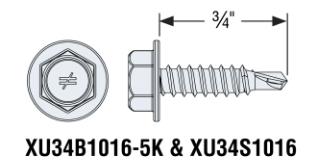

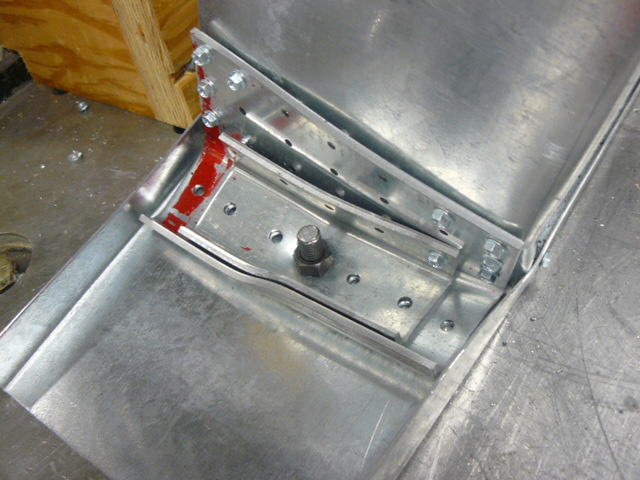

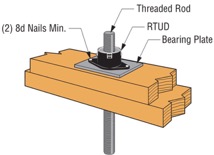

Over the weekend, I had the pleasure of watching my daughter in her cheer competition. I was amazed at all the intricate detail they had to remember and practice. The entire team had to move in sync to create a routine filed with jumps, tumbles, flyers and kicks. This attention to detail reminded me of the new ratcheting take-up device (RTUD) that Simpson Strong-Tie has just developed to accommodate 5/8″ and ¾” diameter rods. The synchronized movement of the internal inserts allows the rod to move smoothly through the device as it ratchets. The new RTUDs are cost effective and allow unlimited movement to mitigate wood shrinkage in a multi-story wood- framed building. When designing such a building, the Designer needs to consider the effect of shrinkage and how to properly mitigate it.

Our SE blog post on Continuous Rod Restraint Systems for Multi-Story Wood Structures explained the importance of load path and the effects of wood shrinkage. This week’s blog post will focus on the importance of mitigating the shrinkage that typically occurs in multi-story light-frame buildings.

Shrinkage is natural in a wood member. As moisture reaches its equilibrium in a built environment, the volume of a wood member decreases. The decrease in moisture causes a wood-framed building to shrink.

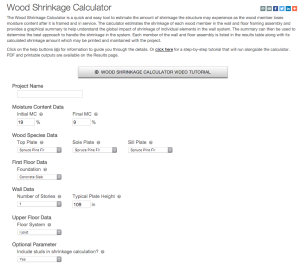

The IBC allows construction of light-framed buildings up to 5 and 6 stories in the United States and Canada respectively. Based on the type of floor framing system, the incremental shrinkage can be up to ¼” or more per floor. In a 5-story building, that can add up to 1-¼” or more and possibly double that when construction settlement is included.

The Simpson Strong-Tie Wood Shrinkage Calculator is a perfect tool to determine the total shrinkage your building can experience.

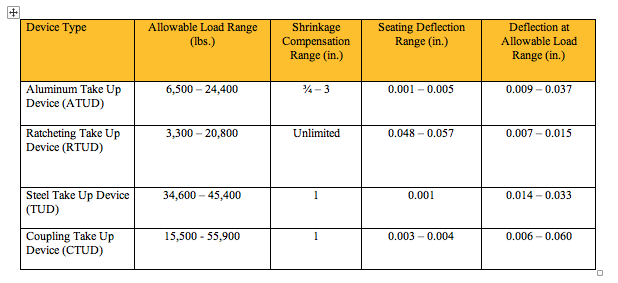

In order to accommodate the shrinkage that occurs in a multi-story wood-framed building, Simpson Strong-Tie offers several shrinkage compensating devices. These devices have been tested per ICC-ES Acceptance Criteria 316 (AC316) and are listed under ICC-ES ESR-2320 (currently being updated for the new RTUD5, RTUD6, and ATUD9-3).

