Discover insights from Simpson Strong-Tie engineer Emily Morris Frazier, P.E., as she examines the evolution of moment frame construction over the past 150 years. She traces the transition from early rivet and angle connections to the prevalent use of welded moment frames in seismic zones. Emily addresses the challenges that emerged after significant earthquakes, which spurred the development of prequalified connections to boost safety and performance. She highlights the ongoing advancements in design strategies that aim to enhance the resilience of modern structures.

Tag: steel

Using the Edge-Tie™ System to Create Curved Façades in Steel Construction

Curved façades can help create architecturally appealing steel structures and may even reduce the effects of wind loading. However, careful coordination is needed between engineers, contractors and glaziers when locating façade attachments. Providing adequate tolerances and avoiding field fixes can prove to be more challenging for curved façades than for conventional rectangular ones.

Learn New Design Methods to Enclose Buildings Faster Webinar Q&A

In this post, we follow up on our October webinar, New Design Methods to Enclose Buildings Faster, by answering some of the interesting questions raised by attendees.

During the webinar, we discussed new design methods and solutions for curtain-wall and cladding connections and how they can maximize efficiency and resiliency throughout the construction process. In case you could not join our discussion, you can watch the on-demand webinar and earn PDH and CEU credits here.Continue Reading

Questions Answered: Yield-Link® Connection for Steel Construction

In this post, we follow up on our May 2 webinar, Seismic Resilience and Risk Assessment of the Yield-Link® Connection for Steel Construction, by answering some of the interesting questions raised by the attendees.

During the webinar, we discussed how to achieve seismic resiliency in steel construction with our Yield-Link connection for steel special moment frames and the Seismic Performance Prediction Program (SP3) by Haselton Baker Risk Group. In case you weren’t able to join our discussion, you can watch the on-demand webinar and earn PDHs and CEUs here.

As with our previous webinars, we ended with a Q&A session for the attendees. Jeff Ellis, our Director of Codes and Compliance, and Curt Haselton and Jared Debock, from Haselton Baker Risk Group, answered as many questions as they could in the time allowed. Now we are back to recap some of the more commonly asked questions and their answers. If you’re interested in seeing the full list of questions, click here.

Continue Reading

NASCC 2018: Debuting Our Newest Yield Link Connection

This year the NASCC (North American Steel Construction Conference) will be in Baltimore, Maryland. The conference is the annual educational and networking event for the structural steel industry, which attracts attendees and exhibitors from all over the world. With more than 130 sessions this year, the conference will provide attendees the opportunity to learn the latest in research, design, technology and best practice in the steel industry.

Continue Reading

How Heat Treating Helps Concrete Anchoring Products Meet Tougher Load Demands

There’s a saying in Chicago, “If you don’t like the weather, just wait fifteen minutes.” That’s especially true in the spring, when temperatures can easily vary by over 50° from one day to the next. As the temperature plunges into the blustery 30s one evening following a sunny high in the 80s, I throw my jacket on over my T-shirt, and I’m reminded that large swings in temperature tend to bring about changes in behavior as well. This isn’t true just with people, but with many materials as well, and it brings to mind a thermal process called heat treating. This is a process that is used on some concrete anchoring products in order to make them stronger and more durable. You may have heard of this process without fully understanding what it is or why it’s useful. In this post, I will try to scratch the surface of the topic with a very basic overview of how heat treating is used to improve the performance of concrete anchors.Continue Reading

Hydrogen Embrittlement in High-Strength Steels

The use of high-strength steels in anchors and fasteners is not unusual in the construction world. For example, high-strength threaded rods are often used to reduce the number of mild-steel rods that would be required to meet a design load for an adhesive anchor. High-strength steel is essential to the function of some fasteners, such as self-drilling and self-tapping screws.

However, for anchors and fasteners, there are limits to what can be accomplished by increasing steel strengths due to a phenomenon known as hydrogen embrittlement. Hydrogen embrittlement is well known by anchor and fastener manufacturers, but it is not widely known by structural engineers. The purpose of this blog post is to provide an overview of this important subject and some insight into one reason why steels used in construction anchors and fasteners have upper strength limits.

What is hydrogen embrittlement?

