Specification of Concrete Anchors

The 2012 IBC and its Referenced Standard, ACI 318-11, is the first to mandate that contract documents specifically address installation, inspections and design parameters of concrete anchorage. For this reason, the specification of anchors in drawing details alone is impractical. To fully and effectively address these code mandates, concrete anchorage is more practically specified in both drawing detail(s) and the General

Structural Notes or specifications of the contract documents. The drawing detail(s) would typically call out the anchor type, material specification, diameter, and embedment depth. The General Structural Notes or specifications would include the name of the qualified anchor(s) and address the installation, inspections and design parameter requirements of ACI 318-11.

The following sections of ACI 318-11 discuss the contract document requirements for concrete anchorage:

The commentary in ACI 318-11, RD.9.1 discusses the sensitivity of anchor performance to proper installation. It emphasizes the importance of qualified installers for all anchors, and compliance with the Manufacturer’s Printed Installation Instructions (MPII) for post-installed anchors. Training is required for adhesive anchor installers per ACI 318-11 D.9.1. Simpson Strong-Tie Co. Inc. provides free installer training by experienced Technical Sales Representatives for our adhesive, mechanical and specialty anchors. Contact us at 1-800-999-5099. Special inspection and proof loading are addressed in ACI 318-11 D.9.2

and D.9.2.1.

Per the section above, anchor installation requires inspection per Section D.9.2. In addition, the design parameters for adhesive anchors are required to be specified in the contract documents. An explanation of the design parameters listed in ACI 318-11 D.9.2.1 is provided below:

- Proof loading where required in accordance with ACI 355.4. Proof loading is only required for adhesive anchors loaded in tension in which the inspection level chosen for the adhesive anchor design is “Continuous” (Ref. ACI 355.4 Section 10.4.6). Selecting “Continuous Inspection” can result in a higher “Anchor Category,” which in turn results in a higher strength reduction factor, φ. Reference Section 13.3.4 of ACI 355.4 for the minimum requirements of the proof loading program, where required. The Design Professional is responsible for performing the quantity, the duration of

the applied load, and the proof load to which the anchors will be tested. These parameters will be specific to the anchor design conditions. - Minimum age of concrete at time of anchor installation. Per ACI 318 D.2.2, adhesive anchors must be installed in concrete having a minimum age of 21 days at time of anchor installation. Simpson Strong-Tie® has performed in-house testing of SET-XP®, AT-XP®, and ET-HP® adhesive anchors installed in 7-day- and 14-day-old concrete. The results of testing are published in an engineering letter (L-A-ADHGRNCON15.pdf), which can be viewed and downloaded at www.strongtie.com.

- Concrete temperature range. This is the in-service temperature of the concrete into which the adhesive anchor is installed. Temperature Ranges are categorized as 1, 2 or 3. Some manufacturers use A, B, or C as the category designations. Each Temperature Range category has a maximum short-term concrete temperature and a maximum long-term concrete temperature. Short-term concrete temperatures are those that occur over short intervals (diurnal cycling). Long-term concrete temperatures are constant temperatures over a significant time period.

- Moisture condition of concrete at time of installation. Moisture conditions, as designated by ACI 355.4, are “dry,” or “water-saturated.” Moisture condition impacts the characteristic bond stress of an adhesive.

- Type of lightweight concrete, if applicable.

- Requirements for hole drilling and preparation. These requirements are specific to the adhesive, and are described in the Manufacturer’s Printed Installation Instructions (MPII). Reference to the MPII in the contract documents is sufficient.

Adhesive anchors installed in a horizontal or upwardly inclined orientation that resist sustained tension loads require a “certified” installer.

A certification program has been established by ACI/CRSI. Installers can obtain certification by successful completion of this program. Contact your local ACI or CRSI chapter for more information. Other means of certification are permitted, and are the responsibility of the licensed design professional.

