This blog post continues our series on the final results of the 2016 ICC Group B Code Change Hearings. This post will focus on approved changes to the International Residential Code (IRC) that are of a structural nature. The changes outlined here will be contained in the 2018 IRC, which is expected to be published in the fall of this year.

In Chapter 3, the seismic design category / short-period design spectral response acceleration maps will be updated to match the new USGS/NEHRP Seismic Maps. These new maps are based on the worst case assumption for Site Class. Significantly, a new set of maps will be provided in Figure 301.2(3) “Alternate Seismic Design Categories”. These are permitted to be used when the “soil conditions are determined by the building official to be Site Class A, B or D.” See page 29 of the linked document for the new maps and a good explanation of the changes that will be occurring in various parts of the country. In addition, the ICC Building Code Action Committee authored a reorganization of the seismic provisions of Chapter 3 to try to reduce confusion.

Another change in Chapter 3 will clarify that guards are only required on those portions of walking surfaces that are located more than 30 inches above grade, not along the entire surface. To bring consistency with the IBC, another change will require that staples in treated wood be made of stainless steel.

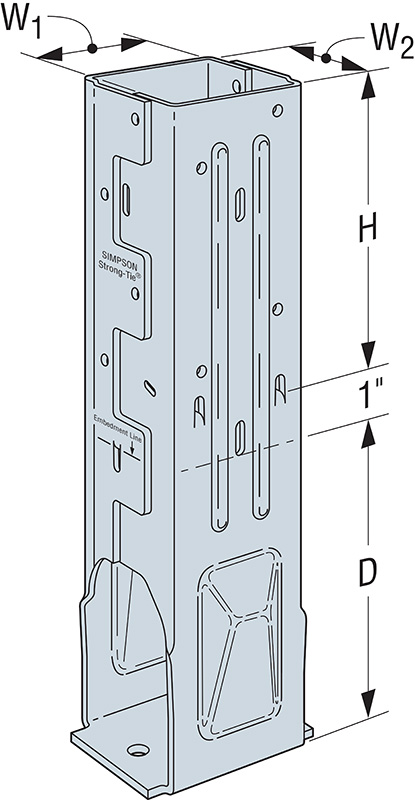

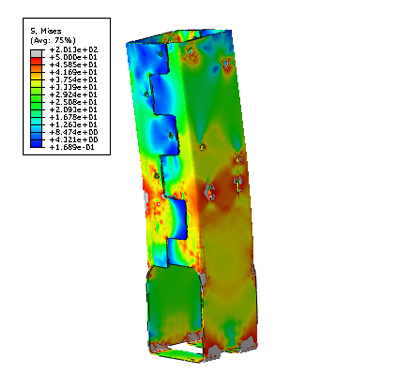

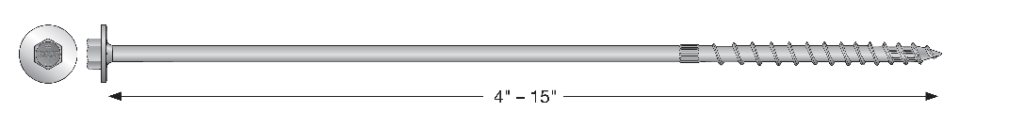

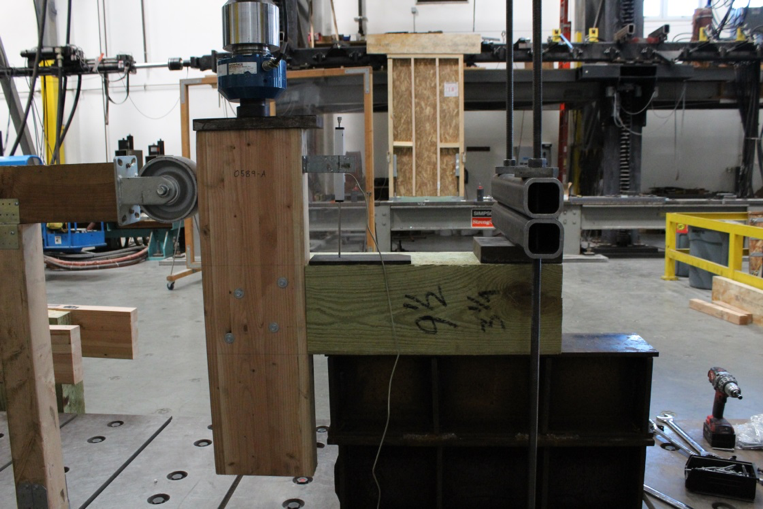

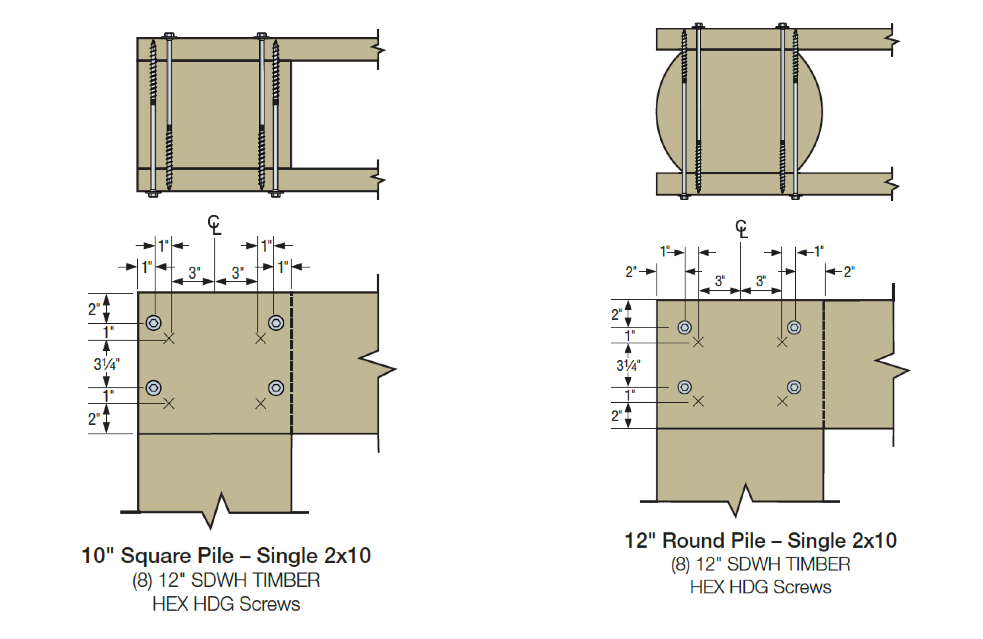

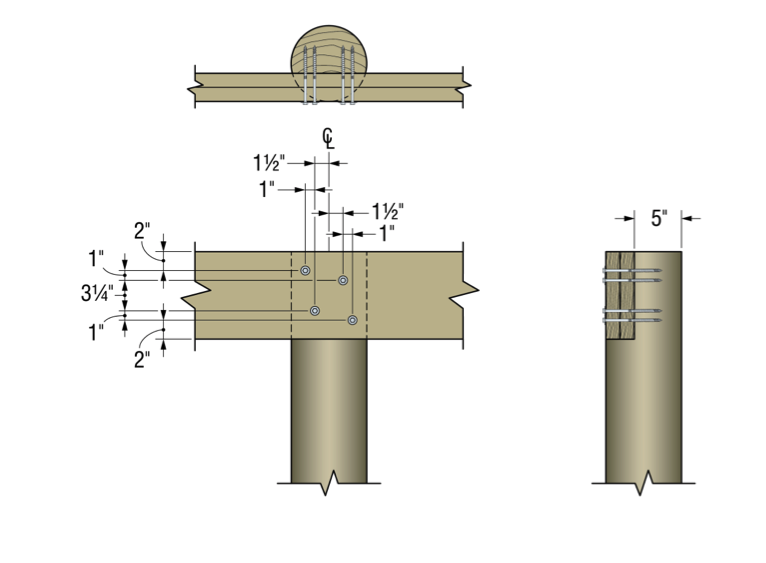

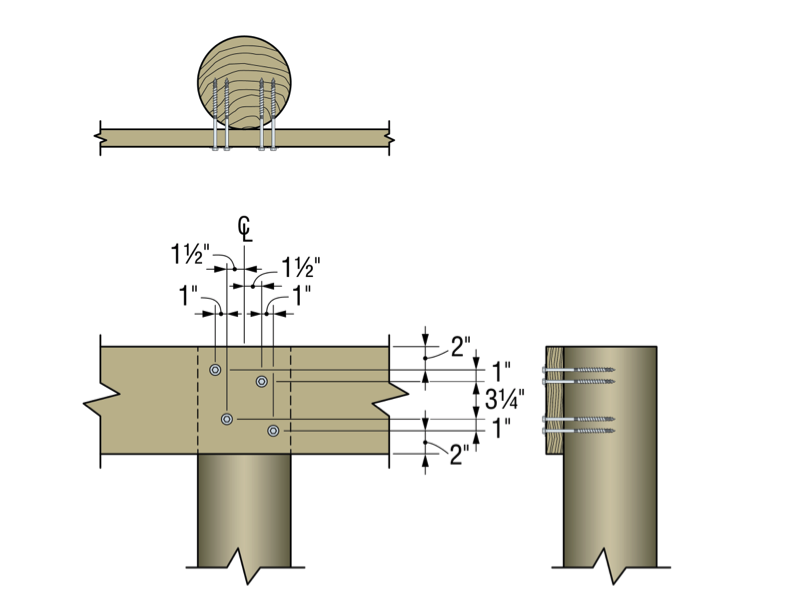

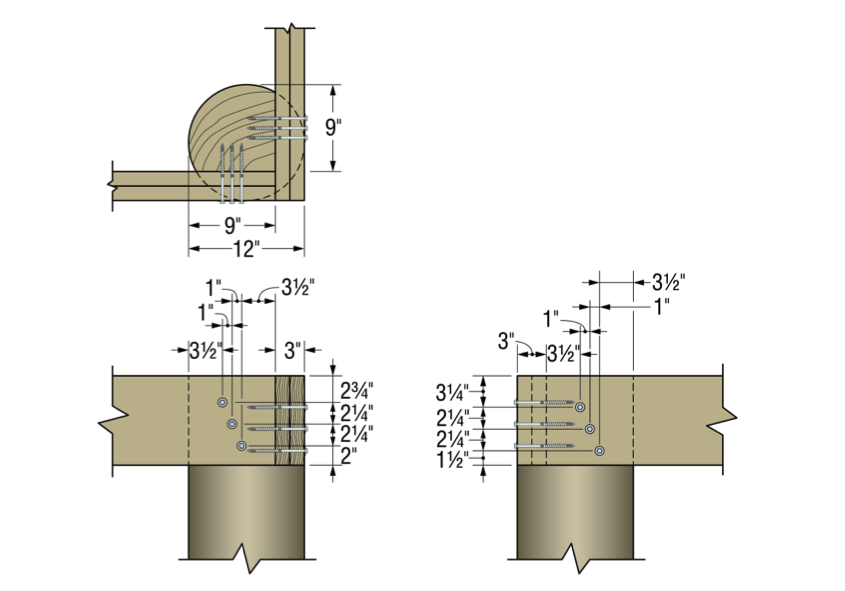

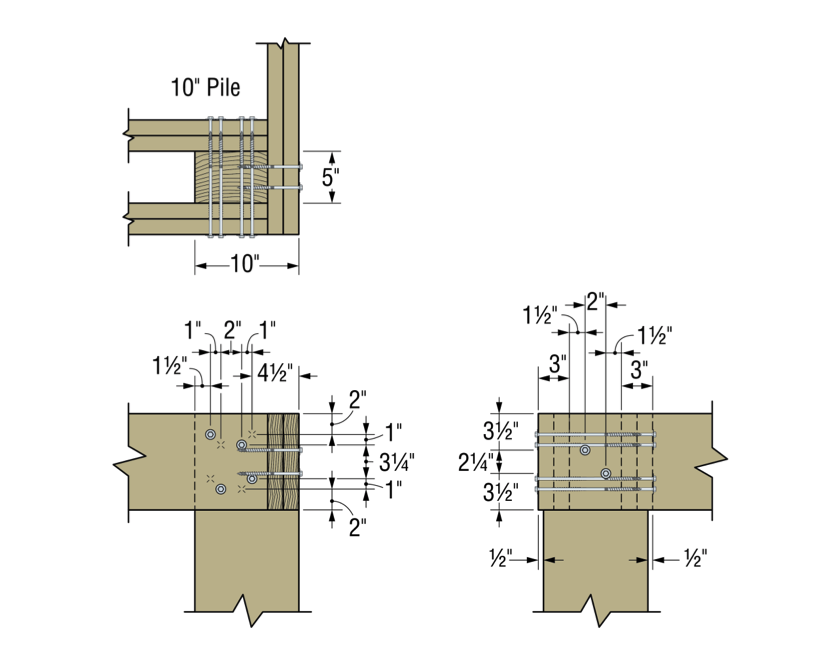

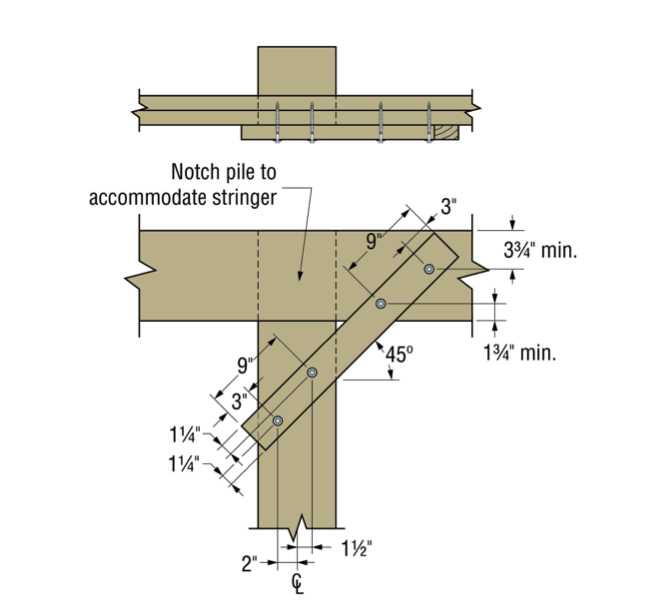

A broad group of parties interested in deck safety, known as the Deck Code Coalition, submitted 17 different code changes with revisions to Section R507 on decks. Of those, 12 were approved, making significant changes to that section. The various approved changes included the following: a complete re-write of that section; new/clarified requirements for deck materials, including wood, fasteners and connectors; clarified requirements for vertical and lateral connections of the deck to the supporting structure; new requirements for sizes of deck footings and specification that deck footings must extend below the frost line, with certain exceptions; clarification for deck board material, including an allowance for alternative decking materials and fastening methods; adding new columns to the deck joist span table that show the maximum cantilever for joists; adding the allowance for 8×8 deck posts, to allow notching for the support of a three-ply beam; and clarification of the deck-post-to-footing connection.