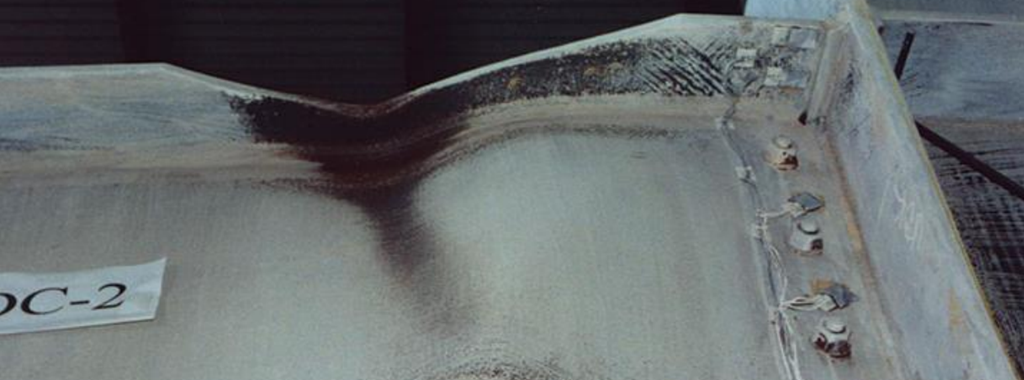

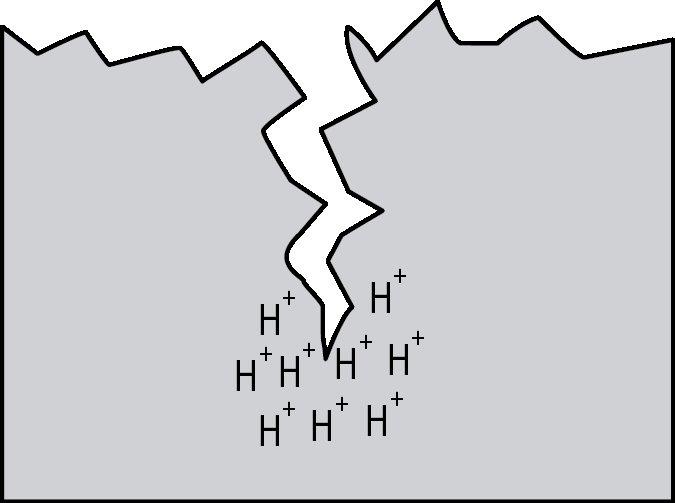

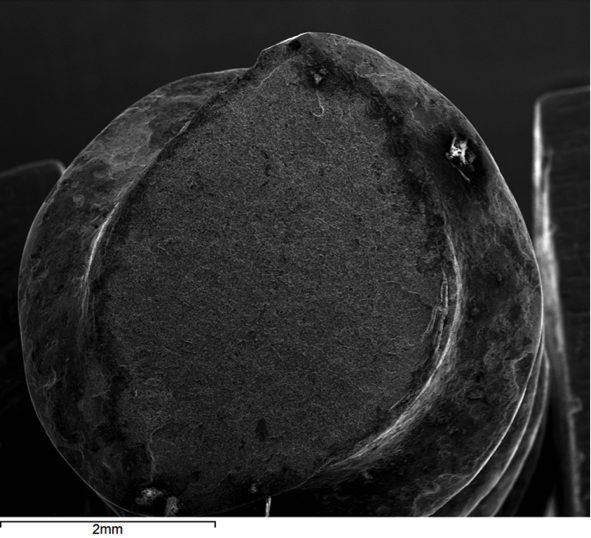

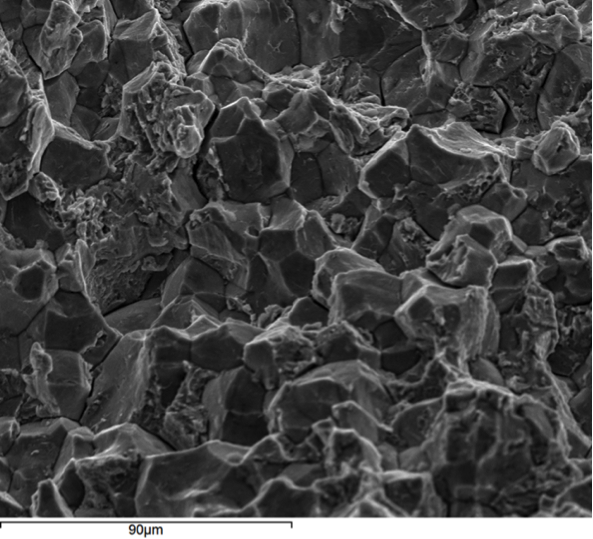

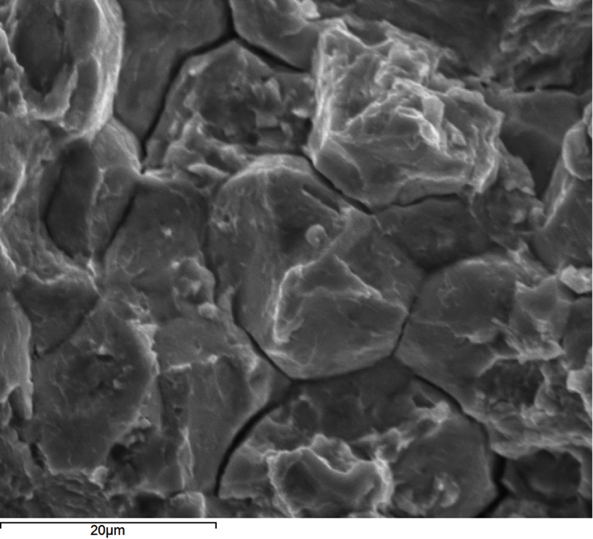

Hydrogen embrittlement is a significant permanent loss of strength that can occur in some steels when hydrogen atoms are present in the steel and stress is applied. Embrittlement occurs as hydrogen atoms migrate to the region of highest stress and cause microcracks. When a crack forms, the hydrogen then migrates to the tip of the crack (Figure 1) and causes continued crack growth until the effective fastener cross-section is so reduced that the remaining cross-section is overloaded and the fastener fails. Figures 2, 3 and 4 show a failure plane and coarse granular morphology and intergranular cracks (dark lines in Figures 3 and 4). These failures occur suddenly, without warning, after the fastener or rod has been loaded for a period of time.

All three of the aforementioned conditions must be present for hydrogen embrittlement to occur:

- A steel that is susceptible to hydrogen embrittlement

- Atomic hydrogen (H+ ions, not H2 gas)

- Stress, such as from tightening or applied loads

If an application involves these, then there is a possibility of hydrogen embrittlement and fastener failure. The possibility of and time to failure depend on the degree of each of these conditions. Therefore, the level of concern should depend on the degree to which the Designer expects all three of these conditions to be present in the application.

What steels are sensitive to hydrogen embrittlement?