The installation of adhesive anchors in a horizontal or upwardly inclined orientation presents unique challenges to the installer. Simply put, the effects of gravity for these applications make it difficult to prevent air bubbles and voids, which can limit full adhesive coverage of the insert (threaded rod or reinforcing bar). Due to the increased installation difficulty of these anchors, they are required to be continuously inspected by a certified special inspector.

Suggested General Structural Notes or specifications for post-installed anchors can be viewed and downloaded at here, or contact a Simpson Strong-Tie® representative for help with your post-installed General Structural Notes or specifications.

Simpson Strong-Tie Suggested General Note for Anchor Products

Post-Installed Anchors into Concrete, Masonry and

Steel and Cast-in-Place Anchors into Concrete

The below products are the design basis for this project. Substitution requests for products other than those listed below may be submitted by the contractor to the Engineer-of-Record (EOR) for review. Substitutions will only be considered for products having a code Report recognizing the product for the appropriate application and project building code. Substitution requests shall include calculations that demonstrate the substituted product is capable of achieving the equivalent performance values of the

design basis product. Contractor shall contact manufacturer’s representative (800-999-5099) for product installation training and a letter shall be submitted to the EOR indicating training has taken place. Refer to the building code and/or evaluation report for special inspections and proof load requirements.

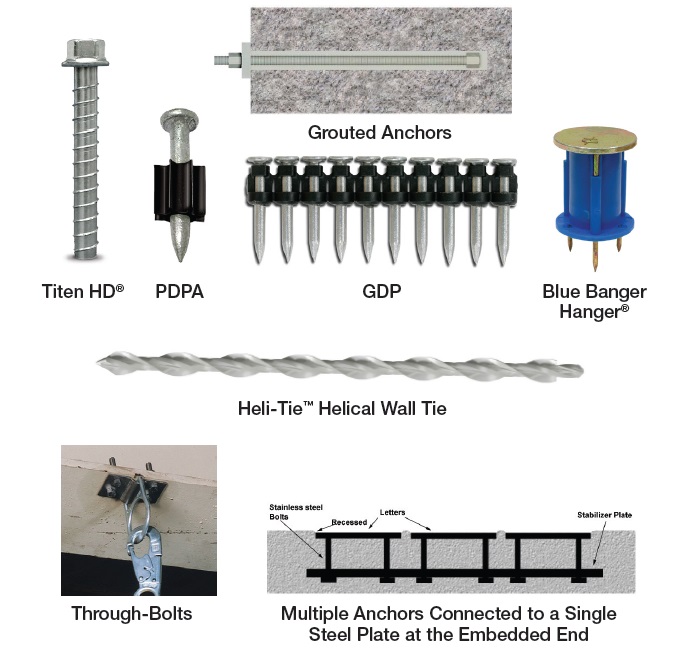

- For anchoring into cracked and uncracked concrete

a) Mechanical anchors shall have been tested in accordance with ACI 355.2 and/or ICC-ES AC193 for cracked concrete and seismic applications. Pre-approved products include:

i. Simpson Strong-Tie® Strong-Bolt® 2 (ICC-ES ESR-3037)

ii. Simpson Strong-Tie® Titen HD® (ICC-ES ESR-2713)

iii. Simpson Strong-Tie® Torq-Cut® (ICC-ES ESR-2705)

iv. Simpson Strong-Tie® Titen HD® Rod Hanger (ICC-ES ESR-2713)

v. Simpson Strong-Tie® Blue Banger Hanger® (ICC-ES ESR-3707, except roof deck insert)

b) Adhesive anchors shall have been tested in accordance with ACI 355.4 and/or ICC-ES

AC308 for cracked concrete and seismic applications. Adhesive anchors shall be installed

by a certified adhesive anchor installer where designated on the contract documents.

Pre-approved products include:

i. Simpson Strong-Tie® AT-XP® (IAPMO-UES ER-263)

ii. Simpson Strong-Tie® SET-XP® (ICC-ES ESR-2508)

III. Simpson Strong-Tie® ET-HP® (ICC-ES ESR-3372)