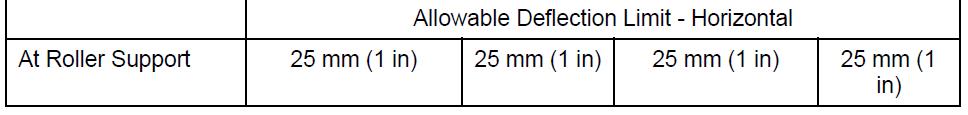

AC316 limits the rod elongation and device displacement to 0.2 inches between restraints in shearwalls. This deflection limit is to be used in calculating the total lateral drift of a light-framed wood shearwall.

The 0.2-inch allowable limit prescribed in AC316 is important to a shearwall’s structural ability to transfer the necessary lateral loads through the structure below to the foundation level. This limit assures that the structural integrity of the nails and sill plates used to transfer the lateral loads through the shearwalls is not compromised during a seismic or wind event. Testing has shown that sill plates can crack when excessive deformation is observed in a shearwalls. Nails have also been observed to pull out during testing. Additional information on this can be found here.

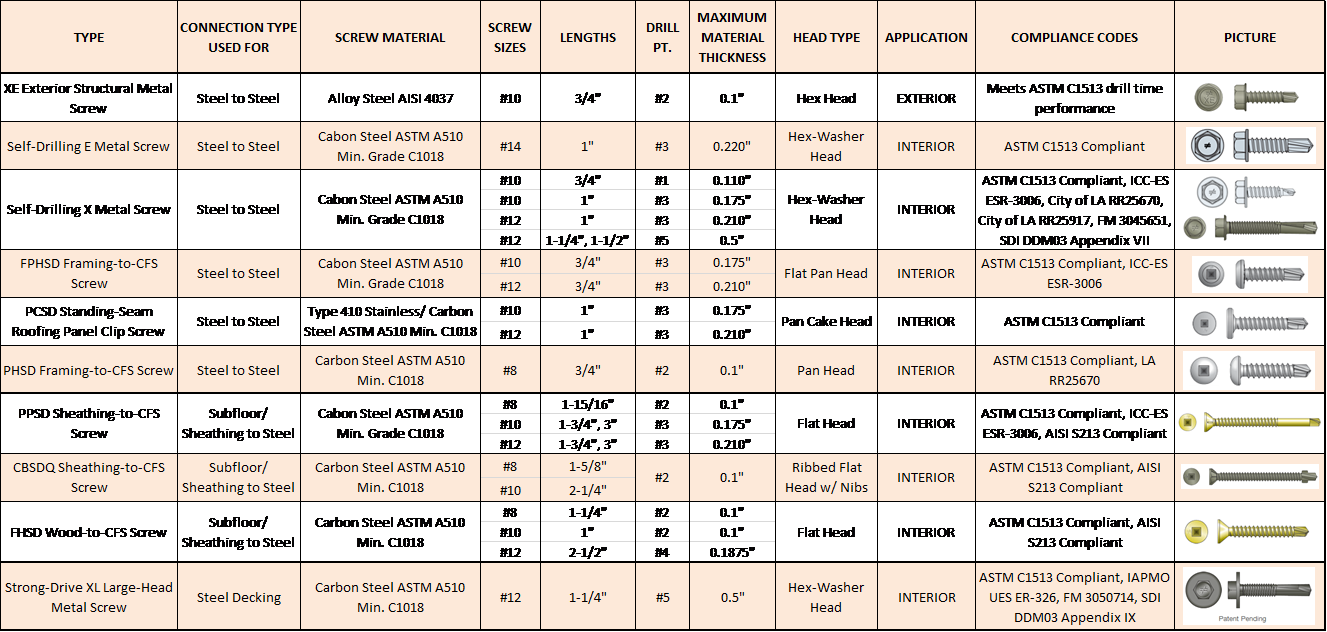

In AC316, 3 types of devices are listed.