A fastener’s susceptibility to hydrogen embrittlement increases with elevated tensile strength or hardness. It is generally accepted that good-quality fasteners with an actual (not specified) Rockwell C scale hardness of less than 38 (tensile strength of less than approximately 170,000 psi) are not ordinarily susceptible to hydrogen embrittlement. Fastener manufacturers often establish lower hardness limits as an extra margin of safety for variability that may occur in production.

When are hydrogen atoms (H+) present?

Hydrogen atoms can be introduced into a fastener from manufacturing or from the service environment.

Sources of hydrogen from manufacturing:

Hydrogen can be present in the steel-making process, but the amount present in good-quality steel is below the level that causes problems. The most common way that hydrogen is introduced during anchor and fastener manufacturing is from the cleaning and coating processes. These processes often utilize acids that produce hydrogen. Compounding this problem is that many popular coatings like zinc plating (ASTM B633) and hot-dip galvanizing (ASTM A153) create a barrier around the fastener that does not allow hydrogen to easily diffuse out of the fastener. Some coatings, like mechanical galvanizing (ASTM B695), do have sufficient porosity that hydrogen can diffuse through the coating at room temperature.

Manufacturers most commonly manage internal hydrogen sources by minimizing cleaning time and by baking plated fasteners after coating for a number of hours to help diffuse hydrogen through the coating and out of the fastener. In some cases, mechanical cleaning and alkaline cleaning are used to prevent hydrogen from being introduced.

In cases where internal hydrogen is not properly managed in the manufacturing process, failure usually occurs quickly, within 48 hours of fastener installation.

