This year, the new 5th Edition of the Florida Building Code was released and is now in effect statewide. First printed in 2002, the Florida Building Code was developed as part of Florida’s response to the destruction caused by Hurricane Andrew and other hurricanes in the state.

Another component, which I would like to take a closer look at in today’s post, is a separate Florida Product Approval system designed to be a single source for approval of construction products for manufacturers, Designers and code enforcers. This single system streamlines the previous approach of different procedures for product approval in different jurisdictions. While statewide approval is not required, many jurisdictions, manufacturers and specifiers prefer using the statewide system to the alternative, which is called local product approval. To ensure uniformity of the state system, Florida law compels local jurisdictions to accept state-approved products without requiring further testing and evaluation of other evidence, as long as the product is being used consistent with the conditions of its approval.

The rules of the Florida Product Approval system are in Florida Rule 61G20-3. Here is some basic information about Florida Product Approval.

The Florida Product Approval system is only available for “approval of products and systems, which comprise the building envelope and structural frame, for compliance with the structural requirements of the Florida Building Code.” So users will only find certain types of products approved there. However, if you work in areas where design for wind resistance is required, the Florida system can be a gold mine of information for tested, rated and evaluated products. Not only will you find products like Simpson Strong-Tie connectors with our ICC-ES and IAPMO UES evaluation reports, but thousands of other tested and rated windows, doors, shutters, roof covering materials and other products that don’t typically get evaluation reports from national entities. The specific categories of products covered under the Florida system are exterior doors, impact protective systems, panel walls, roofing, shutters, skylights, structural components and windows.

To protect consumers, a recent law passed in Florida states that a product may not be advertised, sold or marketed as offering protection from hurricanes, windstorms or wind-borne debris unless it has either State Product Approval or local product approval. Selling unapproved products in this way is considered a violation of the Florida Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices Act.

