This week’s blog post was written by Aram Khachadourian, R&D Engineer for Fastening Systems. Since joining Simpson Strong-Tie 14 years ago, he has designed and tested holdowns, hangers, truss connectors and anchor bolts. He has drafted numerous acceptance criteria as well as quality standards. His current focus is the development, testing and code approval of structural fasteners. Prior to his work at Simpson Strong-Tie, he spent his time designing steel buildings including strip malls, wineries and airplane hangars. Aram graduated from the University of California at Davis with a Civil Engineering degree, and is a registered professional engineer in California.

As we approach the beginning of spring, homeowners across the country are starting to turn their thoughts to the backyard and making plans to add a new deck for summer enjoyment.

As a contractor, designer, or homeowner, you want to know that this new deck will have the structural integrity to stand firm for many years and remain safe for everybody who will use it. While there are many aspects to building a safe, strong deck, today we are focusing on the attachment of the deck ledger to the structure.

Prior to 2009, numerous catastrophic deck failures attributed to improper deck ledger attachments demonstrated the need for building code guidance. A calculated solution was overly conservative because the sheathing layer, typically present between the deck ledger and the structure’s band joist, was considered to be a gap in the connection. A prescriptive approach to deck ledger attachments was finally introduced in the 2009 International Residential Code (IRC). Table R502.2.2.1 provided fastener spacings for ½”-diameter lag screws and bolts. These values were based on testing conducted by researchers at Virginia Tech and Washington State University.

