Truss repair is one of the most frequently asked about truss topics. Not surprisingly, when we asked for suggested truss topics in a truss blog earlier this year, truss repair information made the list. Because the summer months bring about a peak in new construction – and plenty of truss repairs to go along with it – the beginning of June is the perfect time to visit this topic.

From trusses that get dropped or cut/drilled/notched at the jobsite, to homeowners who want to modify their existing trusses to add a skylight or create attic space to fire-damaged trusses, a multitude of scenarios fall under the broad topic of truss repair. Today’s post focuses on various references and resources that can provide some assistance. But first it helps to break down the broad “truss repair” topic into more manageable-sized categories.

New Construction vs. Recent Construction vs. Old Construction

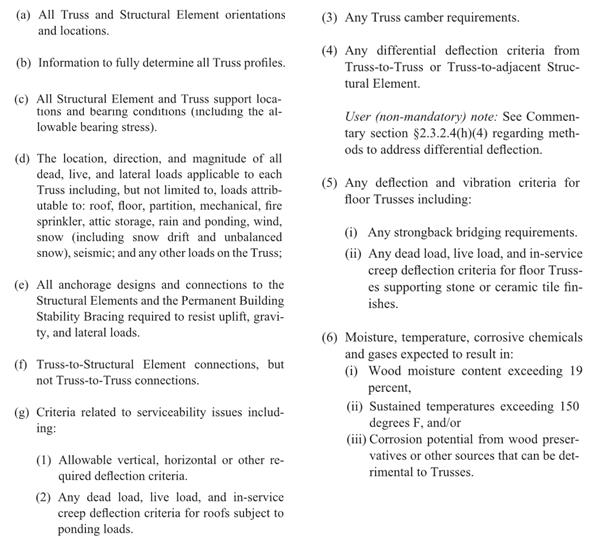

By far, the easiest type of truss repair is new construction, when the trusses either haven’t been installed yet or are still in the process of being installed. Whether the repair is relatively simple (e.g. a broken web) or a little more complicated (e.g. the trusses need to be stubbed), the beauty of new truss construction is that the truss manufacturer – and truss Designer – can be contacted and help with the repair. The truss Designer can easily open up the truss designs in the truss design software, quickly evaluate the trusses for the appropriate field conditions and issue a repair.

A good reference related to truss repairs for new truss construction is the Building Component Safety Information (BCSI) booklet jointly produced by SBCA and TPI. Section B5 of the BCSI booklet, which is also available as a stand-alone summary sheet, covers Truss Damage, Jobsite Modifications & Installation Errors. This field-guide document describes the steps to take when a truss at the jobsite is damaged, altered or improperly installed, common repair techniques, and the information to provide to the truss manufacturer when a truss is damaged, which will assist in the repair process.

The next easiest truss type to repair is recent construction, where the trusses were constructed recently enough that: a) the truss plates are easy to identify, and b) the truss design drawings may even still be available. In these cases, design professionals other than the original truss Designer may be contacted to repair the trusses. For some types of repairs, the design professional can work off the truss design drawing to design the repair. Other times it might be necessary to model and analyze the truss using structural design software; alternatively, a truss manufacturer can be contacted to model the truss in their truss design software for a fee.

