Designing built-up columns? Now there’s a way to mechanically laminate multiple 2x members to meet the specifications in the National Design Specifications for wood. Simpson Strong-Tie evaluated Strong-Drive® SDW Truss-Ply screws for attaching multiple laminations with easier installation methods. With these screws, there’s no longer a need to nail from both sides of the column, or to use not-so-common 30d nails as specified in the NDS, or to pre-drill for bolts. Instead, installers can now install all the screws from one side of the built-up column, which provides time and cost savings.

Category: Testing/R&D

Simpson Strong-Tie is constantly testing and innovating.

Wood-framed Deck Guard Post Resources and Residential Details

A deck and porch study reported that 33% of deck failure-related injuries over the 5-year study period were attributed to guard or railing failures. While the importance of a deck guard is widely known, there was a significant omission from my May 2014 post on Wood-framed Deck Design Resources for Engineers regarding the design of deck guards.

A good starting point for information about wood-framed guard posts is a two-part article published in the October 2014 and January 2015 issues of Civil + Structural Engineer magazine. “Building Strong Guards, Part 1” provides an overview of typical wood-framed decks, the related code requirements and several examples that aim to demonstrate code-compliance through an analysis approach. The article discusses the difficulties in making an adequate connection at the bottom of a guard post, which involve countering the moment generated by the live load being applied at the top of the post. Other connections in a typical guard are not as difficult to design through analysis. This is due to common component geometries resulting in the rails and balusters/in-fill being simple-supported rather than cantilevered. “Building Strong Guards, Part 2” provides information on the testing approach to demonstrate code-compliance. Information about code requirements and testing criteria are included in the article as well.

Research and commentary from Virginia Tech on the performance of several tested guard post details for residential applications (36” guard height above decking) is featured in an article titled “Tested Guardrail Post Connections for Residential Decks” in the July 2007 issue of Structure magazine. Research showed that the common construction practice of attaching a 4×4 guard post to a 2x band joist with either ½” diameter lag screws or bolts, fell significantly below the 500 pound horizontal load target due to inadequate load transfer from the band joist into the surrounding deck floor framing. Ultimately, the research found that anchoring the post with a holdown installed horizontally provided enough leverage to meet the target load. The article also discussed the importance of testing to 500 pounds (which provides a safety factor of 2.5 over the 200-pound code live load), and the testing with a horizontal outward load to represent the worst-case safety scenario of a person falling away from the deck surface.

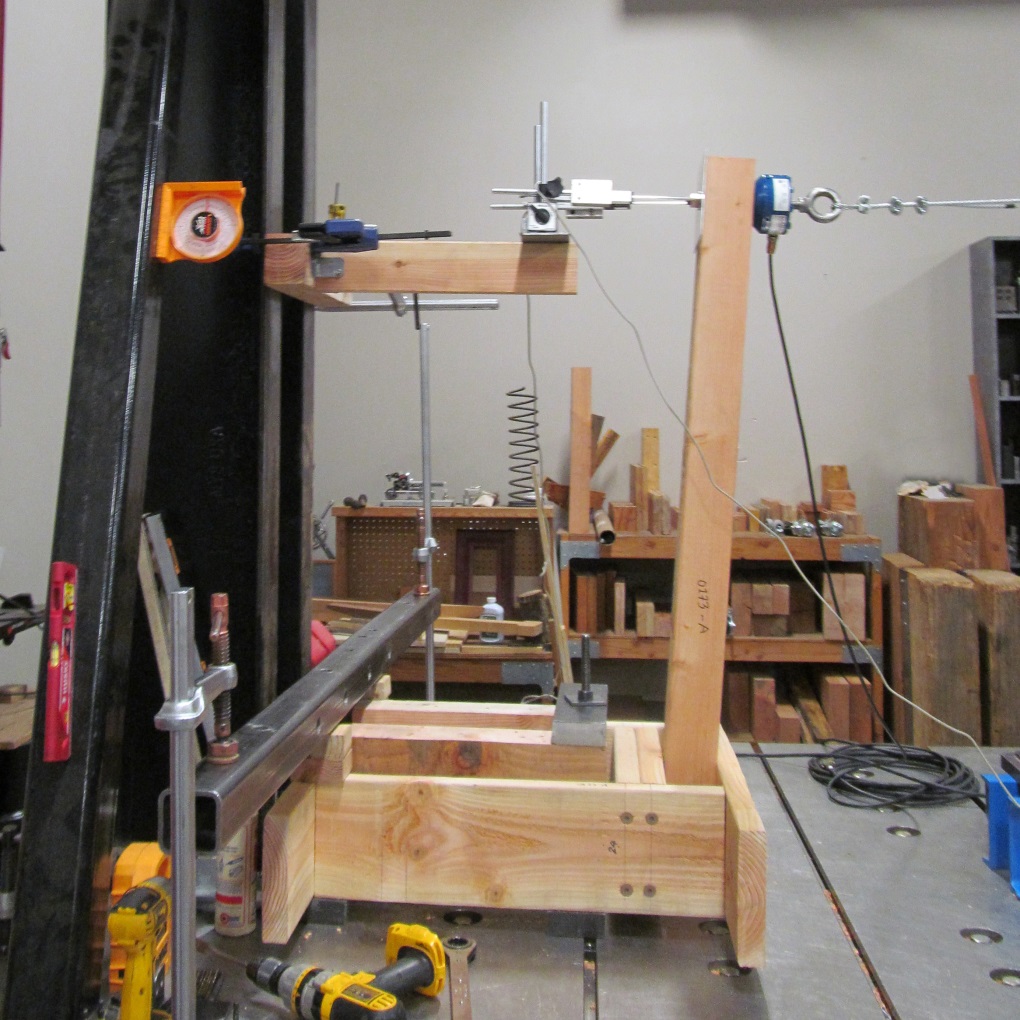

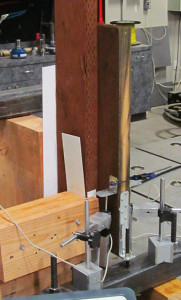

Simpson Strong-Tie has tested several connection options for a guard post at the typical 36” height, subjected to a horizontal outward load. Holdown solutions are included in our T-GRDRLPST10 technical bulletin. In response to recent industry interest, guard post details utilizing blocking and Strong-Drive® SDWS TIMBER screws have been developed (see picture below for a test view) and recently released in the engineering letter L-F-SDWSGRD15. The number of screws and the blocking shown are a reflection of the issue previously identified by the Virginia Tech researchers – an adequate load path must be provided to have sufficient support.

Have you found any other resources that have been helpful in your guard post designs? Let us know by posting a comment.

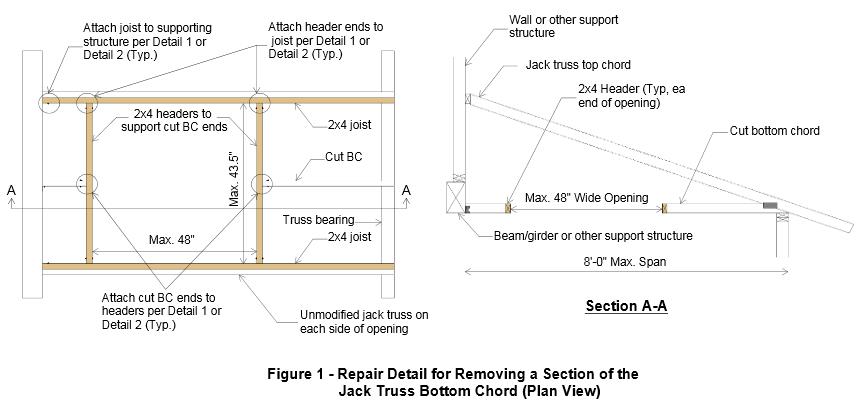

Truss Repair Information: The Never-Ending Search

Truss repair is one of the most frequently asked about truss topics. Not surprisingly, when we asked for suggested truss topics in a truss blog earlier this year, truss repair information made the list. Because the summer months bring about a peak in new construction – and plenty of truss repairs to go along with it – the beginning of June is the perfect time to visit this topic.