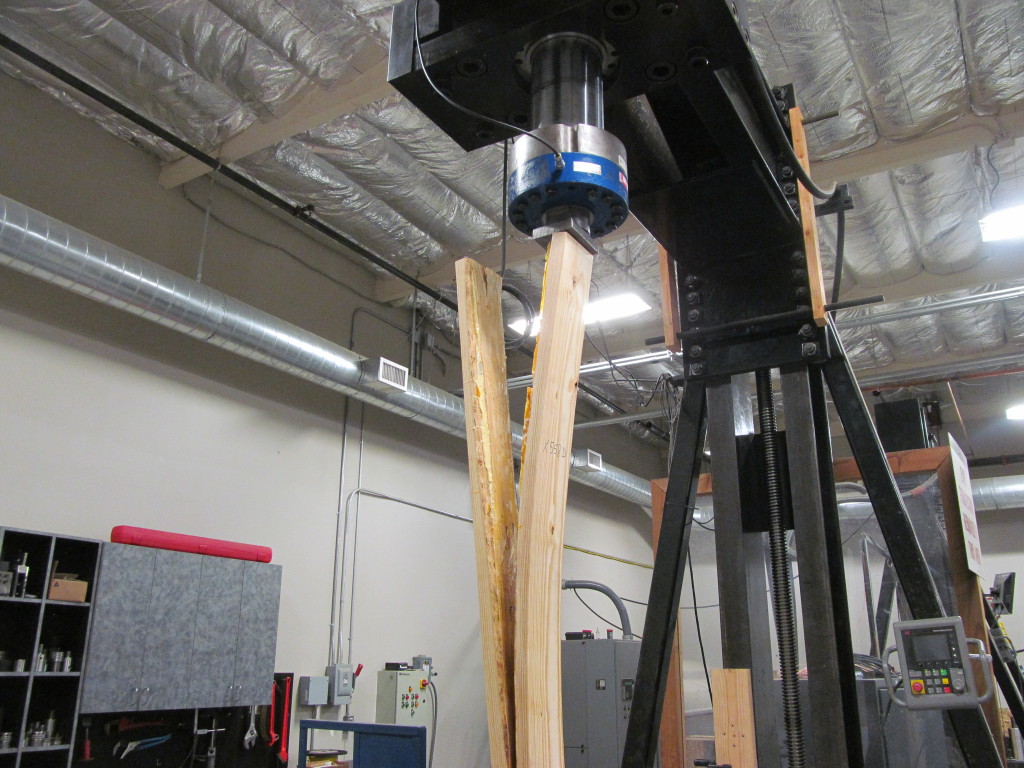

The tests included a variety of band joist types, with pressure-treated Hem-Fir as the deck ledger material. The deck ledger was tested at high moisture content to represent a wet, worst-case field condition. The test assembly had a load bar spanning two joists that were attached to the deck ledger with joist hangers. The ledger was attached through the sheathing to the rim board. Only the rim board was supported by the test frame. The average ultimate load was divided by a factor-of-safety of 3 and then further divided by the load duration coefficient of 1.6 to achieve an allowable load. These values were then applied to a deck live load of 40 psf plus a deck dead load of 10 psf to derive allowable fastener on-center spacings for various joist spans.