External sources of hydrogen:

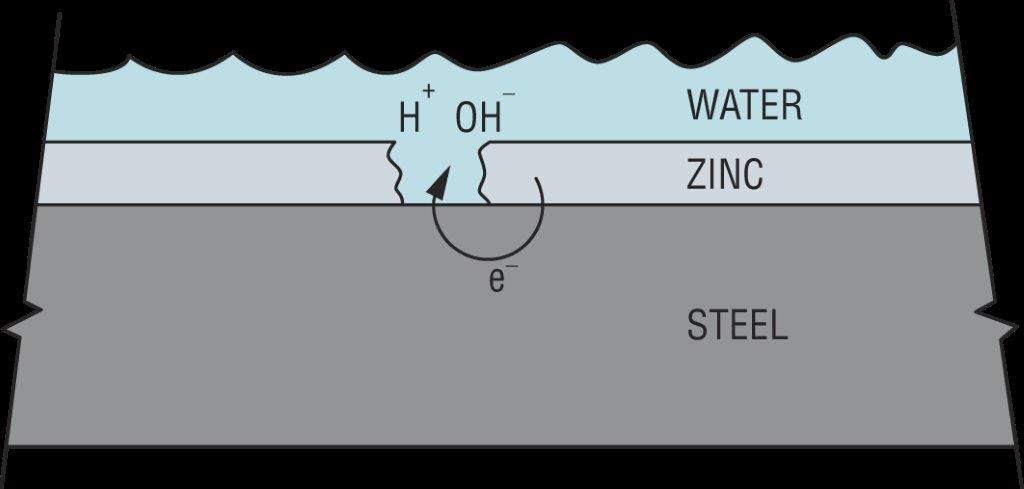

Hydrogen can also be introduced from the service environment. Zinc coatings galvanically protect steel from corrosion in damp or wet service environments. However, this process results in an electric current being passed through the water (H2O) to produce hydrogen (H+) and hydroxide (OH–) ions as shown in Figure 5. Since this process requires corrosion to generate the hydrogen, failures from externally generated hydrogen usually take much longer to occur than when internal hydrogen is the cause. Steel failure from externally generated hydrogen can take anywhere from weeks to years.

How much stress is too much stress?

Fortunately, for products that require very high-strength steels, hydrogen embrittlement risk diminishes, even for sensitive steels, as applied loads are reduced. For such products there are a number of complex tests that fastener manufacturers utilize in development and quality control to verify that the risk of hydrogen embrittlement is controlled for the intended application at the rated loads.

Closing thoughts

As illustrated in the discussion above, hydrogen embrittlement can be a serious concern for high-strength anchors and fasteners. A Designer should exercise great care to guard against the sudden brittle steel failure that this phenomenon can produce. There are a number of good practices to follow in this regard:

- Do not utilize exotic high-strength steels with actual tensile strengths greater than 170,000 psi (Rockwell C-scale hardness of 38) without carefully considering hydrogen embrittlement risk. Note that actual tensile strength may be higher than specified tensile strengths.

- Ensure that quality sources of high-strength fasteners are specified. High-quality manufacturers have design and manufacturing practices in place to guard against hydrogen embrittlement.

- Use discretion in selecting very high-strength fasteners for corrosive applications since these conditions often produce hydrogen through the galvanic process.

Connectors and Fasteners in Fire-Retardant-Treated Wood

In any given year, Simpson Strong-Tie fields several questions about the use of our connectors and fasteners with pressure-treated fire-retardant wood products. Most often asked is whether this application meets the building code requirements for Type III construction, and whether there is a legitimate concern about corrosion. While there haven’t been any specific discussions on this topic in the SE Blog, there have been related discussions surrounding sources of corrosion, such as: Corrosion: The Issues, Code Requirements, Research and Solutions, Corrosion in Coastal Environments, Deck Fasteners – Deck Board to Framing Attachments. This post will explore several resources that we hope will enable you to make an informed decision about which type of pressure-treated Fire-Retardant-Treated Wood (FRTW) to choose for use with steel fasteners and connectors.

One factor contributing to the frequency of these questions is the increased height of buildings now being constructed. With increased height, there is a requirement for increased fire rating. To meet the minimum fire rating for taller buildings, the building code requires noncombustible construction for the exterior walls. As an exception to using noncombustible construction, the 2015 International Building Code (IBC®) section 602.3 allows the use of fire-retardant wood framing complying with IBC section 2303.2. This allows the use of wood-framed construction where noncombustible materials would otherwise be required.