From trusses that get dropped or cut/drilled/notched at the jobsite, to homeowners who want to modify their existing trusses to add a skylight or create attic space to fire-damaged trusses, a multitude of scenarios fall under the broad topic of truss repair. Today’s post focuses on various references and resources that can provide some assistance. But first it helps to break down the broad “truss repair” topic into more manageable-sized categories.

New Construction vs. Recent Construction vs. Old Construction

By far, the easiest type of truss repair is new construction, when the trusses either haven’t been installed yet or are still in the process of being installed. Whether the repair is relatively simple (e.g. a broken web) or a little more complicated (e.g. the trusses need to be stubbed), the beauty of new truss construction is that the truss manufacturer – and truss Designer – can be contacted and help with the repair. The truss Designer can easily open up the truss designs in the truss design software, quickly evaluate the trusses for the appropriate field conditions and issue a repair.

A good reference related to truss repairs for new truss construction is the Building Component Safety Information (BCSI) booklet jointly produced by SBCA and TPI. Section B5 of the BCSI booklet, which is also available as a stand-alone summary sheet, covers Truss Damage, Jobsite Modifications & Installation Errors. This field-guide document describes the steps to take when a truss at the jobsite is damaged, altered or improperly installed, common repair techniques, and the information to provide to the truss manufacturer when a truss is damaged, which will assist in the repair process.

The next easiest truss type to repair is recent construction, where the trusses were constructed recently enough that: a) the truss plates are easy to identify, and b) the truss design drawings may even still be available. In these cases, design professionals other than the original truss Designer may be contacted to repair the trusses. For some types of repairs, the design professional can work off the truss design drawing to design the repair. Other times it might be necessary to model and analyze the truss using structural design software; alternatively, a truss manufacturer can be contacted to model the truss in their truss design software for a fee.

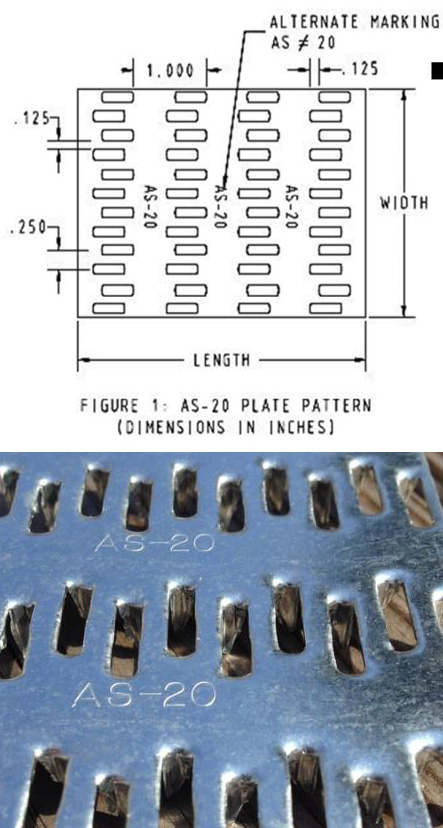

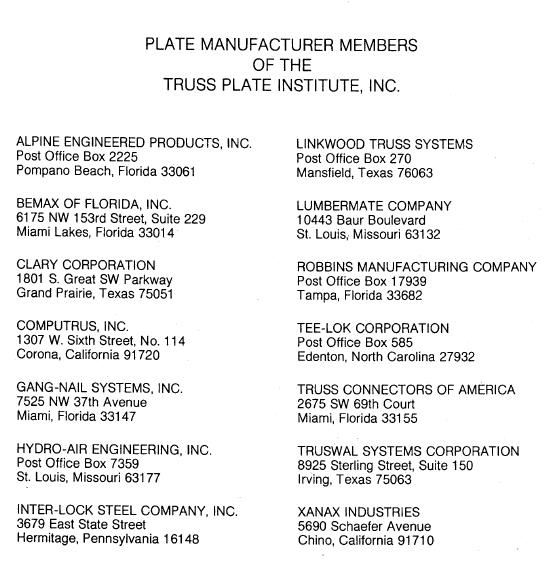

Often, the design professional wants to know the design values for the truss plates that were used to construct the truss. If there are truss design drawings available, they will indicate which truss plates were used in the design, and then the truss plate manufacturer can be contacted for more information. It is also easy to search for the truss plate code reports online (for instance, check icc-es.org). If no truss design drawing is available, there is still a way to identify the truss plates. Currently, there are only five major truss plate manufacturers in the United States, and they are listed on the Truss Plate Institute website. That makes identification of the truss plates used in recently constructed trusses easier because all of the current manufacturers’ plates will have markings that are described in their code reports. (Note that there are also a couple of truss manufacturers in the U.S. that manufacture their own truss plates.)

Finally, the most challenging type of trusses for truss repairs are those found in older buildings. Design professionals involved in these types of repair often aren’t sure where to start. Truss design drawings are often not available, and the act of trying to identify the truss plate manufacturer is challenging at best, unsuccessful at worst. As a point of reference, there were 14 truss plate manufacturers that were TPI members in 1987 (see image below), and only one of those companies is still in the current list of five companies. Therefore, the truss plates found in a truss built around 1987 will be difficult to identify. One option is to contact TPI and see if they can point you in the right direction.

Simple vs. Complex Repairs

Another way to break down truss repairs is to divide them into easy and challenging repairs. People often ask for “standard” truss repair details. Unfortunately, standard details only address the simplest types of repair; and those usually aren’t the types of repair that are asked about. Details simply cannot cover the wide range of truss configurations and every type of repair situation.

With the exception of simple repairs, most truss repairs rely heavily on the judgment and experience of the design professional doing the repair. And because there are not entire textbooks devoted to truss repair (that I am aware of, anyway), Designers must pull from a variety of resources, both to learn more about truss repair and to design the repair. For repairs using plywood or OSB gussets, the APA Panel Design Specification is a must-have reference. Some people prefer to use dimension lumber scabs for their repairs, whenever possible, simply because they are more familiar with dimension lumber (and the NDS) than they are with Plywood/OSB or the APA Panel Design Specification.

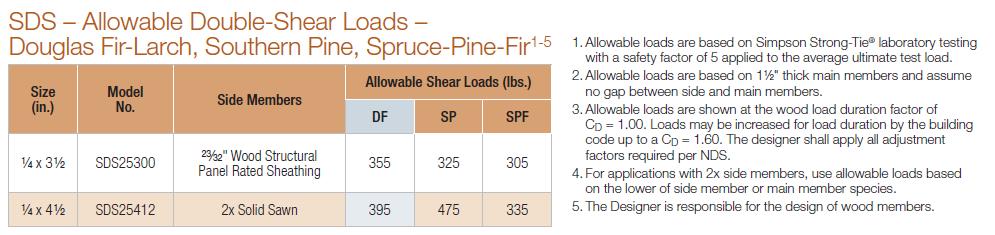

Next, the fasteners for the repair must be selected and the allowable loads determined. For nail design values, I am a big fan of the American Wood Council’s Connection Calculator, which provides allowable nail shear values for just about any combination of main and side members that you can think of, including OSB and plywood side members – particularly handy for truss repairs. For more complex repairs, and especially repairs involving higher forces, an excellent fastener choice is a structural wood screw such as our Strong-Drive® SDS or SDW screws. When I worked in the R&D department at Simpson Strong-Tie, a frequently asked question was whether we had double-shear values for our SDS screws. The questions always seemed to come from Designers who wanted them for truss repairs. Fortunately, we do have double-shear values for our SDS screws.. You can find them on page 319 of our Fastening catalog.

