Who likes red rust? No one I know! How do we avoid corroding of fasteners? Corrosion can be controlled or eliminated by providing a corrosion-resistant base metal or a protective finish or coating that is capable of withstanding the exposure environment. When fasteners get corroded, they not only look bad from outside but can also lose their load capacity. To ensure continued fastener performance, we have to control for corrosion. This blog focuses on evaluating the corrosion resistance of the fasteners.

What does the building code specify?

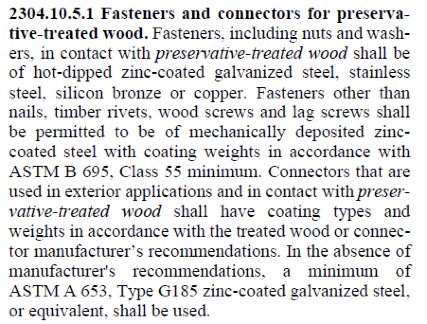

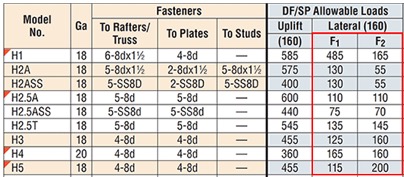

For use in preservative-treated wood, the IBC-2015 specifies fasteners that are hot-dipped galvanized, stainless steel, silicon bronze or copper. Section 2304.10.5.1 of IBC-2015 (Figure 1) covers fastener and connector requirements for preservative-treated wood (chemically treated wood). While chemically treated wood is part of the corrosion hazard, it is not the whole corrosion hazard. Weather exposure, airborne chemicals and other environmental conditions contribute to the corrosion hazard for metal hardware. In addition, the main issue with the code-referenced requirements for fasteners and connectors used with preservative-treated wood is that not all preservative treatments deliver the same corrosion hazard and not all fasteners can be hot-dip galvanized.

What if we want to use an alternative base material or coating for fasteners?

How do we evaluate the corrosion resistance of the alternative material or coating? The codes do not provide test methods to evaluate alternate materials and coatings. However, the International Code Council–Evaluation Service (ICC-ES) developed acceptance criteria to evaluate alternative coatings that are not code recognized for use in different environments. The purpose of acceptance criteria ICC-ES AC257, Acceptance Criteria for Corrosion-Resistant Fasteners and Evaluation of Corrosion Effects of Wood Treatment Chemicals, is twofold: (1) to establish requirements for evaluating the corrosion resistance of fasteners that are exposed to wood-treatment chemicals, weather and salt corrosion in coastal areas; and (2) to evaluate the corrosion effects of wood-treatment chemicals. In this blog post, we will concentrate on the evaluation of corrosion resistance of fasteners. The criteria provide a protocol to evaluate the corrosion resistance of fasteners where hot-dip galvanized fasteners serve as a performance benchmark. The fasteners evaluated by these criteria are nails or screws that are exposed directly to wood-treatment chemicals and that may be exposed to one or more corrosion accelerators like high humidity, elevated temperatures, high moisture or salt exposure.

The fasteners may be evaluated for any of the four exposure conditions:

- Exposure Condition 1 with high humidity. This test can be used to evaluate fasteners that could be exposed to high humidity. Typical applications that fall under this category are treated wood in dry-use applications.

- Exposure Condition 2 with untreated wood and salt water. This test can be used to evaluate fasteners that are above ground but exposed to coastal salt exposure.

- Exposure Condition 3 with chemically treated wood and moisture. This test covers all the general construction applications.

- Exposure Condition 4 with chemically treated wood and salt water. Typical applications include coastal construction applications.

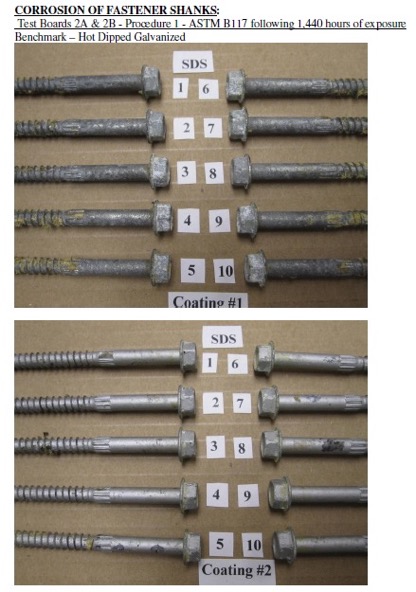

Depending on the exposure condition being used for fastener evaluation, the fasteners are installed in wood that could be either chemically treated or untreated. Then the wood and the fasteners are placed in the chamber and artificially exposed to the evaluation environment. Two types of test procedures are to be completed for exposure condition 2 through 4. The purpose of these tests is not to predict the corrosion resistance of the coatings being evaluated, but to compare them to fasteners with the benchmark coating (ASTM A153, Class D) in side-by-side exposure to the accelerated corrosion environment.

ASTM B117 Continuous Salt-Spray Test

ASTM B117 is a continuous salt-spray test. For Exposure Condition 3, distilled water is used instead of salt water. The fasteners are continuously exposed to either moisture or salt spray in this test, and the test is run for about 1,440 hours after which the fasteners are evaluated for corrosion. This is an accelerated corrosion test that exposes the fasteners to a corrosive attack so the corrosion resistance of the coatings can be compared to a benchmark coating (hot-dip galvanized).