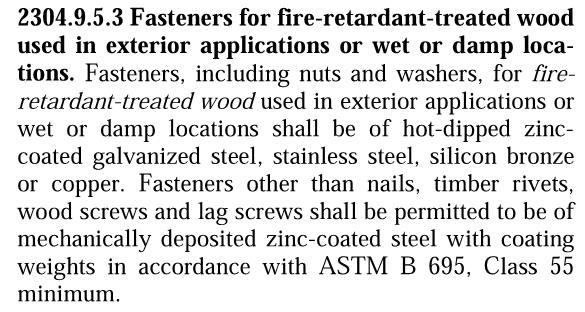

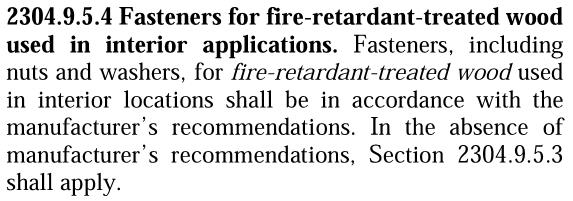

In the 2009 IBC, Section 2304.9.5, “Fasteners in preservative-treated and fire-retardant-treated wood,” was revised to include many subsections (2304.9.5.1 through 2304.9.5.4) dealing with these wood treatments in various types of environmental applications. Section 2304.9.5.3 addressed the use of FRTW in exterior applications or wet or damp locations, and 2304.9.5.4 addressed FRTW in interior applications. These sections carried over to the 2012 IBC, and were moved to Section 2304.10.5 in the 2015 IBC. FRTW is listed in various other sections within the code. For more information about FRTW within the code (e.g., strength adjustments, testing, wood structural panels, moisture content), the Western Wood Preservers Institute has a couple of documents to consult: 2009 IBC Document and 2013 CBC Document. They also have a number of different links to various wood associations.

As shown in Figure 1 below, fasteners (including nuts and washers) used with FRTW in exterior conditions or where the wood’s service condition may include wet or damp locations need to be hot-dipped zinc-coated galvanized steel, stainless steel, silicon bronze or copper. This section does permit other fasteners (excluding nails, wood screws, timber rivets and lag screws) to be mechanically galvanized in accordance with ASTM B 695, Class 55 at a minimum. As shown in Figure 2, fasteners (including nuts and washers) used with FRTW in interior conditions need to be in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations, or, if no recommendations are present, to comply with 2304.9.5.3.

In Type III construction where the exterior walls may be FRTW in accordance with 2012 IBC Section 602.3, one question that often comes up is whether the defined “exterior wall” should comply with Section 2304.9.5.3 or 2304.9.5.4. While there are many different views on this point, it is our opinion at Simpson Strong-Tie that Section 2304.9.5.4 would apply to the exterior walls. Since the exterior finishes of the building envelope are intended to protect the wood and components within its cavity from exterior elements such as rain or moisture, the inside of the wall would be dry.