The Strong-Drive SDW screw was developed after the SDS screw, and while there are currently no double-shear values for the SDW, it is still another good option for repairs.

Fire-Damaged Trusses and Truss Collapses

These situations are in a category by themselves because they go beyond even the most complex repairs involving a major modification to the truss. The biggest difference is that the latter case involves mostly known facts and perhaps some conservative assumptions, whereas damage due to fire or collapse includes many unknowns. Most of the truss Designers I have spoken to about truss damage due to fire or truss collapse often recommend replacement of the trusses rather than repair because it is usually too difficult to quantify the damage to the lumber and/or joints. In fires, there can be “hidden” damage due to the sustained high temperatures, while the truss appears to have no visible damage. Likewise, in a truss collapse, not only may there be too many breaks in the trusses involved in the collapse, but there may also be trusses that suffered severe stresses during the collapse and have damage that is not visible. To attempt a repair in either of these cases often requires an inspection at the jobsite, and the result may still end up being replacement of some or all of the trusses. Therefore, the cost of a full-blown inspection should be weighed against the cost of replacing the trusses.

The Structural Building Components Association website has a page with information pertaining to fire issues. It includes a couple of documents related to fire damage that are worth checking out.

Beyond the Blog: Where to Get More Truss Repair Information

The best bet for getting practical design information related to truss repairs is to keep an eye out for short courses, workshops or seminars. ASCE has hosted a Truss Repair Seminar (Evaluating Damage and Repairing Metal Plate Connected Wood Trusses) in the past and may very well offer something like it again. Virginia Tech recently hosted a short course on Advanced Design Topics in Wood Construction Engineering, which included a section on Wood Truss Repair Design Techniques.

What other references or resources for truss repair do you use? Are there any upcoming truss repair courses that you know of? Please let us know in the comments below!

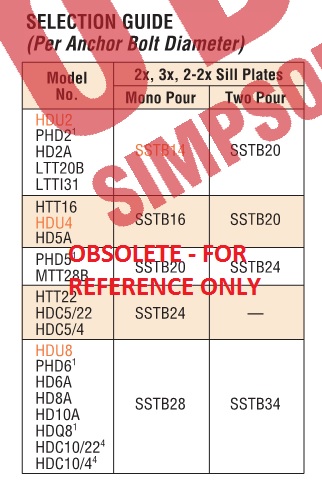

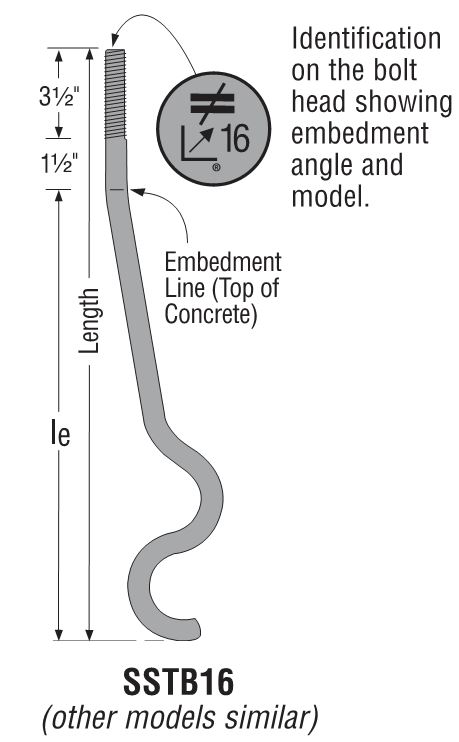

Holdown Anchorage Solutions

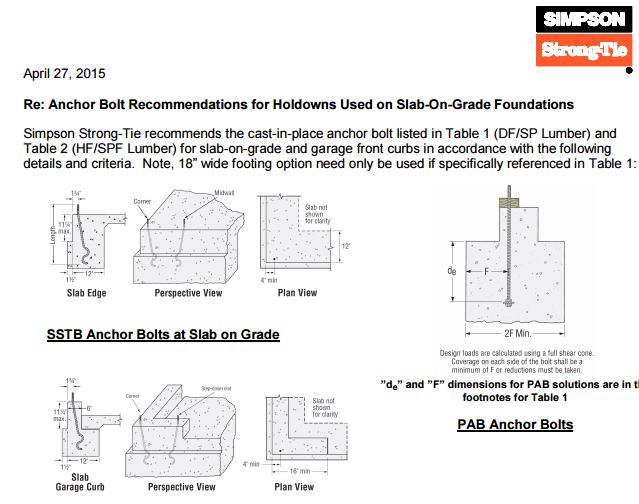

A common question we get from specifiers is “What anchor do I use with each holdown?” Prior to the adoption of ACI 318 Appendix D, this was somewhat simple to do. We had a very small table near the holdown section of our catalog that listed which SSTB anchor worked with each holdown.

During the good old days, anchor bolts had one capacity and concrete wasn’t cracked. ACI 318 Appendix D gives us reduced capacities in many situations, different design loads for seismic or wind and reductions for cracked concrete. These changes have combined to make anchor bolt design more challenging than it was under the 1997 Uniform Building Code.

This blog has had several posts related to holdowns. So, What’s Behind a Structural Connector’s Allowable Load? (Holdown Edition) explained how holdowns are tested and load rated in accordance with ICC-ES Acceptance Criteria. Damon Ho did a post, Use of Holdowns During Shearwall Assembly, which discussed the performance differences of shearwalls with and without holdowns, and Shane Vilasineekul did a Wood Shearwall Design Example. So I won’t get in to how to pick a holdown.

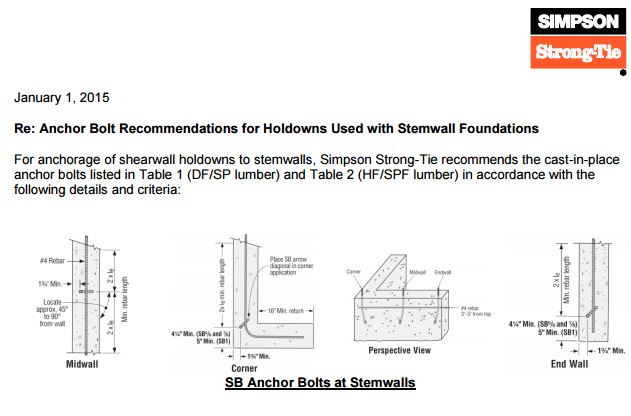

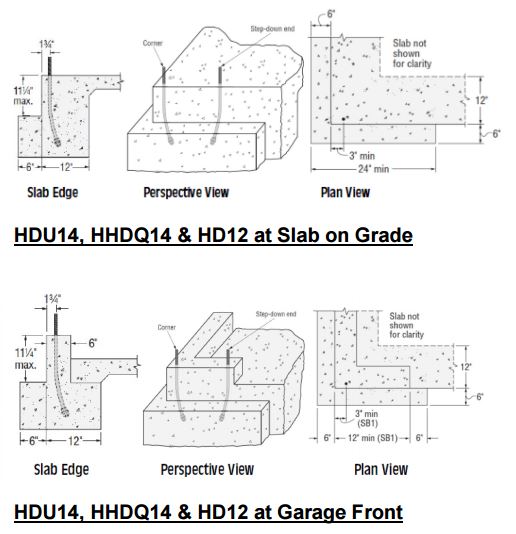

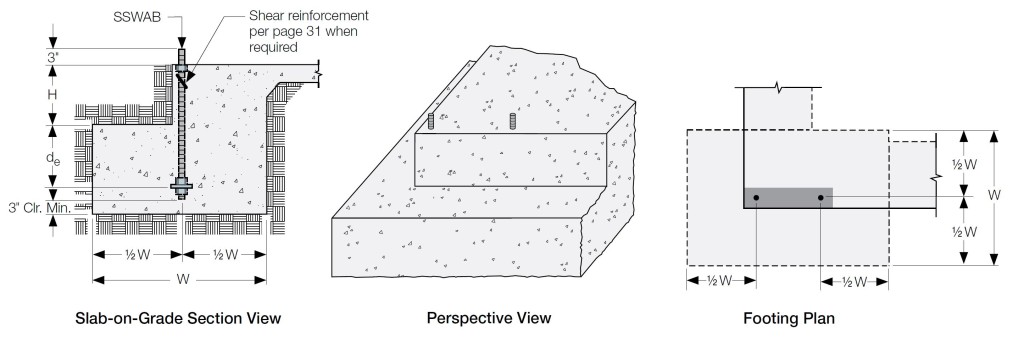

Once you have determined your uplift requirements and selected a post size and holdown, it is necessary to provide an anchor to the foundation. To help Designers select an anchor that works for a given holdown, we have created different tables that provide anchorage solutions for Simpson Strong-Tie holdowns.