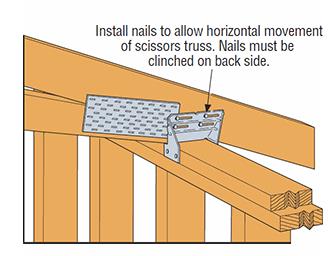

- Compression-Controlled Shrinkage Compensating Device (CCSCD): This type of device is controlled by compression loading, where the rod passes uninterrupted through the device. Simpson Strong-Tie has several screw-type take-up devices, such as the Aluminum Take-Up Device (ATUD) and the Steel Take-Up Device (TUD), of this type.

-

Tension-Controlled Shrinkage Compensating Device (TCSCD): This type of device is controlled by tension loading, where the rod is attached or engaged by the device and allows the rod to ratchet through as the wood shrinks. The Simpson Strong-Tie Ratcheting Take-Up Device (RTUD) is of this type.

- Tension-controlled Shrinkage Compensating Coupling Device (TCSCCD): This type of device is controlled by tension loading that connects rods or anchors together. The Simpson Strong-Tie Coupling Take-Up Device (CTUD) is of this type.

Each device type has unique features that are important in achieving the best performance for different conditions and loads. The following table is a summary of each device.

The most cost-effective Simpson Strong-Tie shrinkage compensation device is the RTUD. This device has the smallest number of components and allows the rod unlimited travel through the device. It is ideal at the top level of a rod system run or where small rod diameters are used. Simpson Strong-Tie RTUDs can now accommodate 5/8″ (RTUD5) and ¾” (RTUD6) diameter rods.

The most cost-effective Simpson Strong-Tie shrinkage compensation device is the RTUD. This device has the smallest number of components and allows the rod unlimited travel through the device. It is ideal at the top level of a rod system run or where small rod diameters are used. Simpson Strong-Tie RTUDs can now accommodate 5/8″ (RTUD5) and ¾” (RTUD6) diameter rods.

How do you choose the best device for your projects? A Designer will have to consider the following during their design.