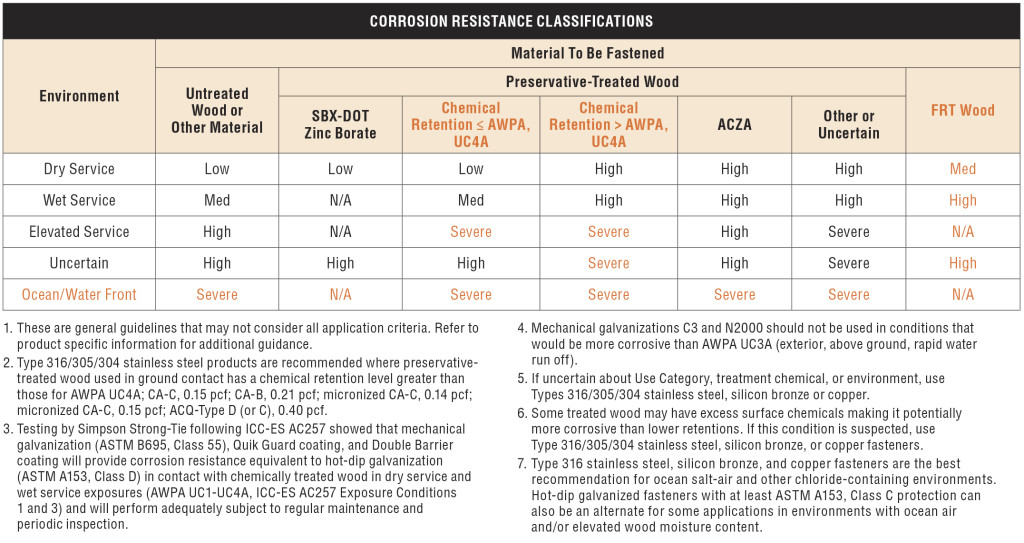

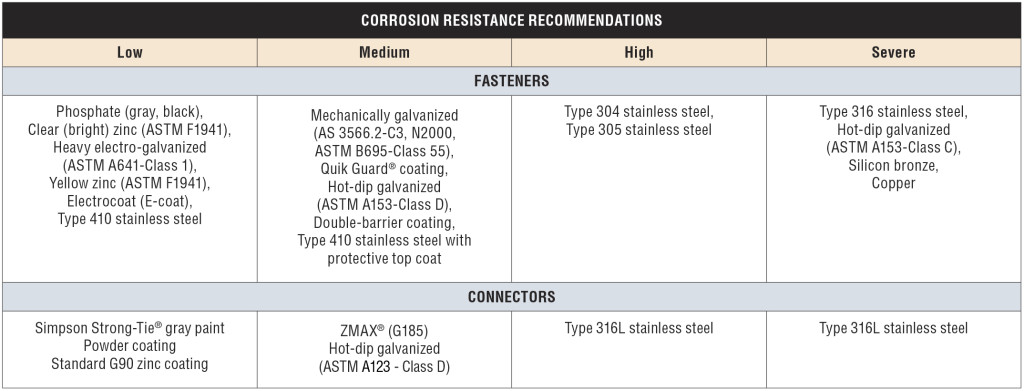

There are many FRTW product choices on the market; take a look at the American Wood Council’s list of treaters. Unlike the preservative-treated wood industry, however, the FRTW industry involves proprietary formulations and retentions. As a result, Simpson Strong-Tie has not evaluated the FRTW products. In our current connector and fastener catalogs, C-C-2015 Wood Connector Construction and C-F-14 Fastening Systems, you will find a newly revised Corrosion Resistance Classifications chart, shown in Figure 3 below, which can be found on page 15 in each catalog. The FRTW classification has been added to the chart in the last column. The corrosion protection recommendations for FRTW in various environmental applications is set to medium or high, corresponding to a number of options for connectors and fasteners as shown in the Corrosion Resistance Recommendations chart, shown in Figure 4. These general guideline recommendations are set to these levels for two reasons: (1) there are unknown variations of chemicals commercially available on the market, and (2) Simpson Strong-Tie has not conducted testing of these treated wood components.

The information above is not the only information readily available. There are many different tests that can be done on FRTW, as noted in the Western Wood Preservers Institute’s document. One such test for corrosion is Military Specification MIL-1914E, which deals with lumber and plywood. Another is AWPA E12-08, Standard Method of Determining Corrosion of Metals in Contact with Treated Wood. Manufacturers of FRTW products who applied for and received an ICC-ES Evaluation Report must submit the results of testing for their specific chemicals in contact with various types of steel. ICC-ES Acceptance Criteria 66 (AC66), the Acceptance Criteria for Fire-Retardant-Treated Wood, requires applicants to submit information regarding the FRTW product in contact with metal. The result is a section published in each manufacturer’s evaluation report (typically Section 3.4) addressing the product use in contact with metal. Many published reports contain similar language, such as “The corrosion rate of aluminum, carbon steel, galvanized steel, copper or red brass in contact with wood is not increased by (name of manufacturer) fire-retardant treatment when the product is used as recommended by the manufacturer.” Structural engineers should check the architect’s specification on this type of material. Product evaluation reports should also be checked to ensure proper specification of hardware and fastener coatings to protect against corrosion. Each evaluation report also contains the applicable strength adjustment factors, which vary from one product to another.

Selecting the proper FRTW product for use in your building is crucial. There are many different options available. Be sure to select a product based on the published information and to communicate that information to the entire design team. Evaluation reports are a great source of information because the independently witnessed testing of manufacturers has been reviewed by the agency reviewing the report. Finally, understanding FRTW chemicals and their behavior when in contact with other building products will ensure expected performance of your structures.

What has been your experience with FRTW? What minimum recommendations do you provide in your construction documents?

But I Don’t Design Cold-Formed Steel…

For the first half-dozen years of my professional career, my experience with cold-formed steel (CFS) consisted of sizing studs for non-structural walls and red-marking the bracing details on architectural plans. When the dotcom bubble burst, my firm needed to shift its focus from high-tech commercial and industrial to more multifamily design work. Several developers we worked with built with CFS, so in addition to designing condominiums instead of cleanrooms, I was designing CFS.

Less than 10% of engineers have any exposure to CFS design as part of their undergraduate education. OK – so this is based on an informal survey of about 50 colleagues, but I suspect if I were to hire a market research firm for lots of money, I’d pretty much get the same response.