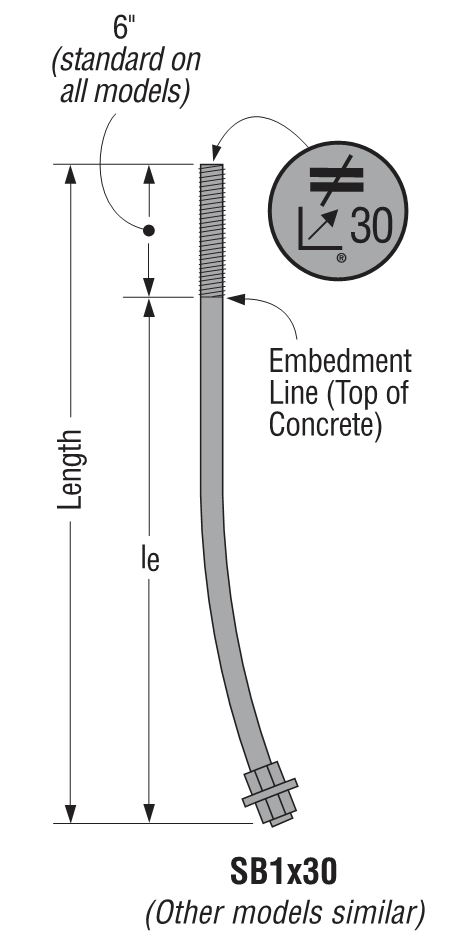

There is one Engineering letter that addresses slab-on-grade foundations and another version that covers stemwall foundations. The tables are separated by wood species (DF/SP and SPF/HF) to give the most economical anchor design for each post material. The preferred anchor solutions are SSTB or SB anchors, as these proprietary anchor bolts are tested and will require the least amount of concrete. When SSTB or SB anchors do not have adequate capacity, we have tabulated solutions for the PAB anchors, which are pre-assembled anchors that are calculated in accordance with ACI 318 Appendix D.

The solutions in the letters are designed to match the capacity of the holdowns, which allows the contractor to select an anchor bolt if the engineer doesn’t specify one. They are primarily used by engineers who don’t want to design an anchor or select one from our catalog tables. We received some feedback from customers who were frustrated that some of our heavier holdowns required such a large footing for the PAB anchors, whereas a slightly smaller holdown worked with an SB or SSTB anchor in a standard 12″ footing with a 1½” pop out.

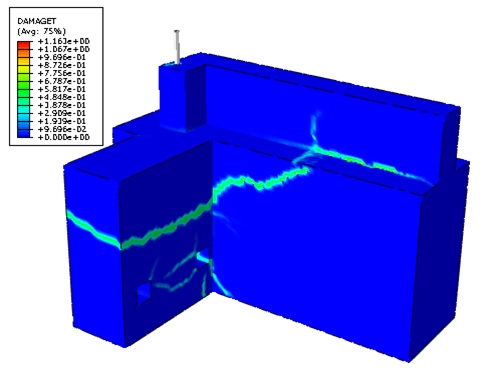

To achieve smaller footings using our SB1x30 anchor bolts, we reviewed our original testing and created finite element (FEA) models to determine what modifications to the slab-on-grade foundation details would meet our target loads. Of course, we ran physical tests to confirm the FEA models. With a 6″ pop out, we were able to achieve design loads for HD12, HDU14 and HHDQ14.

The revised footing solutions for the heavier holdowns require less excavation and less concrete than the previous Appendix D calculated solutions, reducing costs on the installation.

What has been your experience with holdown anchorage? Tell us in the comments below.

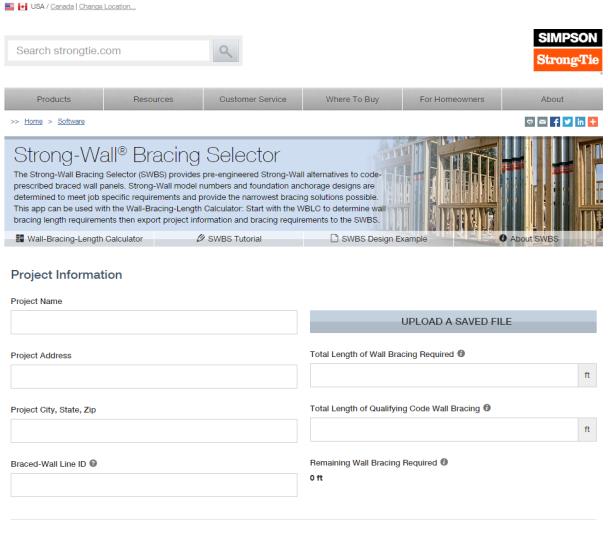

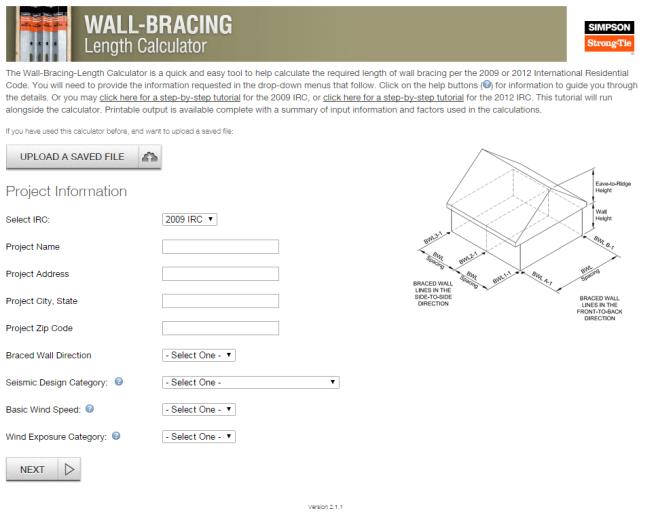

Strong-Wall Bracing Selector: Bridging the Gap between Engineered Design and Prescriptive Construction

Asking a structural engineer to design wall bracing under the IRC® can be like asking a French pastry chef to bake a cake using Betty Crocker’s Cookbook. The temptation is to toss out the prescriptive IRC recipe and design the house using ASCE 7 loads and the AWC SDPWS shear wall provisions per the IBC®. But if only a portion of the house needs to be engineered, there may be an easier option.

The prescriptive IRC states an IBC engineered design “is permitted for all buildings and structures and parts thereof” but the design must be “compatible with the performance of the conventional framed system.” But how exactly does an IRC braced wall panel perform? The code doesn’t come right out and tell us, but there are two bracing methods that are essentially shear walls masquerading as braced wall panels: Method ABW and Method BV-WSP. Backing into their allowable loads gives us the key to determining equivalence and eliminates the need to develop lateral forces.

But before you can bust out the slide rule and start crunching numbers, you need to figure out how much bracing the prescriptive code requires. We developed our Wall-Bracing-Length Calculator in 2010 to help designers do just that. And last month, we launched our Strong-Wall® Bracing Selector tool to make it easier to specify equivalent solutions for tricky situations.

