When nail holes in a hanger have air behind them instead of wood, this equates to a reduction in hanger capacity. So when the carried truss has a heel height that is much less than the depth of the carrying member (and the hanger), it is important to use the appropriate hanger capacity for that condition and not overestimate the hanger’s capacity. Refer to our technical bulletin T-REDHEEL for allowable loads for reduced heel height conditions.

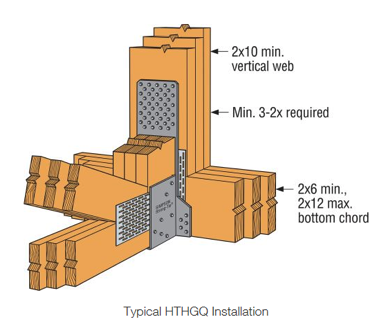

Because trusses are capable of carrying a lot of load – and producing large reactions – hangers for truss applications often require larger capacities than joist hangers. Unfortunately, there is only so much capacity that can be achieved from a hanger that fits entirely onto a girder truss bottom chord. Therefore, in order to use our highest load-rated truss hangers, a properly located vertical web is required, and the web must be wide enough for the hanger’s required face fasteners and minimum edge distances. The more capacity that is required, the more fasteners it takes, and the wider the vertical web must be. Our highest-load-rated truss hanger that installs with screws is the HTHGQ. It has a maximum download capacity of 20,735 lb., but it requires a minimum 2×10 vertical web. The THGQ/THGQH series can be installed onto as small as a 2×6 web, but the maximum possible capacity on a 2×6 web is 9,140 lb.

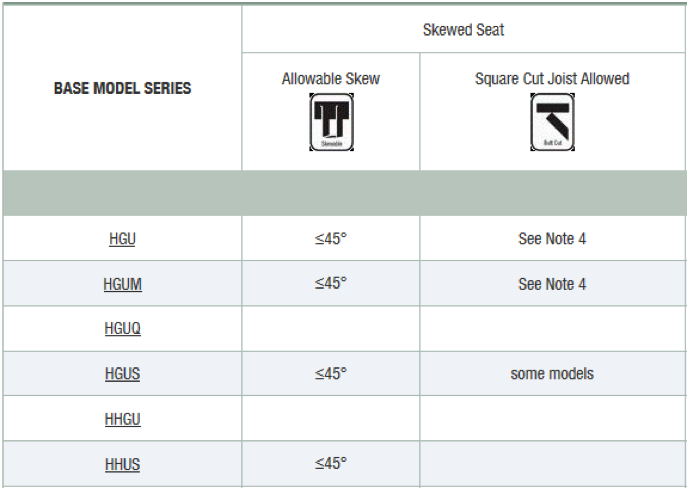

In addition to high-capacity hangers, truss applications often require high-capacity skewed hangers. When selecting skewed hangers, it’s important to realize that hangers with custom skew options usually have a reduction that must be applied to the hanger’s 90-degree capacity. Another important factor that is sometimes overlooked in the selection of skewed hangers is whether the carried member is square-cut or bevel-cut. When the member is square cut – as in the case of trusses – not only does this typically result in a greater reduction in capacity, but some skewed hangers cannot be used at all with square-cut members. For example, the fastener holes on the side flange may not be located far enough away from the header to accommodate square-cut members. See the photo below for an example of what can happen if a skewed hanger that is intended for a bevel-cut member is used for a truss.

As discussed in the previous hanger blog, face-mount hangers offer the advantage of being installed after the joist (or truss) is installed. What if the truss is installed prior to the hanger and a gap exists between the truss and the carrying member? In that case, the best option may be to select a truss hanger that was designed with this type of installation tolerance in mind, the HTU hanger. Other face-mount truss hangers that use double-shear nailing are great when gaps are limited to ⅛” or less, but their capacities take a pretty large hit when the gap exceeds ⅛” (see our previous blog Minding the Gap in Hangers for more information). The HTU was designed to give an allowable load for up to a ½” gap between the end of the truss and the carrying member. In addition, it has built-in nailing options to accommodate short heel heights even in the taller models – definitely a truss hanger!

Finally, there is one more thing to consider when selecting a face-mount hanger for a truss application, which relates to how tall the carrying member is compared to the hanger. Assuming the bottom of the hanger will be installed flush with the bottom of the girder bottom chord, a hanger that is much shorter than the bottom chord will induce tension perpendicular to the grain in the chord. Due to wood’s inherent weakness in perpendicular-to-grain tension, a hanger that is too short may limit the amount of load that can be transferred– to something less than the hanger’s published allowable load. Therefore, it isn’t enough to check whether the hanger fits on the bottom chord; the hanger must also cover enough depth of the chord to effectively transfer the load (or else the allowable hanger load may need to be reduced to the member’s allowable cross-grain tension limit).

Cross-grain tension is not a truss-specific issue, but because it is an explicit design provision in the truss design standard (TPI 1), it is a necessary consideration to mention in a discussion about truss hanger selection. In fact, proper detailing for cross-grain tension in different wood applications could be a future topic in and of itself.

Add to all this the specialty truss hangers that can carry two, three, four, and even five trusses framing into one location, and it is no wonder that there is an entire section in our catalog that is dedicated to truss hangers. Are there any other truss hanger needs that you would like to discuss? Please let us know in the comments below!