All of us here at Simpson Strong-Tie hope you had a happy and successful 2014. It seems that the folks at the International Code Council had a good year. True to their plan, the 2015 editions of the International Codes were published during the summer so that they are ready for adoption in 2015.

Simpson Strong-Tie was tracking a number of issues during the development of the 2015 International Building Code and International Residential Code. Here is a summary of some of the significant changes that users will see in the 2015 International Building Code (IBC).

Simpson Strong-Tie was tracking a number of issues during the development of the 2015 International Building Code and International Residential Code. Here is a summary of some of the significant changes that users will see in the 2015 International Building Code (IBC).

One significant change affecting Simpson Strong-Tie was the removal of the requirements for evaluation of joist hangers and similar devices from Chapter 17, and the revision of Sections 2303.5 and 2304.10.3 to reference ASTM D 7147 as the test standard for joist hangers.

Since the primary reference standard for design in Chapter 16, ASCE 7-10 has not changed; there were not a lot of significant changes in that chapter. The definitions of “Diaphragm, rigid” and “Diaphragm, flexible” were deleted from Chapter 2, and a sentence was added to 1604.4 stating when a diaphragm can be considered rigid, along with a reference to ASCE 7 for determining when designs must account for increased forces from torsion due to eccentricity in the lateral force resisting system.

In Chapter 19, significant improvements were made to the sections that modify ACI 318 so that the IBC and the standard are coordinated, correcting the problems in the 2012 IBC. In addition, Sections 1908 (ASD design of anchorage to concrete) and 1909 (strength design of anchorage to concrete) were deleted to remove any conflict with ACI 318 anchor design methods.

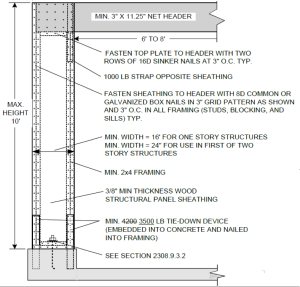

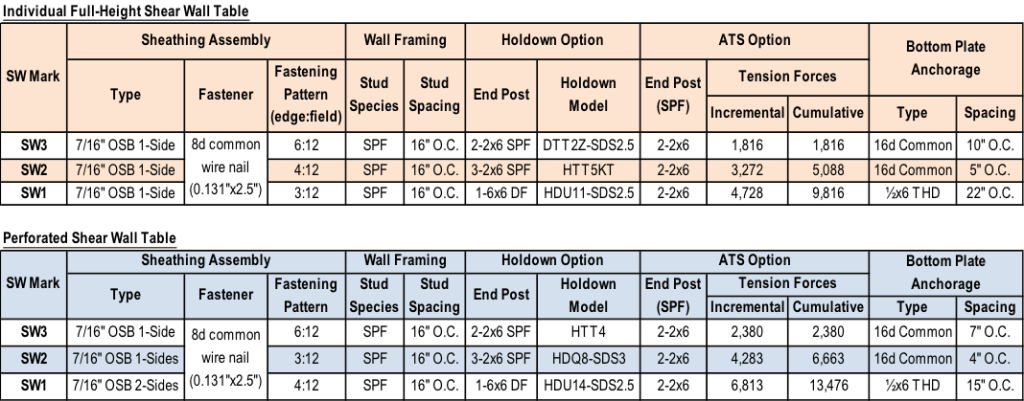

In Chapter 23, a new section was added to address cross-laminated timber, requiring that they be manufactured and identified as required in APA PRG 320. The wood framing fastening schedule was completely reorganized to make it easier to use and the requirements for protection of wood from decay and termites were rewritten. Section 2308 on Conventional Light-Frame Construction was completely reorganized with significant revisions to the wall bracing section. As discussed in an earlier blog post, the holdown requirement for the portal frame with holdowns (now called PFH bracing method in the 2015 IBC) has been reduced from a required capacity of 4,200 pounds to 3,500 pounds.

For designers, some of the most significant changes are in Chapter 35, which lists referenced standards. Some major standards that were updated for this edition of the IBC include ACI318-14, ACI530/530.1-13, several AISI standards (S100-12, S200-12, S214-12, and S220-11), several new and revised ASCE standards (8-14, 24-13, 29-14, 49-07, and 55-10), almost all the AWC standards (WFCM-2015, NDS-2015, STJR-2015, PWF-2015 and SDPWS-2015), AWS D1.4/D1.4M-2011, most NFPA standards (too many to list), PTI DC-10.5-12, SBCA FS 100-12 and TPI 1-14.

Kudos to the American Wood Council. They have posted view-only versions of all their referenced standards online, so designers do not have to buy new editions every time the code changes. AISI also enables one to download PDFs of the framing standards at www.aisistandards.org.

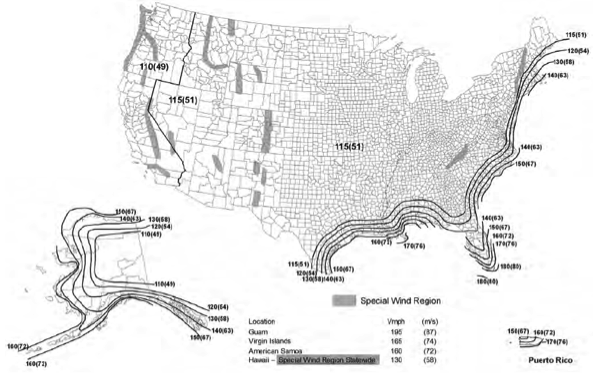

Finally, a couple of ICC Standards were updated to new versions that are referenced in the IBC: ICC-500-14, ICC/NSSA Standard on the Design and Construction of Storm Shelters; and ICC 600-14, Standard for Residential Construction in High-Wind Regions.

A future blog post will cover significant changes in the 2015 IRC. Please share your comments below.