You can export the required lengths (and project information) from the Wall-Bracing-Length Calculator directly into the Strong-Wall Bracing Selector or you can manually enter in the required lengths. The selector app will provide a list of Strong-Wall panels that have an equivalent length, evaluate their anchorage loads and return a list of pre-engineered anchor solutions for a variety of foundation types.

If you’re familiar with our Strong-Wall Prescriptive Design Guide (T-SWPDG10), the selector automates this 84-page document in just a few steps. One big upgrade is the ability to select a solution to meet the exact amount of bracing that is required. If you needed 2.8-ft. of wall bracing, you have to round up to the tabulated 4-ft. solutions if you are using the guide, but now you can select a wall solution that is equivalent to 2.8-ft., which might mean a smaller wall width or better anchor options. You also have the ability to save the selector file for later modifications, create a PDF of the job-specific output, or email the PDF directly from the program.

So next time you get asked to “design” some wall bracing, see if our Wall-Bracing-Length Calculator and Strong-Wall Bracing Selector might save you some time. There is a tutorial and a design example on the Bracing Selector web page, but it’s very easy to use so you may just want to dive right in. I should also point out that the Strong-Wall SB panels have not yet been implemented into the program, but bracing information for them is available on strongtie.com in posted letters for wind (L-L-SWSBWBRCE14), seismic (L-L-SWSBSBRCE14), and seismic with masonry veneer (L-L-SWSBVBRCE14).

Let us know what you think of this new tool in the comments below.

Deck Fasteners – Deck Board to Framing Attachments

When you’re building a deck, it’s important to know the types of fasteners you need to use with the various materials that are available. On this week’s post we explore some deck fastener applications as well as offer suggestions on how to avoid a few common problems. We will address two generic types of deck boards fastened to wood framing: preservative-treated wood and composite decking.

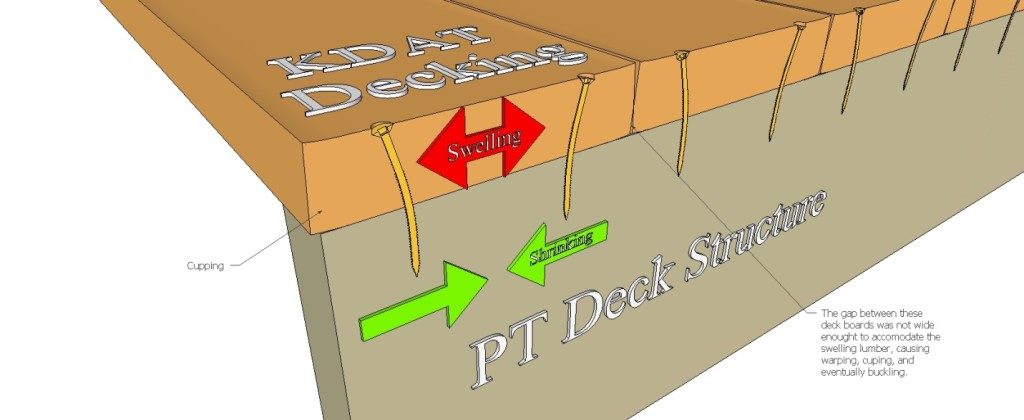

Preservative-Treated Wood Decking

With preservative treated wood, it pays to know the board treatment. Wood is treated with a water-borne treatment chemical (typically micronized copper azole these days) and then it is either sent out wet or it is kiln dried. Wet-treated wood can have a moisture content (MC) greater than 30%. Wood that is subsequently kiln dried to remove excess moisture after the treatment process is labeled Kiln-Dried After Treatment (KDAT) and has a MC of about 15%. Wood deck boards with preservative treatments will be labeled as such regardless of their moisture condition.

The moisture condition of the deck boards determines how best to fasten and space your deck boards. Wet wood will shrink in width and thickness after installation. As a result, you should install these boards butted tight so that gaps will emerge after they dry in place. On the other hand, KDAT wood or wood that is dry should be installed with 1/8” gaps between boards so there is a slight gap after the boards get wet and swell due to rain, ice and snow. Some manufacturers suggest using an 8d common nail for spacing when installing KDAT decking, as seen in the figure below.

Shrinking and swelling of any installed deck board can cause the deck fastener to bend back and forth with the MC cycling. This causes many deck fasteners to break because of the fatigue loading, which can be exacerbated by the brittle steel used in most deck screws.

To combat this problem, Simpson Strong-Tie developed the DSV Wood screw. This screw is specifically designed with increased ductility to handle the bending induced by deck board movement. It is available in a variety of lengths with threads optimized to prevent jacking between the deck board and the framing, ensuring a snug long-lasting connection.

Composite deck boards are made from a mixture of wood fiber and plastic or are entirely “plastic.” Wood plastic composites and plastic materials exhibit thermal expansion, so they expand and contract in thickness, width and length as a function of temperature and solar heating. Consequently, they typically require a special screw designed for composite decking. Screws for this application will often utilize a two-thread design. The lower thread drives the screw into the framing while the upper thread pulls the loosened composite material back into the hole and holds the deck board tight to the joist. Composite screws also have a cap-style head that covers any residual material left around the screw body and leaves a clean finish. Ductility is important to these screws too.

Given the wide variety of composite deck producers, we designed a screw that works well with all of them. The DCU screw works in all types of composite decking fastened to wood framing.

A note about cellular PVC deck boards: the manufacturers’ recommendation of stainless-steel screws restricts the use of many deck board fasteners. Be sure to read and follow the decking material fastener requirements. Simpson Strong-Tie has a broad offering of painted stainless-steel deck screws available to match PVC deck boards. Find the proper match for your board here.

For other deck fastener applications, including decking fastened to steel framing, and information about other deck fasteners available, see our website product page.

Are there other applications that you want to know about that we didn’t share here? Let us know in the comments below. As always, call us in the Engineering Department if you have questions.

Newest Connector to Satisfy Code

“Does Simpson Strong-Tie write the building code?”

If you work at Simpson Strong-Tie, you get asked this question from time to time when you’re in the field. Over the years, I’ve heard it dozens of times, and because the answer is obviously “no,” it makes you wonder why this belief persists with so many people in the industry. Well, here is my theory: We develop and test products for new code provisions faster than it takes states to adopt the newest codes. So a designer, contractor or building official will often hear about a new Simpson Strong-Tie product or tested application that fills a need before their state building code even defines what that need is. Here are some recent examples:

- The FWAZ foundation anchor released in 2007 for a 2006 IRC provision that addresses soil pressure loads on basement walls

- Strong-Drive® SDS screw testing for deck ledgers published in 2008 as alternates to bolts and lags that weren’t prescribed in the IRC until the 2009 edition

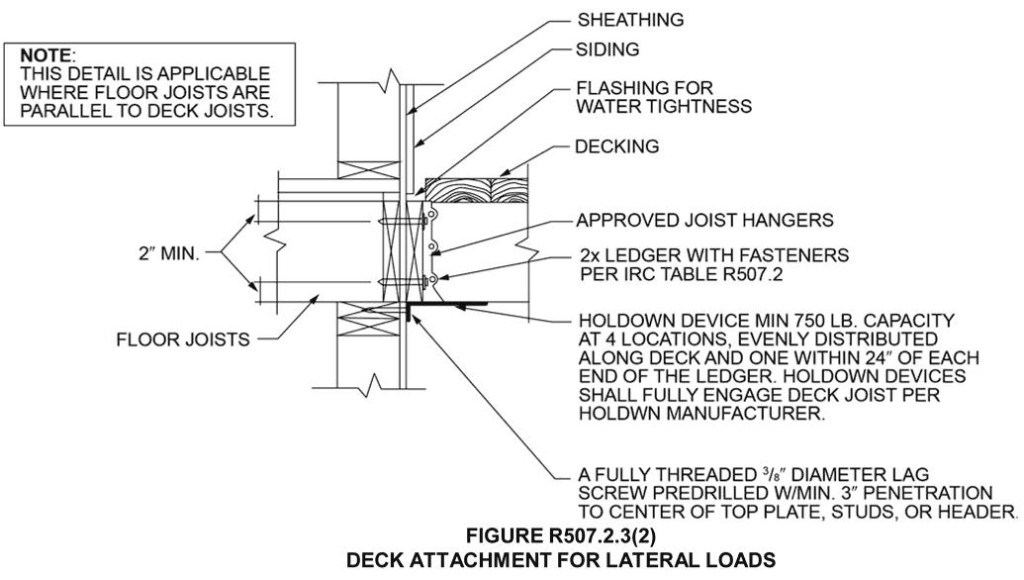

- The DTT2 deck tension tie released in 2009 is used for a 2009 IRC provision that addresses lateral loads on decks