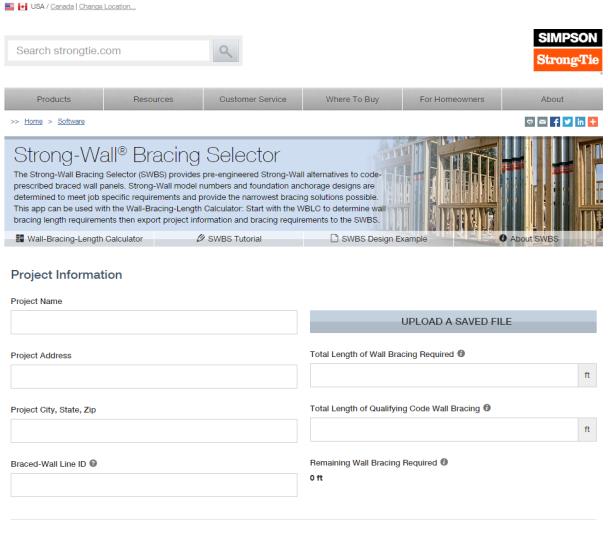

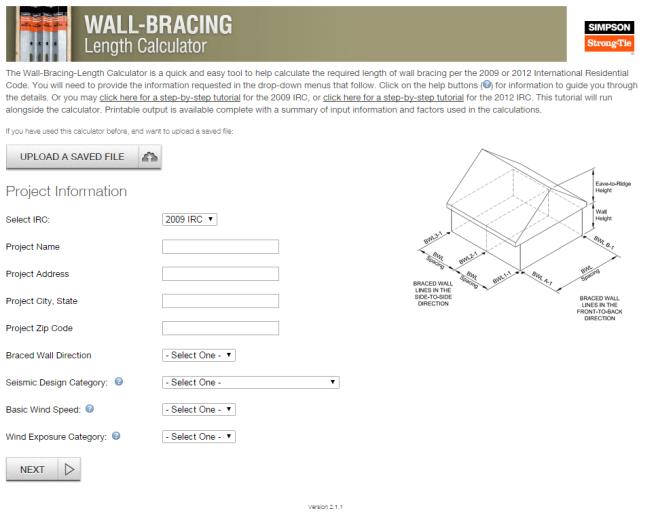

Once a manufacturer understands the process for achieving a statewide approval, it is not difficult to achieve, but it can be expensive. The manufacturer must apply on the State of Florida Building Code Information System (BCIS) website at www.floridabuilding.org. To prove compliance with the code, the manufacturer must upload either a test report, a product certification from an approved certification entity, an evaluation report from a Florida Professional Engineer or Architect, or an evaluation report from an approved evaluation entity (ICC-ES, IAPMU UES, or Miami-Dade County Product Control). Then, the manufacturer must hire an independent validator to review the application to ensure it complies with the Product Approval Rule and that there are no clerical errors. Finally, once the validation is complete, staff from the Department of Business and Professional Regulation reviews the application. Depending on the method used to indicate code compliance, the application may be approved at that time or it may have to go through additional review by the Florida Building Commission.

Here are several ways to find out if a product is approved.

- For Simpson Strong-Tie products, we maintain a page on www.strongtie.com that lists our Florida Product Approvals.

- The Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation maintains a page where users can search Product Approvals by categories such as manufacturer, category of product, product name, or other attributes such as impact resistance or design pressure.

- A third-party group we work with has created a website called www.ApprovalZoom.com that lists various product evaluations and product approvals. In addition to listing Florida Product Approvals, they also list ICC-ES evaluation reports, Miami-Dade County Notices of Acceptance, Texas Department of Insurance Approvals, Los Angeles Department of Building Safety Approvals, AAMA certifications and Keystone certifications among others.

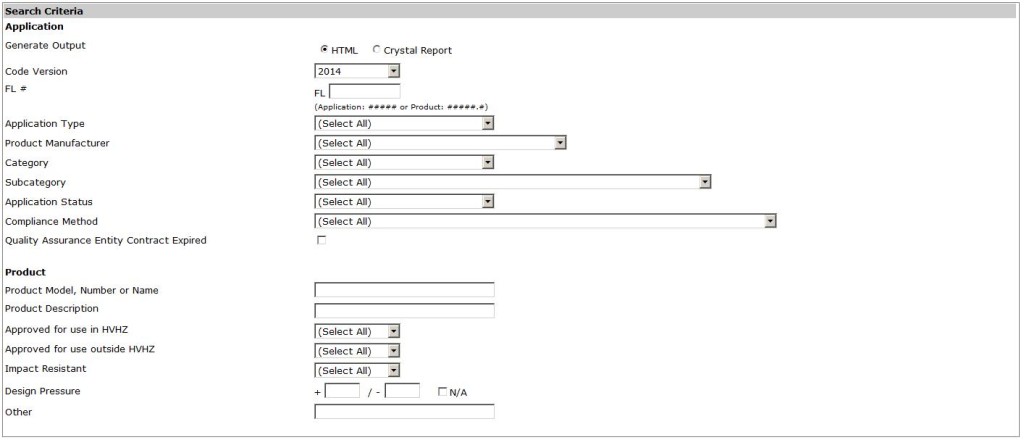

The process for searching for approved products on the Florida BCIS is fairly simple.

- Go to www.floridabuilding.org

- On the menu on the left side of the page, click on Product Approval. Or, click this link to go directly to the search page.

- On the Product Approval Menu, click on Find a Product or Application. Note that at this location you can also search for approved organizations such as certification agencies, evaluation entities, quality assurance entities, testing laboratories and validation entities.

- Ensure the proper Code Version is shown. The current 2014 Florida Code is based on the 2012 International Codes.

- At this point, several options can be searched. You can search for all approvals by a specific product manufacturer or a certain type of building component by searching Category and Subcategory, or if searching for a specific product, by entering the manufacturer’s name and the product name.

I hope you find the information contained in the Florida Product Approval system useful. Do you have other needs to find approved products?