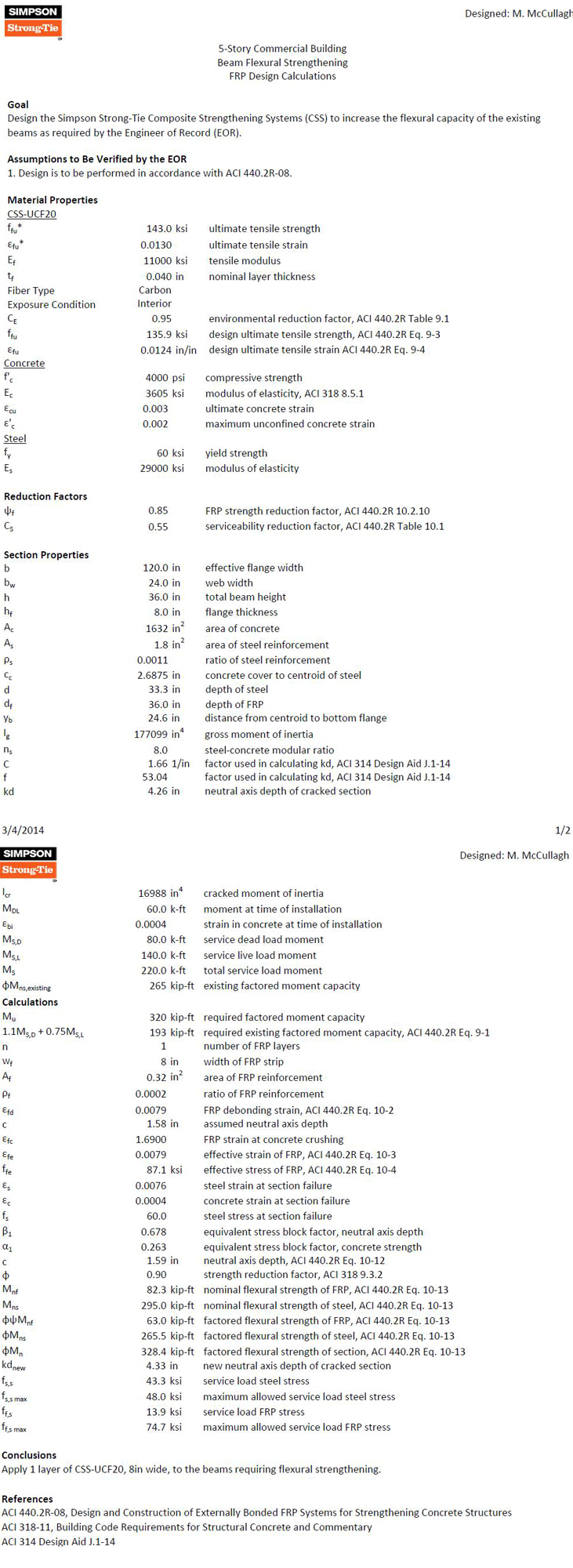

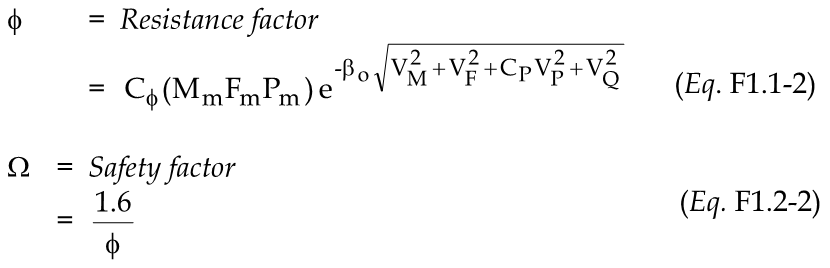

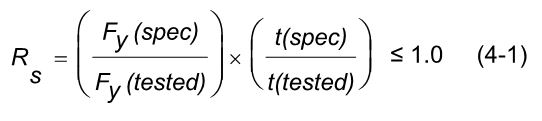

Rod Tension (Overturning) Check:

- Rods at each level designed to meet the cumulative overturning tension force per level

- Standard and high-strength steel rods designed not to exceed tensile capacity as defined in AISC specification

- Standard threaded rod based on 36 / 58 ksi (Fy/Fu)

- High-strength Strong-Rod based on 92 / 120 ksi (Fy/Fu

- H150 Strong-Rod based on 130 / 150 ksi (Fy/Fu)

- Rod elongation (see below)

Bearing Plate Check

- Bearing plates designed to transfer incremental overturning force per level into the rod

- Bearing stress on wood member limited in accordance with the NDS to provide proper bearing capacity and limit wood crushing

- Bearing plate thickness has been sized to limit plate bending in order to provide full bearing on wood member

Shrinkage Take-Up Device Check

- Shrinkage take-up device is selected to accommodate estimated wood shrinkage to eliminate gaps in the system load path

- Load capacity of the take-up device compared with incremental overturning force to ensure that load is transferred into rod

- Shrinkage compensation device deflection is included in system displacement

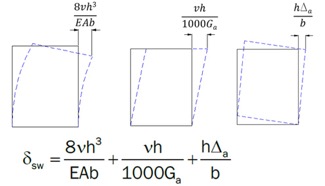

Movement/Deflection Check

- System deformation is an integral design component impacting the selection of rods, bearing plates and shrinkage take-up devices

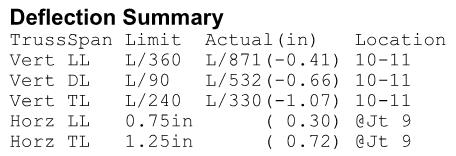

- Rod elongation plus take-up device displacement is limited to a maximum of 0.2″ per level or as further limited by the requirements of the engineer or jurisdiction