- BPS ½ -6 bearing plate released in 2011 to address new provisions for shear wall bearing plates in the 2008 SDPWS, which is referenced in the 2009 and 2012 IBC

The latest example is the DTT1Z deck tension tie. Two of our engineers, Randy Shackelford and David Finkenbinder, attended the ICC hearings that resulted in the new 2015 IRC. As soon as a new provision was passed to provide an alternate 750-pound deck lateral load connection (submitted by Washington Assoc. of Building Officials, not Simpson Strong-Tie) we began working on a connector designed to do the job. After several months of R&D, field trials and new tooling, our presses began to stamp out the first production run of the DTT1Z to meet the 2015 IRC provision on December 30, 2014.

The IRC detail shows an ideal condition where the bottom of the deck joist lines up with the wall plates in the house. We tested this application, but we also wanted to support variations that may come up in the field. The results of this testing appear in our T-C-DECKLAT15 technical bulletin. We also tested the DTT1Z with our Strong-Drive® SDWH Timber-Hex HDG screw and our Titen HD® concrete screw anchor so it can be used in a variety of applications, including prescriptive wall bracing and (very) light shear walls. Many of these applications are covered in the code report (ER130) that was completed just this past week.

If you are interested in reading more about the new IRC deck provisions, Randy wrote about them in his Code Corner column in the current Structural Report and David wrote about them in this blog last August.

In case you are wondering how I respond when asked if we write the code, lately I have been answering it with another question: No, but do you know who is responsible for writing the code? My answer to this is “all of us.” If you don’t like what is in there now, work with an association that represents your interests (NCSEA for a lot of us) to submit a code-change proposal, or even submit one yourself. There is no guarantee it will get in, but if it involves a connection, I can guarantee we will get working on it right away!

Let us know if you see a need for a new connection product. If you already have a product idea and would like to work with us to develop it, you can more-formally submit it here.

Steel Strong-Wall® Footings Just got a Little Slimmer!

While 54 inches is a good height and will get you on most amusement park rides, what about this dimension for the width of a footing? We did some tests recently — actually a lot of tests — that answered that question.

Steel Strong-Wall® narrow panels are great for resisting high seismic or wind loads, but due to their narrow widths, their resulting anchor uplift forces can be rather hefty, requiring very large pad footings. How large? For Seismic Design Categories C-F, the largest cracked concrete solution per ACI318-11 Appendix D has a width of 54 inches and an effective embedment depth of 18 inches in order to ensure the anchor remains ductile. The overall length of this footing, as seen in Figure 1, can be up to 132 inches. While purely code driven, these solutions have historically presented challenges in the field. Most concrete contractors have to dig footings this size by hand. This often leads to discussions with their engineers about finding a better solution.

Simpson Strong-Tie has been studying cast-in-place anchorage extensively in recent years. Our research has been featured in a couple of blog posts: The Anchorage to Concrete Challenge – How Do You Meet It? and Podium Anchorage – Structure Magazine. Concrete podium slab anchorage was a multi-year test program that started with grant funding from the Structural Engineers Associations of Northern California for initial concept testing at Scientific Construction Laboratories Inc. and wrapped up with full-scale detailed testing completed at the Simpson Strong-Tie Tye Gilb Laboratory in Stockton, California. This joint venture studied the performance of anchorage reinforcement into thin podium deck slabs (10-14 inch) to resist the high overturning forces of continuous rod systems on 4-5-story mid-rise construction. The testing confirmed the need to comply with Appendix D requirements to prevent plastic hinging at anchor locations. Be on the lookout for an SE Blog post on that topic in the near future. Armed with what we learned, we decided to develop tested anchor reinforcing solutions for the Steel Strong-Wall.