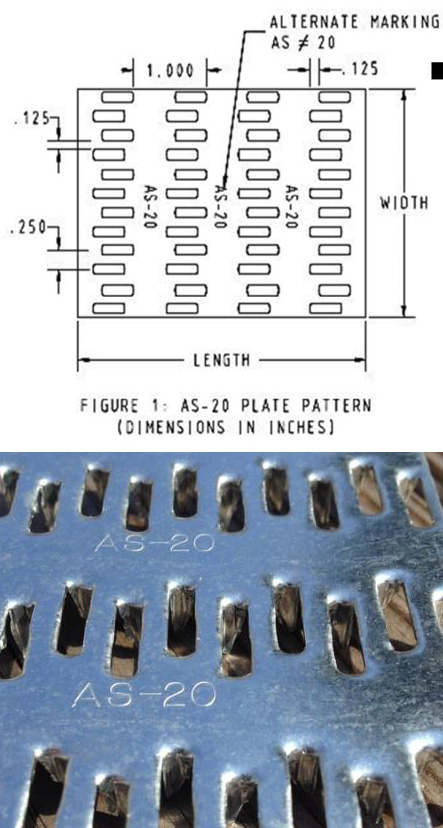

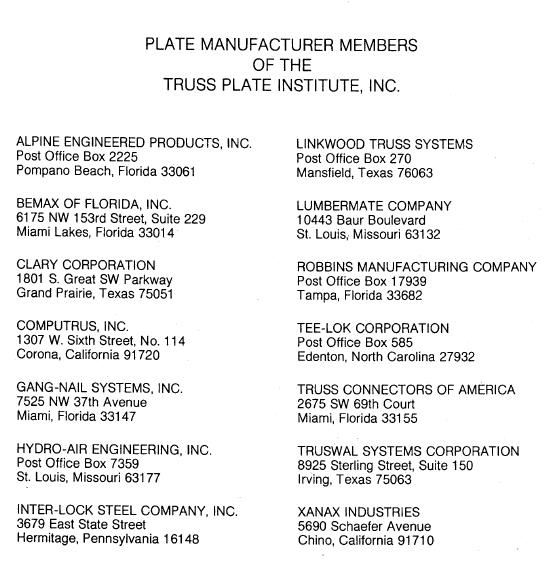

Often, the design professional wants to know the design values for the truss plates that were used to construct the truss. If there are truss design drawings available, they will indicate which truss plates were used in the design, and then the truss plate manufacturer can be contacted for more information. It is also easy to search for the truss plate code reports online (for instance, check icc-es.org). If no truss design drawing is available, there is still a way to identify the truss plates. Currently, there are only five major truss plate manufacturers in the United States, and they are listed on the Truss Plate Institute website. That makes identification of the truss plates used in recently constructed trusses easier because all of the current manufacturers’ plates will have markings that are described in their code reports. (Note that there are also a couple of truss manufacturers in the U.S. that manufacture their own truss plates.)

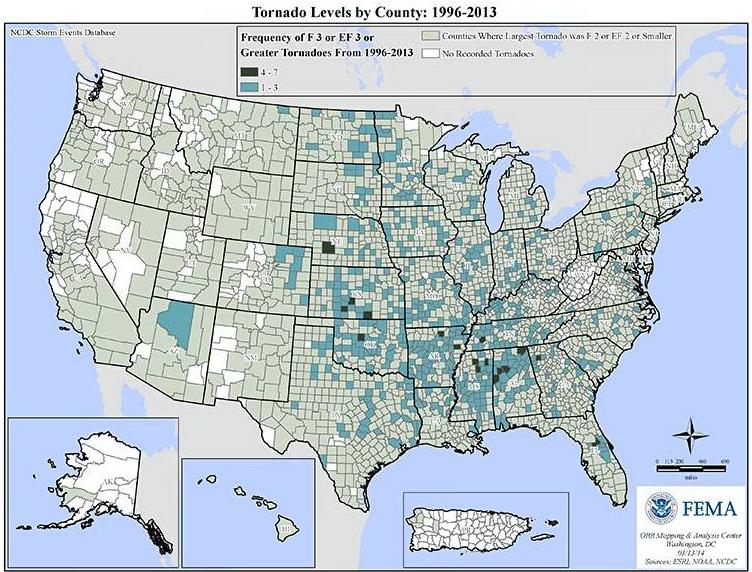

Finally, the most challenging type of trusses for truss repairs are those found in older buildings. Design professionals involved in these types of repair often aren’t sure where to start. Truss design drawings are often not available, and the act of trying to identify the truss plate manufacturer is challenging at best, unsuccessful at worst. As a point of reference, there were 14 truss plate manufacturers that were TPI members in 1987 (see image below), and only one of those companies is still in the current list of five companies. Therefore, the truss plates found in a truss built around 1987 will be difficult to identify. One option is to contact TPI and see if they can point you in the right direction.

Simple vs. Complex Repairs

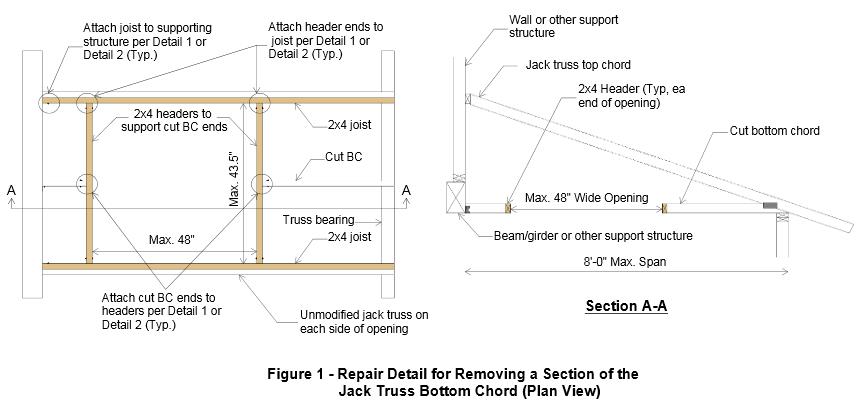

Another way to break down truss repairs is to divide them into easy and challenging repairs. People often ask for “standard” truss repair details. Unfortunately, standard details only address the simplest types of repair; and those usually aren’t the types of repair that are asked about. Details simply cannot cover the wide range of truss configurations and every type of repair situation.

With the exception of simple repairs, most truss repairs rely heavily on the judgment and experience of the design professional doing the repair. And because there are not entire textbooks devoted to truss repair (that I am aware of, anyway), Designers must pull from a variety of resources, both to learn more about truss repair and to design the repair. For repairs using plywood or OSB gussets, the APA Panel Design Specification is a must-have reference. Some people prefer to use dimension lumber scabs for their repairs, whenever possible, simply because they are more familiar with dimension lumber (and the NDS) than they are with Plywood/OSB or the APA Panel Design Specification.

