Three years ago, we created this blog post based on a technical support question we often receive about allowable fastener loads for ledgers to wood framing over gypsum board. Given that this is still a frequent question and a relevant topic, we decided to revisit the post and update it.

Drywall. Wall board. Sheetrock. Sackett Board? A product called Sackett Board was invented in the 1890s, which was made by plastering within wool felt paper. United States Gypsum Corporation refined Sackett Board for several years until 1916, when they developed a new method of producing boards with a single layer of plaster and paper. This innovation was eventually branded SHEETROCK®. More details about the history of USG can be found here.

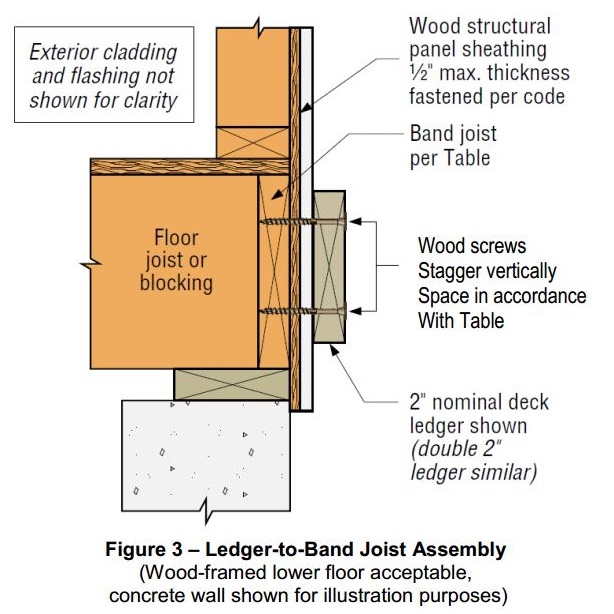

No matter what you call it, gypsum board is found in almost every type of construction. Architects use it for sound and fire ratings, while structural engineers need to account for its weight in our load calculations. A common technical support question we receive is for allowable fastener loads for ledgers to wood framing over gypsum board.

One method to evaluate a fastener spanning across gypsum board is to treat the gypsum material as an air gap. Technical Report 12, General Dowel Equations for Calculating Lateral Connection Values, is published by the American Wood Council.

TR12 has yield limit equations that allow a designer to account for a gap between the main member and side member of a connection. With a gap of zero (g=0), the TR12 equations provide the same results as the NDS yield limit equations.

The equations are fairly complex, but it should be intuitive that the calculated fastener capacity decreases with increasing gap. Engineers are often surprised to see a 40, 50, even 60% drop in fastener capacity with one layer of 5/8” gypsum board. So what else can you do?

Testing, of course! In So, What’s Behind a Screw’s Allowable Load? I discussed the methods used to load rate a proprietary fastener such as the Simpson Strong-Tie® Strong-Drive® SDS or SDW screws. To recap, ICC-ES Acceptance Criteria for Alternate Dowel Type Fasteners, AC233, allows you to calculate and do verification tests, or load rate based on testing alone. We develop our allowable loads primarily by testing, as the performance enhancing features and material optimizations in our fasteners are not addressed by NDS equations.

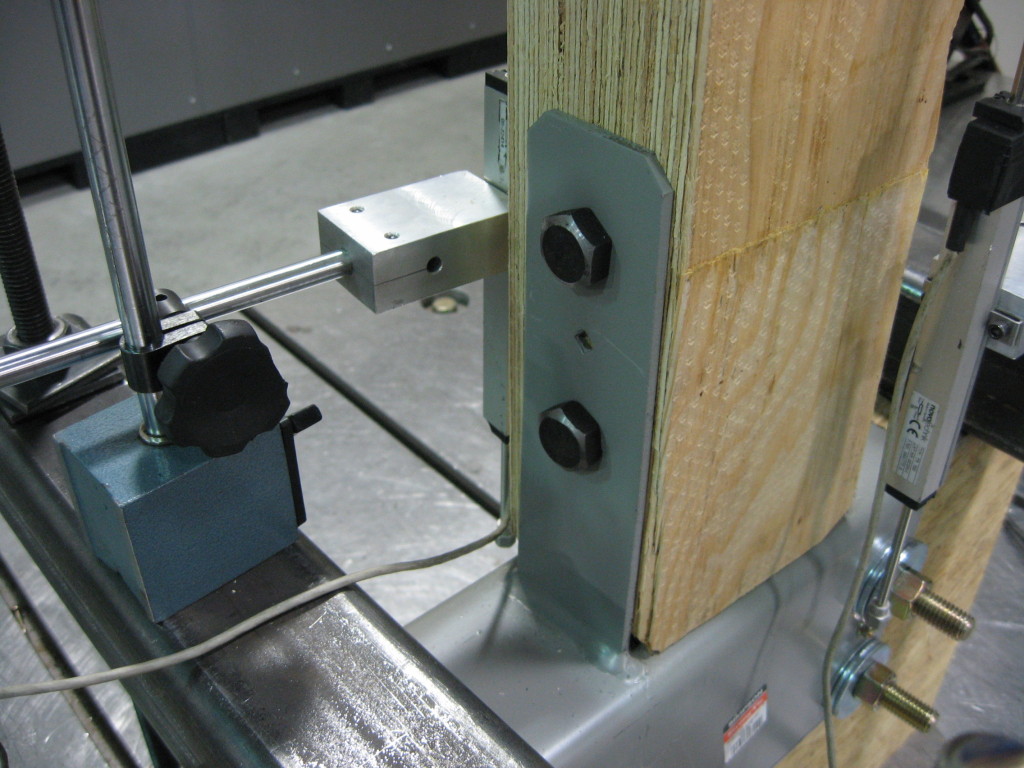

So to determine the performance of a fastener installed through gypsum board, we tested the fastener through gypsum board. This is easier to do if you happen to have a test lab with a lot of wood and fasteners in it. We did have to run down to the local hardware store to pick up gypsum board for the testing.

A full set of allowable loads for Strong-Drive SDWH and SDWS are available on strongtie.com. The information is given as single fastener shear values for engineered design, and also screw spacing tables for common ledger configurations. As much fun as writing spreadsheets to do the Technical Report 12 calculations is, having tabulated values based on testing is much easier.

Fastening Systems

In the fastener marketplace, Simpson Strong-Tie stands apart from the rest. Quality and reliability is our top priority.