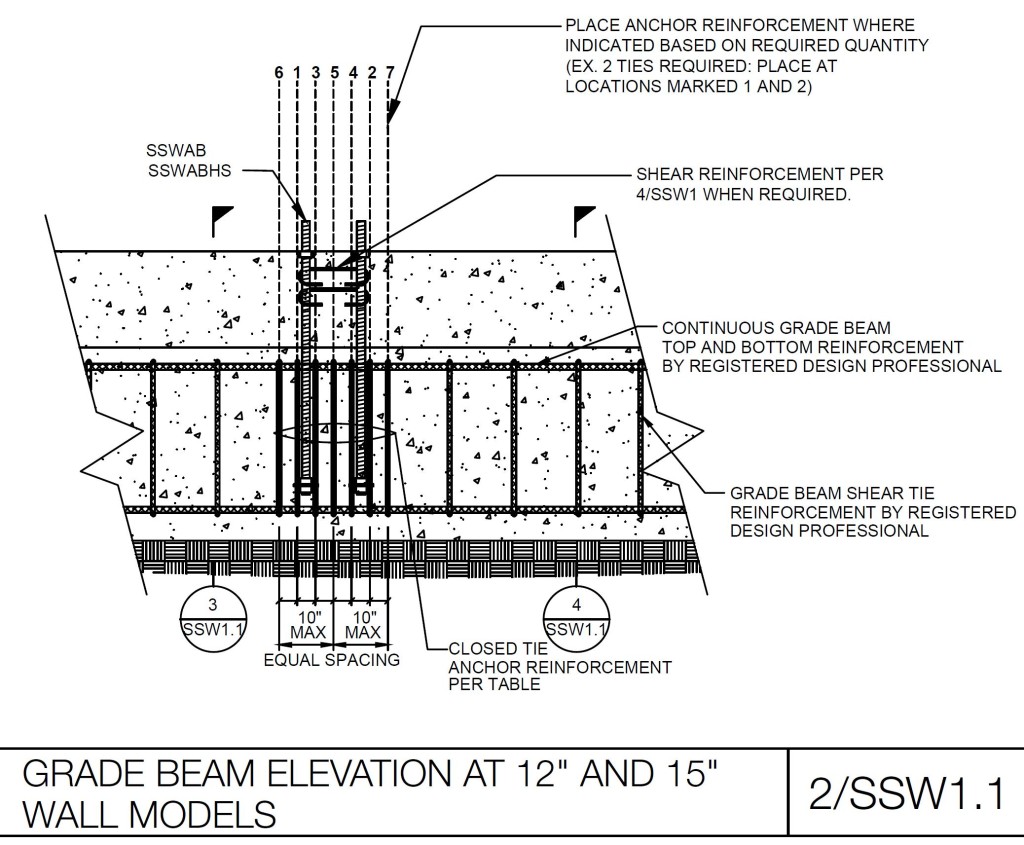

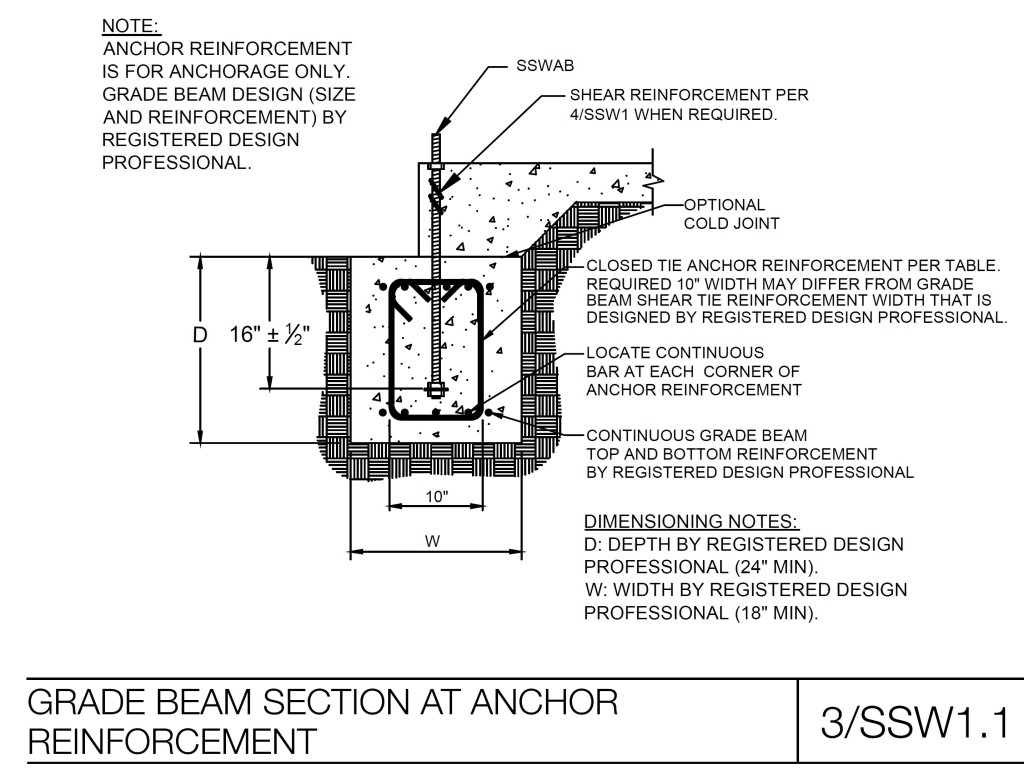

The newly developed anchor reinforcement solutions for grade beams are calculated in accordance with ACI318 Appendix D and tested to validate performance. Anchor reinforcement isn’t a new concept, as it’s been in ACI318 for some time. Essentially, anchor reinforcements transfer load from the anchor bolt to the reinforcing, which restrains the breakout cone from occurring. For the new grade beam details, the additional ties near the anchor are designed to resist the load from the anchor and are developed into the grade beam. The new details offer solutions with widths as narrow as 18 inches when anchor reinforcement is used.

Two details have been developed: one for the larger panels (SSW18, SSW21, SSW24) as shown in Detail 1/SSW1.1, and one for the smaller panels (SSW12, SSW15) as shown in Detail 2/SSW1.1. The difference between the two is the number of anchor reinforcement ties specified in Detail 3/SSW1.1. For SSW18, SSW21 and SSW24 panels (Detail 1/SSW1.1), the total number of reinforcement per anchor is specified. Due to their smaller sizes, the anchor reinforcement ties specified in Detail 2/SSW1.1 for the SSW12 and SSW15 panels are the total required per panel.

Validation Testing

From the concrete podium deck anchorage test program, we discovered that the flexural and shear capacity of the slab is critical to anchor performance and must be designed to exceed the demands created by the attached structure. For grade beams, this also holds true. In wind-load applications, this demand includes the factored demand from the Steel Strong-Wall. In seismic applications, our testing and analysis showed that achieving the anchor performance expected by Appendix D design methodologies requires the concrete member design strength to resist the amplified anchor design demand from Appendix D Section D.3.3.4.3.

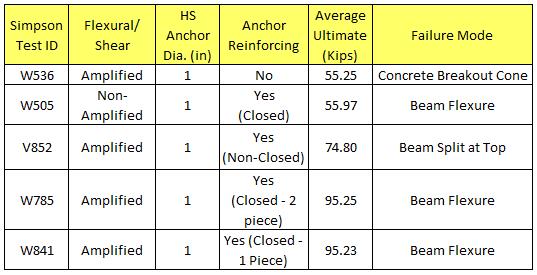

Validation testing was conducted to evaluate this concept. The test program consisted of a number of specimens with different configurations, including:

- Closed tie anchor reinforcement

- Non-closed tie u-stirrup anchor reinforcement

- Control specimen without anchor reinforcement

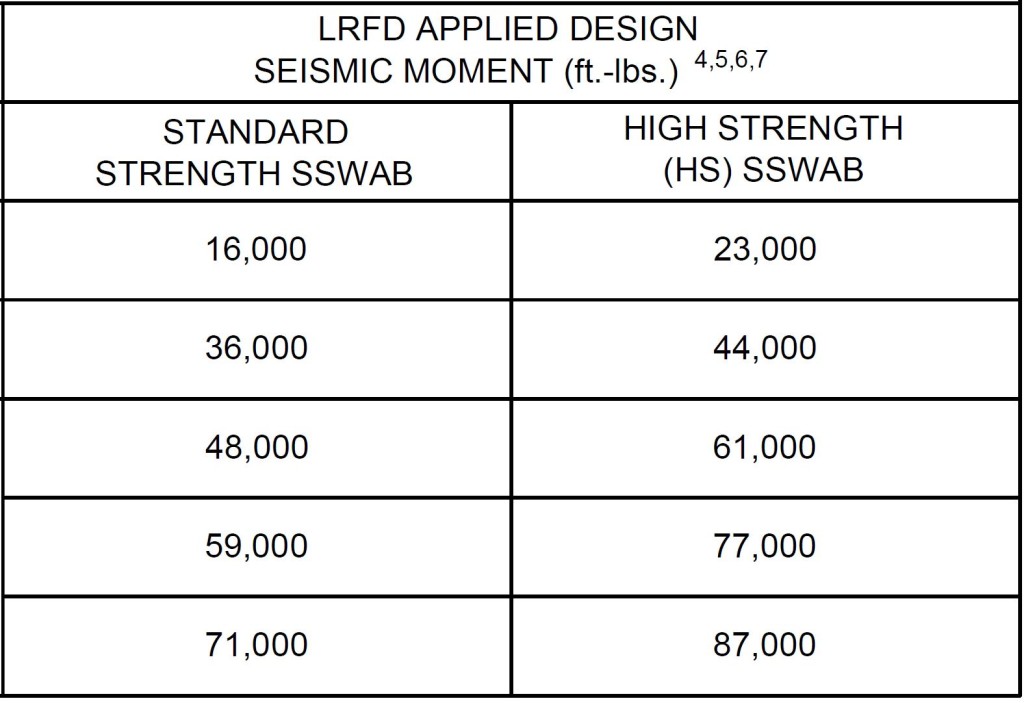

Flexural and shear reinforcement were designed to resist Appendix D amplified anchorage forces and were compared to test beams designed for non-amplified strength level forces. The results of the testing are shown in Figure 2. In the higher Seismic Design Categories (C-F), the anchor assembly must be designed to satisfy Section D.3.3.4.3 in ACI318-11 Appendix D. In accordance with D.3.3.4.3 (a), the concrete breakout strength needs to be greater than 1.2 times the nominal steel strength of the anchor, 1.2NSA. This requires a concrete breakout strength of 87 kips for a Steel Strong-Wall that uses a 1-inch high-strength anchor.

