This post was co-written by Simpson Engineer Randy Shackelford and AWC Engineer Phil Line.

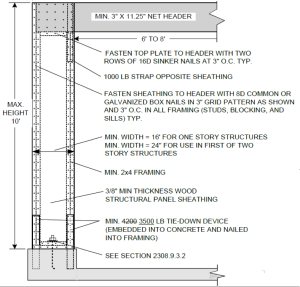

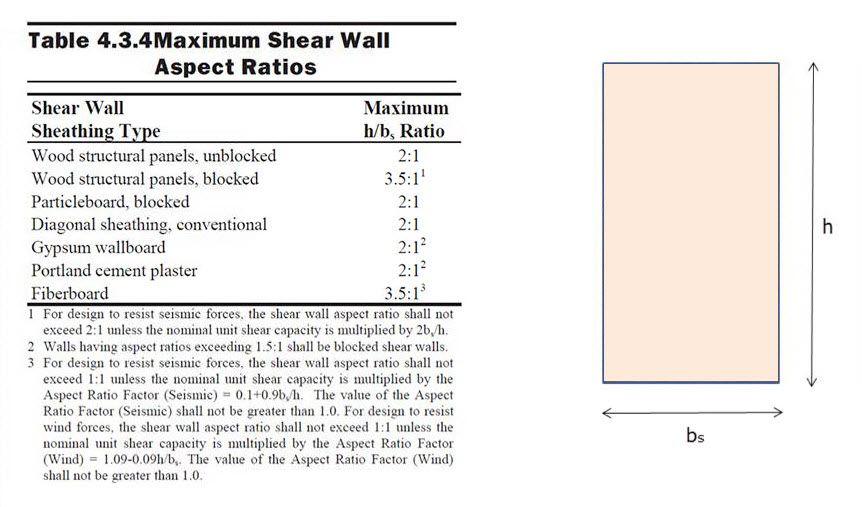

The 2015 International Building Code references a newly updated 2015 Edition of the American Wood Council Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic standard (SDPWS). The updated SDPWS contains new provisions for design of high aspect ratio shear walls. For wood structural panels shear walls, the term high aspect ratio is considered to apply to walls with an aspect ratio greater than 2:1.

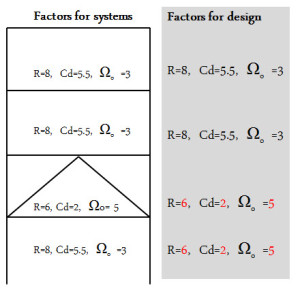

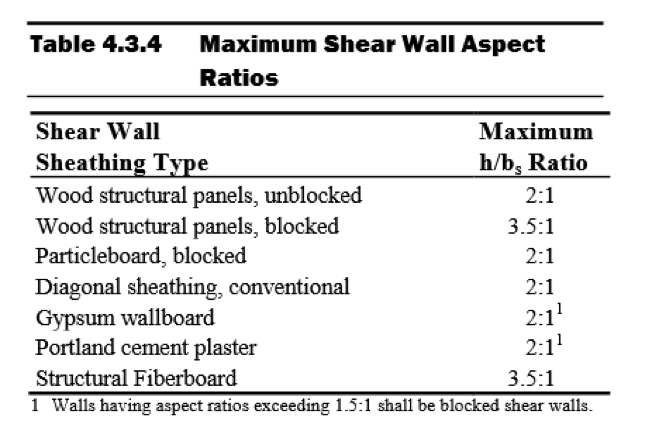

In the 2015 SDPWS, reduction factors for high aspect ratio shear walls are no longer contained in the footnotes to Table 4.3.4 (See Figure 2). Instead, these factors are included in new provisions accounting for the reduced strength and stiffness of high aspect ratio shear walls.

Deflection Compatibility – Calculation Method

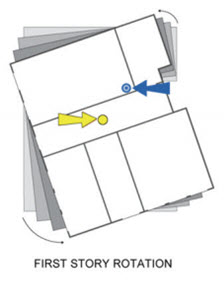

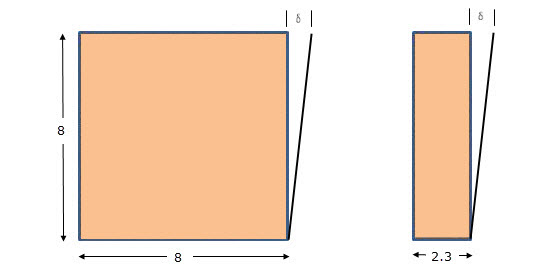

New Section 4.3.3.4.1 states that “Shear distribution to individual shear walls in a shear wall line shall provide the same calculated deflection, δsw, in each shear wall.” Using this equal deflection calculation method for distribution of shear, the unit shear assigned to each shear wall within a shear wall line varies based on its stiffness relative to that of the other shear walls in the shear wall line. Thus, a shear wall having relatively low stiffness, as is the case of a high aspect ratio shear wall within a shear wall line containing a longer shear wall, is assigned a reduced unit shear (see Figure 3).