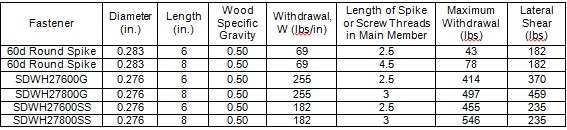

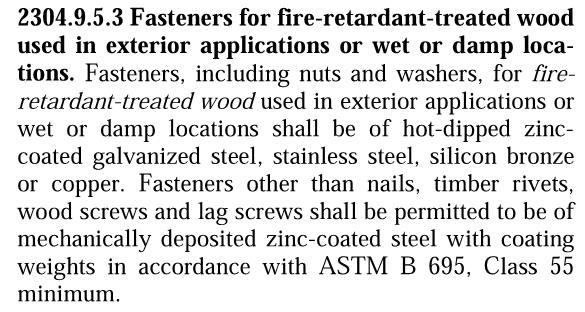

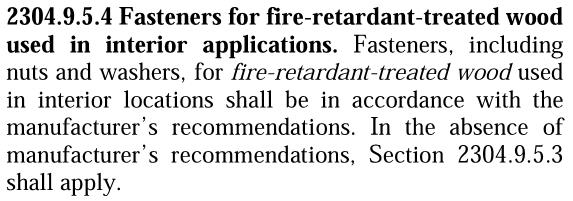

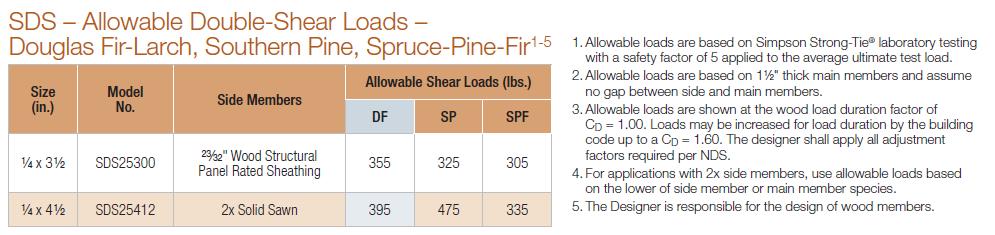

Next, the fasteners for the repair must be selected and the allowable loads determined. For nail design values, I am a big fan of the American Wood Council’s Connection Calculator, which provides allowable nail shear values for just about any combination of main and side members that you can think of, including OSB and plywood side members – particularly handy for truss repairs. For more complex repairs, and especially repairs involving higher forces, an excellent fastener choice is a structural wood screw such as our Strong-Drive® SDS or SDW screws. When I worked in the R&D department at Simpson Strong-Tie, a frequently asked question was whether we had double-shear values for our SDS screws. The questions always seemed to come from Designers who wanted them for truss repairs. Fortunately, we do have double-shear values for our SDS screws.. You can find them on page 319 of our Fastening catalog.

The Strong-Drive SDW screw was developed after the SDS screw, and while there are currently no double-shear values for the SDW, it is still another good option for repairs.

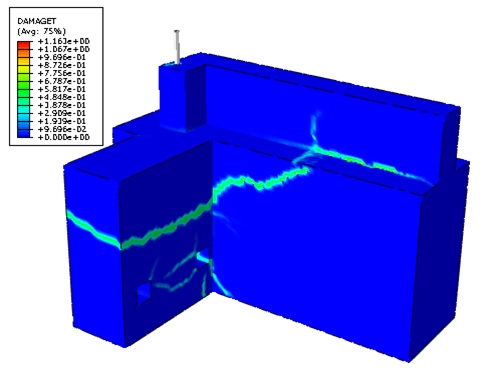

Fire-Damaged Trusses and Truss Collapses

These situations are in a category by themselves because they go beyond even the most complex repairs involving a major modification to the truss. The biggest difference is that the latter case involves mostly known facts and perhaps some conservative assumptions, whereas damage due to fire or collapse includes many unknowns. Most of the truss Designers I have spoken to about truss damage due to fire or truss collapse often recommend replacement of the trusses rather than repair because it is usually too difficult to quantify the damage to the lumber and/or joints. In fires, there can be “hidden” damage due to the sustained high temperatures, while the truss appears to have no visible damage. Likewise, in a truss collapse, not only may there be too many breaks in the trusses involved in the collapse, but there may also be trusses that suffered severe stresses during the collapse and have damage that is not visible. To attempt a repair in either of these cases often requires an inspection at the jobsite, and the result may still end up being replacement of some or all of the trusses. Therefore, the cost of a full-blown inspection should be weighed against the cost of replacing the trusses.

The Structural Building Components Association website has a page with information pertaining to fire issues. It includes a couple of documents related to fire damage that are worth checking out.

Beyond the Blog: Where to Get More Truss Repair Information

The best bet for getting practical design information related to truss repairs is to keep an eye out for short courses, workshops or seminars. ASCE has hosted a Truss Repair Seminar (Evaluating Damage and Repairing Metal Plate Connected Wood Trusses) in the past and may very well offer something like it again. Virginia Tech recently hosted a short course on Advanced Design Topics in Wood Construction Engineering, which included a section on Wood Truss Repair Design Techniques.

What other references or resources for truss repair do you use? Are there any upcoming truss repair courses that you know of? Please let us know in the comments below!