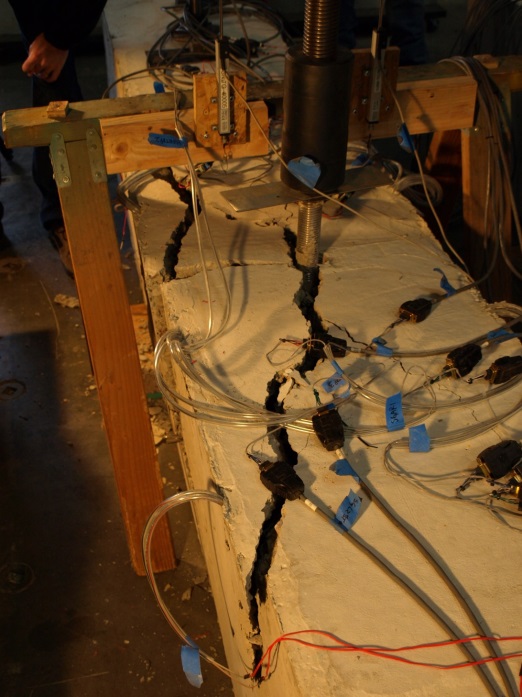

Grade beams without the anchor reinforcement detail and with flexural and shear reinforcement designed to the Appendix D amplified anchorage forces performed similar to those with closed-tie anchor reinforcement and flexural and shear reinforcements designed to the non-amplified strength level forces. Both, however, came up short of the necessary forces required by Section D.3.3.4.3 (a). From Test V852, we discovered that even though the flexural and shear reinforcement were designed with the amplified forces, the non-closed tie u-stirrups did not ensure the intended performance. From observation, the u-stirrups do not provide adequate confinement of the concrete and tend to open up under loading conditions, resulting in splitting of the beam at the top as can be seen in the photo.

Tests W785 and W841 resulted in the best performance. Both test specimens contained flexural and shear reinforcement designed for the amplified forces, as well as closed-ties. Two configurations were tested to study their performance — two piece closed-tie anchor reinforcement in W785 and a single piece closed-tie anchor reinforcement in Test W841. As seen in Figure 2, their performance was very similar, and met the requirements of Section D.3.3.4.3 (a). The closed-ties helped confine the concrete near the top of the beam, allowing the assembly to reach the expected performance load (See the photo below). It’s important to indicate the following specifics in the New Grade Beam Anchor Reinforcement Details:

- Anchor Reinforcement is #4 closed-ties

- SSWAB embedment depth is 16″ +/- ½” (as shown in Detail 3/SSW1.1). This is to ensure there is enough development length of the anchor reinforcement on both sides of the theoretical breakout surface as required by ACI318-11 D.5.2.9.

- The minimum distances from the anchor bolt plate washer to top and bottom of closed tie reinforcement are 13 inches and 5 inches respectively to ensure proper development above and below the concrete breakout cone (refer to Detail 3/SSW1.1).

- The spacing between the two vertical legs of the anchor reinforcement tie must be 10 inches apart. While this may differ from your shear reinforcement elsewhere in the grade beam, it ensures the reinforcement is located close enough to the anchor and adequate development length is provided.

- Flexural reinforcement (top and bottom) and shear reinforcement (ties throughout the grade beam length) are per the designer. Simpson Strong-Tie has provided information in Detail 3/SSW1.1 for the applicable minimum LRFD Applied Design Seismic Moment (See Figure 3) to make sure the grade beam design will at least resist the applied anchor forces. Project design loads not related to the Strong-Wall panel also should be considered and could control the grade beam design.

Simpson Strong-Tie is interested in hearing your thoughts on the new details. What is your opinion? How have the new details been received on your job sites?

Testing Fasteners for Deck Ledger Connections

This week’s blog post was written by Aram Khachadourian, R&D Engineer for Fastening Systems. Since joining Simpson Strong-Tie 14 years ago, he has designed and tested holdowns, hangers, truss connectors and anchor bolts. He has drafted numerous acceptance criteria as well as quality standards. His current focus is the development, testing and code approval of structural fasteners. Prior to his work at Simpson Strong-Tie, he spent his time designing steel buildings including strip malls, wineries and airplane hangars. Aram graduated from the University of California at Davis with a Civil Engineering degree, and is a registered professional engineer in California.

As we approach the beginning of spring, homeowners across the country are starting to turn their thoughts to the backyard and making plans to add a new deck for summer enjoyment.

As a contractor, designer, or homeowner, you want to know that this new deck will have the structural integrity to stand firm for many years and remain safe for everybody who will use it. While there are many aspects to building a safe, strong deck, today we are focusing on the attachment of the deck ledger to the structure.

Prior to 2009, numerous catastrophic deck failures attributed to improper deck ledger attachments demonstrated the need for building code guidance. A calculated solution was overly conservative because the sheathing layer, typically present between the deck ledger and the structure’s band joist, was considered to be a gap in the connection. A prescriptive approach to deck ledger attachments was finally introduced in the 2009 International Residential Code (IRC). Table R502.2.2.1 provided fastener spacings for ½”-diameter lag screws and bolts. These values were based on testing conducted by researchers at Virginia Tech and Washington State University.

The tests included a variety of band joist types, with pressure-treated Hem-Fir as the deck ledger material. The deck ledger was tested at high moisture content to represent a wet, worst-case field condition. The test assembly had a load bar spanning two joists that were attached to the deck ledger with joist hangers. The ledger was attached through the sheathing to the rim board. Only the rim board was supported by the test frame. The average ultimate load was divided by a factor-of-safety of 3 and then further divided by the load duration coefficient of 1.6 to achieve an allowable load. These values were then applied to a deck live load of 40 psf plus a deck dead load of 10 psf to derive allowable fastener on-center spacings for various joist spans.

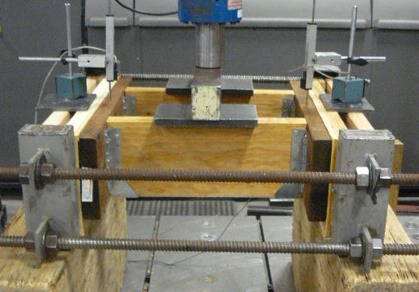

When Simpson Strong-Tie began to rate fasteners for ledger connections, we used a similar method of testing and analysis. However, we incorporated a few changes. One of the changes we implemented was a symmetric test set-up. The original test assembly had a ledger on one end of the joists and a support member as the boundary condition on the other. We put a ledger at each end of the joists so stiffness differences in the supports would not affect the test results. We also chose a larger factor-of-safety of 3.2 (instead of 3.0) to maintain consistency with calculation of fastener allowable loads in other applications. In order to provide our customers with a broader range of construction options, we tested many typical rim board and ledger materials, and we ran tests with single and double ledgers. You can see an example of a typical test set up here:

We have tested many Simpson Strong-Tie® Strong-Drive® fasteners for ledger applications including the SDWS Timber screw (SDWS22DB), SDWH Timber-Hex SS screw (SDWH-SS), SDWH Timber-Hex screw (SDWH19DB), and SDS Heavy-Duty Connector screw (SDS). We also have information regarding ledgers attached to studs and ledgers fastened over gypsum board. You can find all of this information in our latest fastener catalog.

One final construction tip – deck ledgers can fail due to cross-grain tension. This occurs when the joist hangers are attached to the deck ledger near the bottom of the ledger, but the fasteners holding the ledger to the building are near the top of the ledger. To prevent cross-grain tension failure, place the joist hangers so at least half of the ledger fasteners are below the joist hanger line.

Take a look through the various ledger options in our fastener catalog, and if we don’t address your condition, let us know. As always, call us in the Engineering Department if you have questions.

Please share your feedback in the comments area below.

Part II: Tensile Performance of Simpson Strong-Tie® SET-XP® Adhesive in Reinforced Brick – Test Results

This post is the second of a two-part series on the results of research on anchorage in reinforced brick. The research was done to shed light on what tensile values can be expected for adhesive anchors. In last week’s post, we covered the test set-up. This week, we’re taking a look at our results and findings.Continue Reading