ASTM G85, Annex A5

The second test is ASTM G85, Annex A5 which is a cyclic test with alternate wet and dry cycles. The cycles are 1-hour dry-off and 1-hour fog alternatively. This is a cyclic accelerated corrosion test and relates more closely to real long-term exposure. This test is more representative of the actual environment than the continuous salt-spray test. As in the ASTM B117 test, the fasteners along with the wood are exposed to 1,440 hours, after which the corrosion on the fasteners is evaluated and compared to fasteners with the benchmark coating.

Test Method and Evaluation

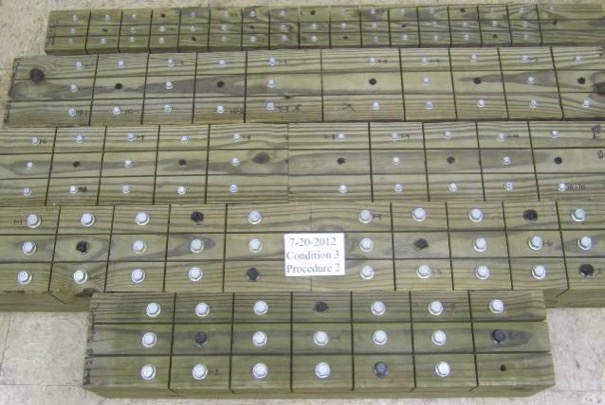

The test process involves installing 10 benchmark fasteners along with 10 fasteners for each alternative coating being evaluated. The fasteners are arranged in the wood with a spacing of 12 times the fastener diameter between the fasteners. A kerf cut is provided in the wood between the fasteners to isolate the fasteners as shown in Figure 2 and to ensure elevated moisture content in the wood surrounding the fastener shank. The moisture and retention levels of the wood are measured, and the fasteners are then installed in the chamber as shown in Figure 3 and exposed to the designated condition. The test is run for the period specified, after which the fasteners are removed, cleaned and compared to the benchmark for corrosion evaluation. Figure 4 shows the wood and fastener heads after 1,440 hours (60 days). The heads and shanks of the fasteners are visually graded for corrosion in accordance with ASTM D610. If the alternate coating performs equivalent to or better than the benchmark coating — that is, if the corrosion is no greater than in the benchmark — then the coating has passed the test and can be used as an alternative to the code-approved coating. Figure 5 shows the benchmark and alternative fasteners that are removed from the chamber after 1,440 hours.

As you can see, the alternative coatings have to go through extended and rigorous testing and evaluation as part of the approval process before being specified for any of the fasteners. Some alternative coatings provide even better corrosion resistance than the code recognized options. Sometimes, also, the thickness of these alternative coatings may be smaller than the thick coating required for hot-dip galvanized parts. Some of our coatings, such as the Double-Barrier coating, the Quik Guard® coating and the ASTM B695 Class 55 Mechanically Galvanized have gone through this rigorous testing and have been approved for use in preservative-treated wood in the AC257 Exposure Conditions 1 and 3. In addition, these coatings have been qualified for use with chemical retentions that are typical of AWPA Use Category 4A – General Ground Contact. No salt is found in AC257 Exposure Conditions 1 and 3. Please refer to our Fastener Systems Catalog, C-F-14, pages 13–15 for corrosion recommendations and pages 16–17 for additional information on coatings.

What do you look for specifically in a fastener? Do you have a preference for a certain coating type or color? Let us know in the comments below!

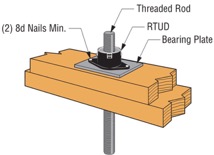

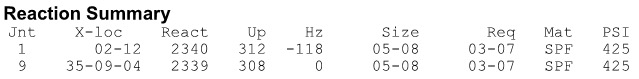

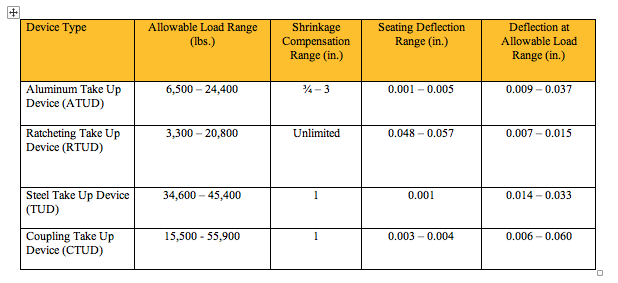

The most cost-effective Simpson Strong-Tie shrinkage compensation device is the RTUD. This device has the smallest number of components and allows the rod unlimited travel through the device. It is ideal at the top level of a rod system run or where small rod diameters are used. Simpson Strong-Tie RTUDs can now accommodate 5/8″ (RTUD5) and ¾” (RTUD6) diameter rods.

The most cost-effective Simpson Strong-Tie shrinkage compensation device is the RTUD. This device has the smallest number of components and allows the rod unlimited travel through the device. It is ideal at the top level of a rod system run or where small rod diameters are used. Simpson Strong-Tie RTUDs can now accommodate 5/8″ (RTUD5) and ¾” (RTUD6) diameter rods.