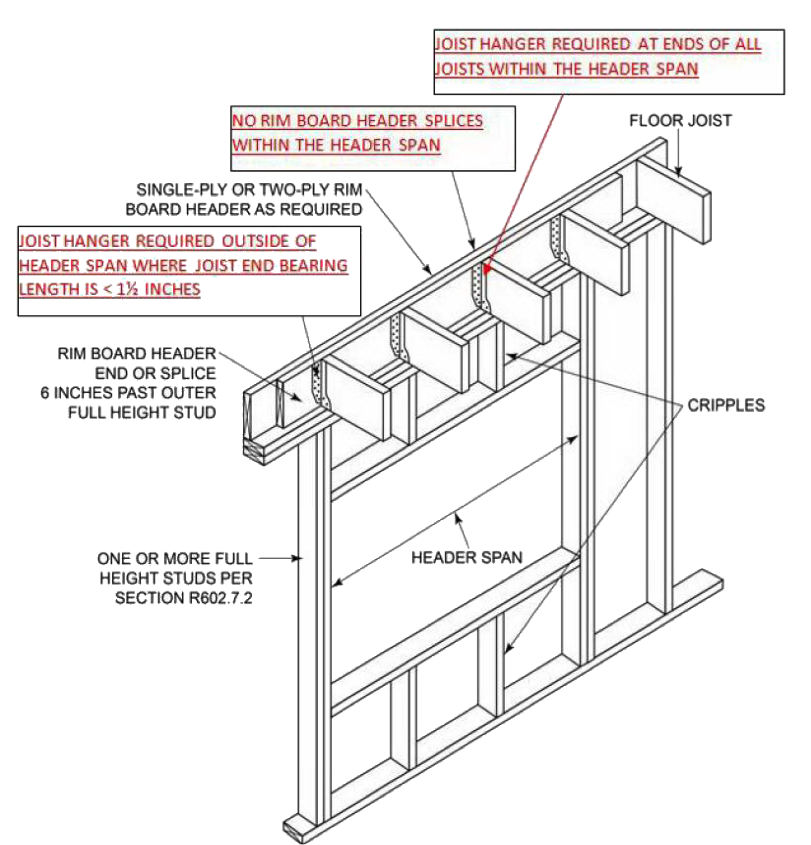

In Chapter 6, a new table permitting 11ʹ- and 12ʹ- long studs was added. In the 2015 IRC, load-bearing studs were limited to 10 feet in length. A new high-capacity nail, the RSRS (Roof Sheathing Ring Shank) nail was added as an option for fastening roof sheathing. This nail will become more widely used once the higher roof component and cladding forces from ASCE 7-16 are adopted. The rim board header detail that was added for the 2015 IRC was corrected to show that hangers are required in all cases when the joists occur over the wall opening.

There were several changes made to the Wall Bracing Section, R602.10. The use of the 2.0 increase factor was clarified for use when the horizontal joints in braced wall panel sheathing are not blocked. Narrow methods were added to the column headings for the wind and seismic bracing amount tables, to make them consistent, and the methods for adding different bracing were clarified. When using bracing method PFH, the builder can omit the nailing of the sheathing to the framing behind the strap-type holdown. Finally, offering some relief for high-seismic areas where brick veneer is used, an allowance was added to permit a limited amount of brick veneer to be present on the second floor without triggering the use of the BV-WSP bracing method.

There were several changes made to the Wall Bracing Section, R602.10. The use of the 2.0 increase factor was clarified for use when the horizontal joints in braced wall panel sheathing are not blocked. Narrow methods were added to the column headings for the wind and seismic bracing amount tables, to make them consistent, and the methods for adding different bracing were clarified. When using bracing method PFH, the builder can omit the nailing of the sheathing to the framing behind the strap-type holdown. Finally, offering some relief for high-seismic areas where brick veneer is used, an allowance was added to permit a limited amount of brick veneer to be present on the second floor without triggering the use of the BV-WSP bracing method.

In Chapter 8, the requirements for a “stick-framed” roof system were completely re-written to make such systems easier to use.

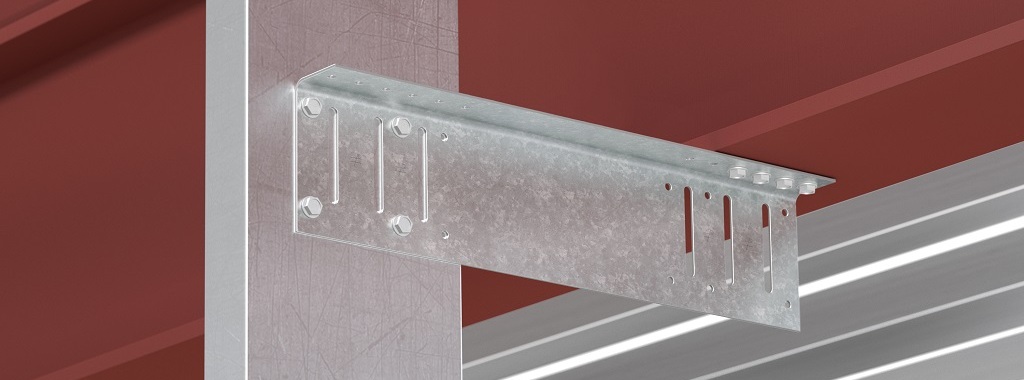

A couple of significant changes were made to the prescriptive requirements for cold-formed steel framing. The requirements for the anchorage of cold-formed steel walls were revised, and the wind requirements for cold-formed steel framing were changed to match the new AISI S230 prescriptive standard.

Finally, it may be helpful to mention some of the proposed changes that were not adopted. While the new ASCE 7-16 was adopted as the IRC reference standard for loads as part of the Administrative changes, several changes to the IRC to make it consistent with ASCE 7-16 were not approved. A change to update the IRC wind speed maps, roof component and cladding pressures, component and cladding roof zones, and revise the remainder of wind-based requirements to match ASCE 7-16 was not approved. Similarly, a proposal to increase the live load on decks, from 1.0 to 1.5 times the occupancy served, was denied.

Once the IRC is published, it will be time to start a new code change cycle once again, with Group A code changes due January 8, 2018. The schedule for the next cycle is already posted here.

What changes would you like to see for the 2021 codes?