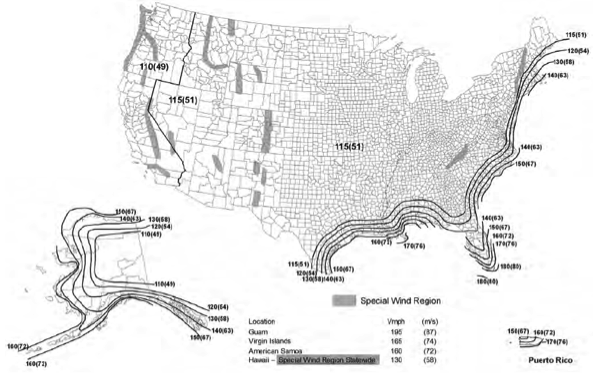

In addition, Section 4.3.4.2 contains a new aspect ratio factor, 1.25 – 0.125h/bs, that specifically accounts for the reduced unit shear capacity of high aspect ratio shear walls. The strength reduction varies linearly from 1.00 for a 2:1 aspect ratio shear wall to 0.81 for a 3.5:1 aspect ratio shear wall. Notably, this strength reduction applies for shear walls resisting either seismic forces or wind forces. For both wind and seismic, the controlling unit shear capacity is the smaller of the values from strength criteria of 4.3.4.2 or deflection compatibility criteria or 4.3.3.4.1.

Deflection Compatibility – 2bs/h Adjustment Factor Method

The 2bs/h factor, previously addressed by footnote 1 of Table 4.3.4, is now an alternative to the equal deflection calculation method of 4.3.3.4.1 and applies to shear walls resisting either wind or seismic forces. This adjustment factor method allows the designer to distribute shear in proportion to shear wall strength provided that shear walls with high aspect ratio have strength adjusted by the 2bs/h factor. The strength reduction varies linearly from 1.00 for 2:1 aspect ratio shear walls to 0.57 for 3.5:1 aspect ratio shear walls. This adjustment factor method provides roughly similar designs to the equal deflection calculation method for a shear wall line comprised of a 1:1 aspect ratio wall segment in combination with a high aspect ratio shear wall segment.

In prior editions of SDPWS, a common misunderstanding was that the 2bs/h factor represented an actual reduction in unit shear capacity for high aspect ratio shear walls as opposed to a reduction factor to account for stiffness compatibility. The actual reduction in unit shear capacity of high aspect ratio shear walls is represented by the factor, 1.25 – 0.125h/bs, as noted previously. The 2bs/h factor is the more severe of the two factors and is not applied simultaneously with the 1.25-0.125h/bs factor.

What are the major implications for design?

- For seismic design, the 2bs/h factor method continues unchanged, but is presented as an alternative to the equal deflection method in 4.3.3.4.1 for providing deflection compatibility. The equal deflection calculation method can produce both more and less efficient designs that may result from the 2bs/h factor method depending on the relative stiffness of shear walls in the wall line. For example, design unit shear for shear wall lines comprised entirely of 3.5:1 aspect ratio shear walls can be as much as 40% greater (i.e. 0.81/0.57=1.42) than prior editions if not limited by seismic drift criteria.

- For wind design, high aspect ratio shear wall factors apply for the first time. For shear walls with 3.5:1 aspect ratio, unit shear capacity is reduced to not more than 81% of that used in prior editions. The actual reduction will vary by actual method used to account for deflection compatibility.

- The equal deflection calculation method is sensitive to many factors in the shear wall deflection calculation including hold-down slip, sheathing type and nailing, and framing moisture content. The familiar 2bs/h factor method for deflection compatibility is less sensitive to factors that affect shear wall deflection calculations and in many cases will produce more efficient designs.

As the 2015 International Building Code is adopted in various jurisdictions, designers will need to be aware of these new requirements for design of high aspect ratio shear walls. The 2015 SDPWS also contains other important revisions that designers should pay attention to. The American Wood Council provides a read-only version of the standard on their website that is available free of charge.

Please contribute your thoughts to these new requirements in the comments below.