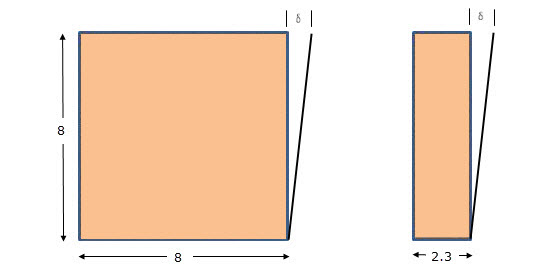

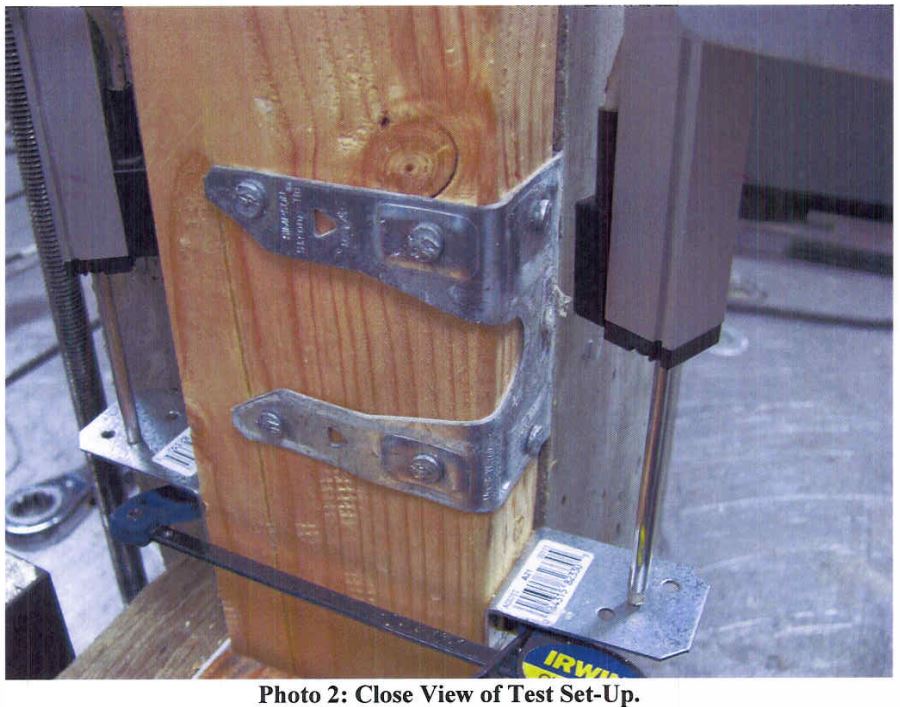

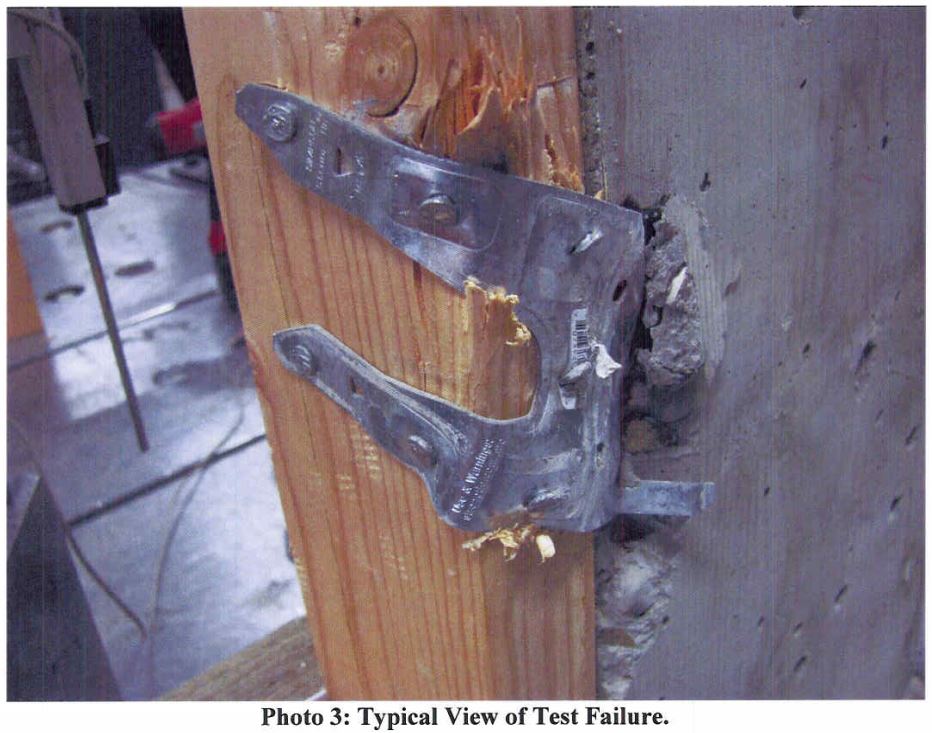

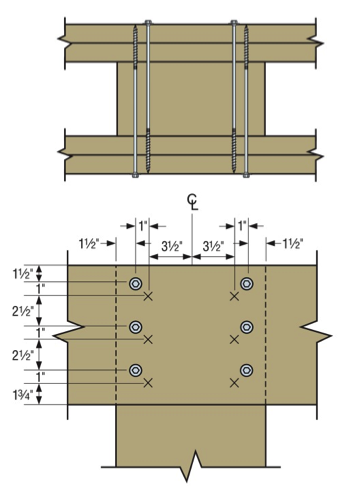

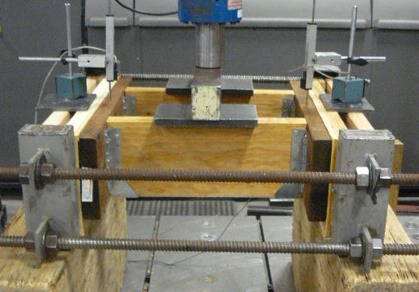

When Simpson Strong-Tie began to rate fasteners for ledger connections, we used a similar method of testing and analysis. However, we incorporated a few changes. One of the changes we implemented was a symmetric test set-up. The original test assembly had a ledger on one end of the joists and a support member as the boundary condition on the other. We put a ledger at each end of the joists so stiffness differences in the supports would not affect the test results. We also chose a larger factor-of-safety of 3.2 (instead of 3.0) to maintain consistency with calculation of fastener allowable loads in other applications. In order to provide our customers with a broader range of construction options, we tested many typical rim board and ledger materials, and we ran tests with single and double ledgers. You can see an example of a typical test set up here:

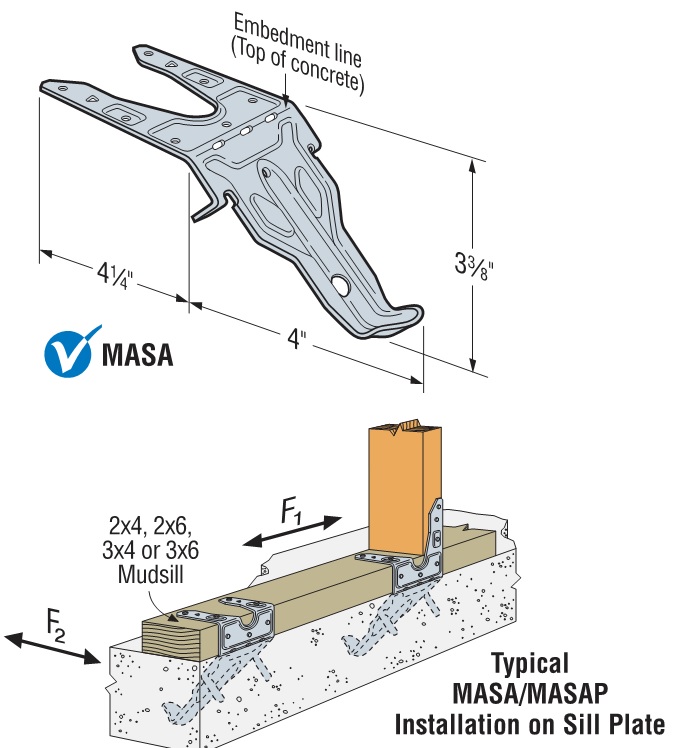

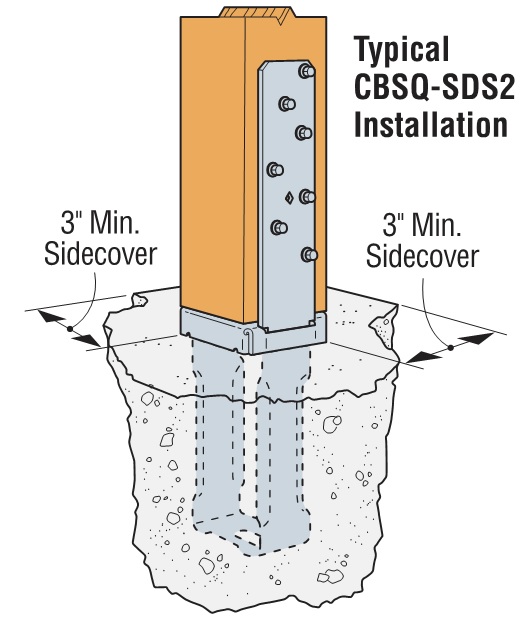

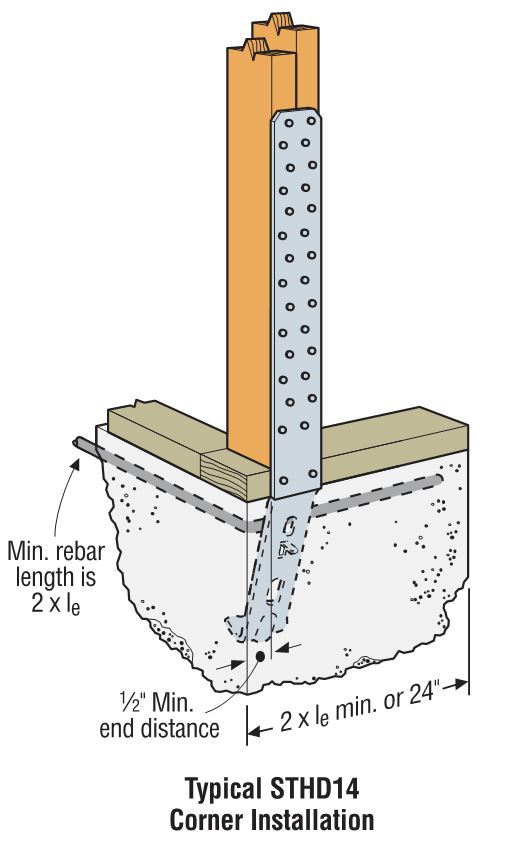

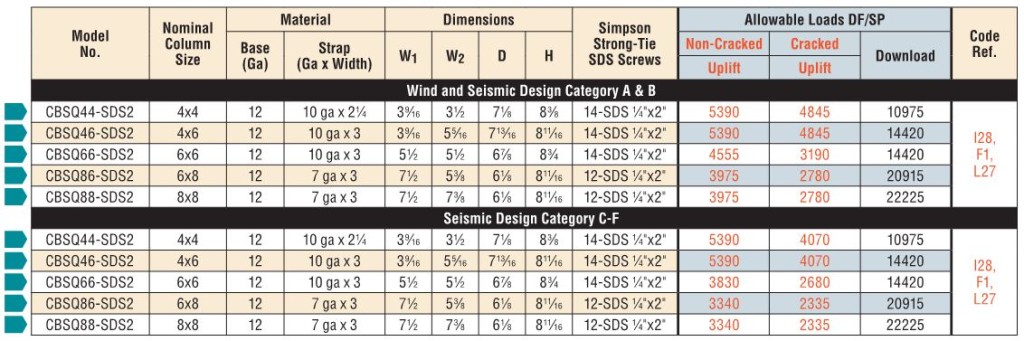

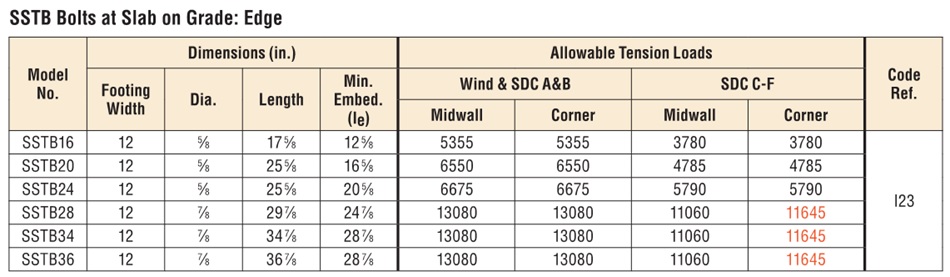

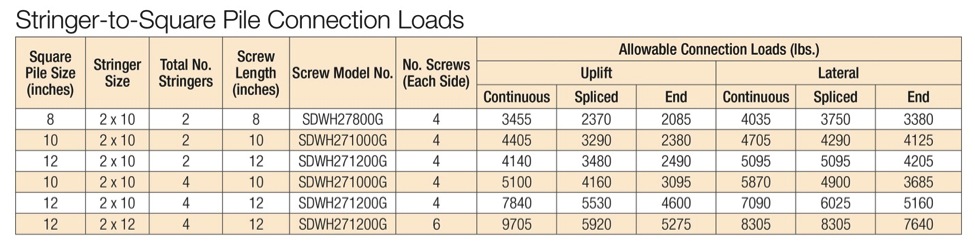

We have tested many Simpson Strong-Tie® Strong-Drive® fasteners for ledger applications including the SDWS Timber screw (SDWS22DB), SDWH Timber-Hex SS screw (SDWH-SS), SDWH Timber-Hex screw (SDWH19DB), and SDS Heavy-Duty Connector screw (SDS). We also have information regarding ledgers attached to studs and ledgers fastened over gypsum board. You can find all of this information in our latest fastener catalog.

One final construction tip – deck ledgers can fail due to cross-grain tension. This occurs when the joist hangers are attached to the deck ledger near the bottom of the ledger, but the fasteners holding the ledger to the building are near the top of the ledger. To prevent cross-grain tension failure, place the joist hangers so at least half of the ledger fasteners are below the joist hanger line.

Take a look through the various ledger options in our fastener catalog, and if we don’t address your condition, let us know. As always, call us in the Engineering Department if you have questions.

Please share your feedback in the comments area below.