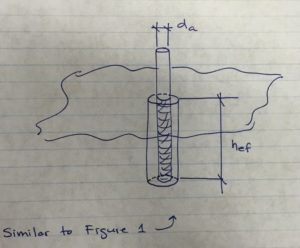

- Total system deformation reported for use in Δa term (total vertical elongation of wall anchorage system per NDS equation) when calculating shearwall deflection

- Both seating increment (ΔR) and deflection at allowable load (ΔA) are included in the overall system movement. These are listed in the evaluation report ICC-ES ESR-2320 for take-up devices

Optional Compression Post Design

- Compression post design can be performed upon request along with the Strong-Rod System

- Compression post design limited to buckling or bearing perpendicular to grain on wood plate

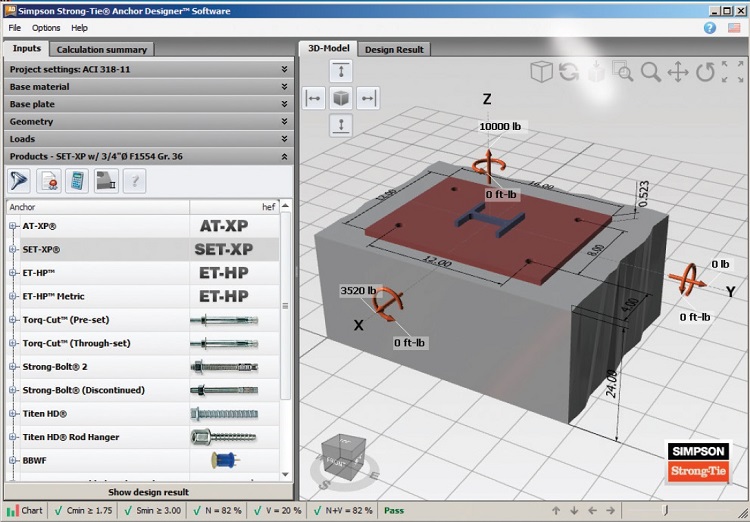

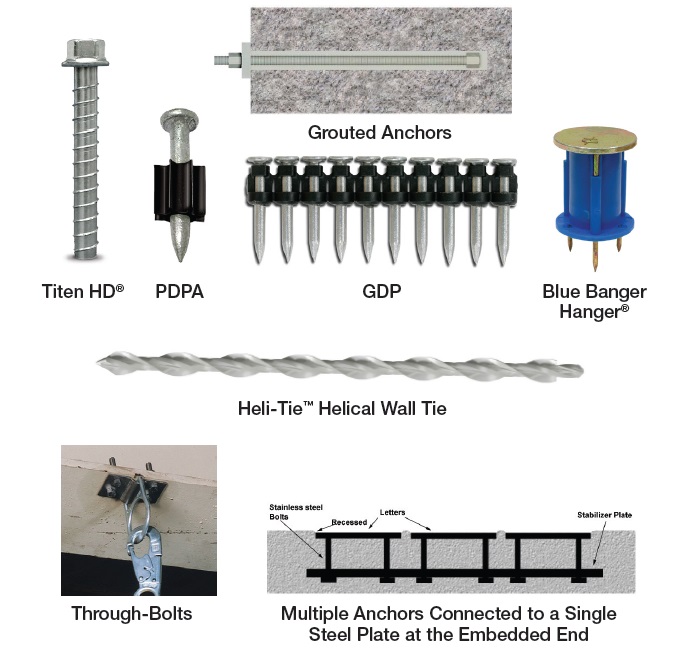

- Anchorage design tools are available

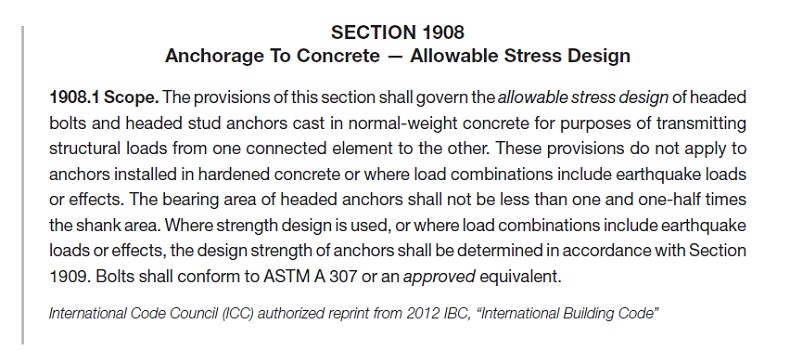

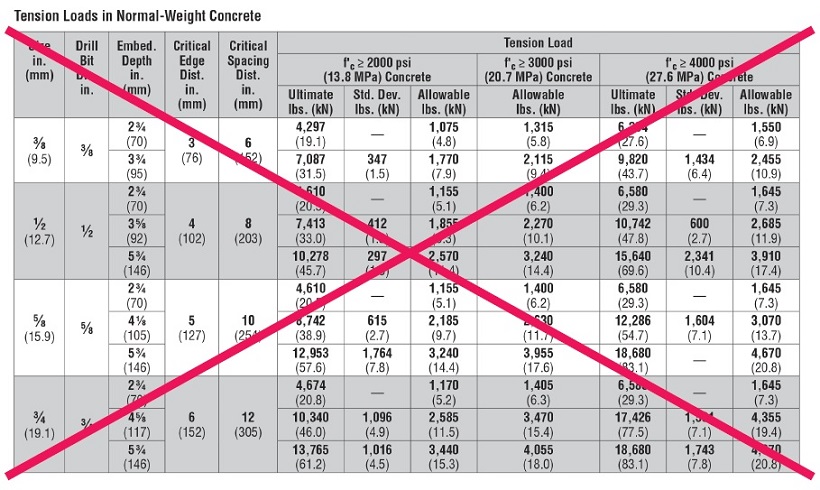

- Anchorage design information conforms to AC 318 anchorage provisions and Simpson Strong-Tie testing

In order to properly design a continuous rod tie-down system for your shearwall overturning restraint, all of the factors listed above will need to be taken into consideration.

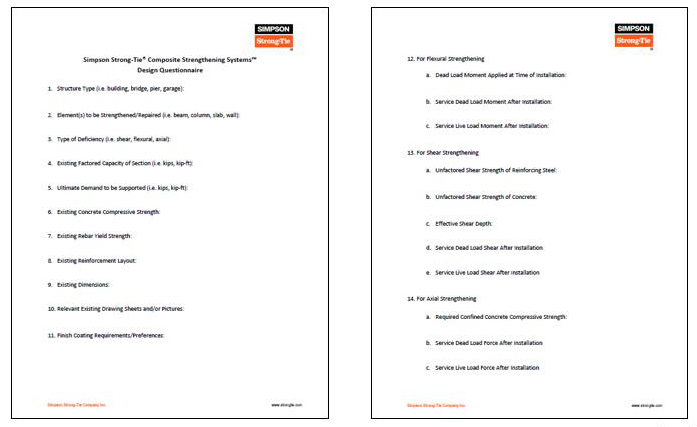

A Designer can also contact Simpson Strong-Tie by going to www.strongtie.com/srs and filling out the online “Contact Us” page to have Simpson Strong-Tie design the continuous rod tie-down system for you. This design service does not cost you a dime. A few items will be required from the Designer in order for Simpson Strong-Tie to create a cost-effective rod run (it is recommended that on the Designer specify these in the construction documents):

- There is a maximum system displacement of 0.2″ per level, which includes rod elongation and shrinkage compensation device deflection. Some jurisdictions may impose a smaller deflection limit.

- Bearing plates and shrinkage compensation devices are required at every level.

- Cumulative and incremental forces must be listed at each level in Allowable Stress Design (ASD) force levels.

- Construction documents must include drawings and calculations proving that design requirements have been met. These drawings and calculations should be submitted to the Designer for review and the Authority Having Jurisdiction for approval.

More information can be obtained from our website at www.strongtie.com/srs, where a new design guide for the U.S., F-L-SRS15, and a new catalog for Canada, C-L-SRSCAN16, are available for download.